Film review: Amy is a moving, sober tribute to a tragic genius

Cert 15 | ★★★★☆

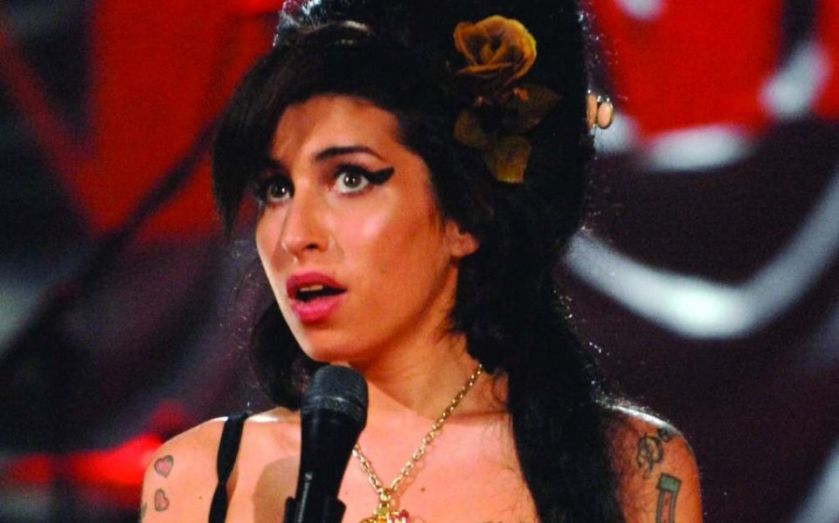

“Amy had the most emotional connection with music of anyone I’ve ever known,” says Winehouse’s pianist Sam Beste in Asif Kapadia’s documentary, Amy. “It was like a person in her life who she loved. She would die for it.” He doesn’t need to say it, it’s clear from the very first grainy clips we see, of teenage Amy strumming on the guitar.

Kapadia’s film isn’t mere tragedy or record of decline; it’s a fascinating portrait of the artist, and a convincing argument for her genius. It reminds us that Amy was special, not because of what she did, or what happened to her, but because of how she thought, wrote, spoke and, of course, sang.

Using mainly archive footage filmed on phones and camcorder (her first manager enjoyed filming stuff for fun), Kapadia charts her giddy early days as a signed musician and the grim whirlwind that followed. As with his Senna (2011), no talking heads interrupt the footage. Instead, recorded interviews with friends, family and musicians play over the top, providing ghostly commentary and emotional reminiscences over the endless montage. The only on-screen distraction comes in the form of handwritten words, lyrics from her songs that, paired with the events that inspired them, are shown to be astoundingly pithy and articulate descriptions of what she was going through.

The film takes a sinister turn when Winehouse meets Blake Fielder-Civil, the man to whom she would eventually be married. She always drank heavily and smoked cannabis, but it was after her first break up with him that she began to self-destruct. When her manager intervened and told her to go to rehab, Amy consulted her dad, who, as she later wrote in her most famous song, said she didn’t need to go.

Mitch Winehouse claims it’s an unfair portrayal, but whatever the nuances of the situation, it’s undeniable that at various pivotal moments in Amy’s life, she was let down by the people closest to her.

One of the most perceptive insights comes from her friend the rapper Mos Def, who witnessed her doing crack and says he felt she was trying to “disappear”. There’s a terrible literal truth to this: to watch the documentary is to watch her halve in size and shrink to an outline of ink, hair and bone. But the irony was that the more she tried to hide from view, the larger she loomed as a public figure. Her self-destructive tendencies were aestheticised, celebrated and, in the end, laughed at. Photographs of her in the throes of addiction juxtaposed with clips of talk-show hosts making unkind quips serve as an uncomfortable reminder that no one really cared until she was dead.

Kapadia’s Amy does what the press, her management, the public and her closest confidantes all failed to do, and that’s celebrate her for the right reasons. Despite the horror of her descent into addiction, it’s her personality and talent that shines through. Kapadia has successfully reinvigorated her legacy, not as a tragic victim of our prurient culture, but as a precious example of genius in its purest form.