Fighting for low tax rates is so 2010, now the game is in offering the best incentives

Gone are the days when countries jostled for the lowest tax rate to attract investment, now companies are looking for the best packages of incentives, and governments are delivering, writes Tim Sarson

Last autumn there was a tremendous row about the UK’s corporate tax rate being hiked to 25 per cent. Perhaps we were arguing about the wrong thing. The days when headline tax rates dominated the competition for global investment are over.

Last month I pointed out that the UK now shares a rate with almost all advanced OECD economies. The high ones have come down, the US from the heights of the upper 30s to the low to mid 20s. The low ones are coming up to 15 per cent as the global minimum tax (also known as Pillar 2) bites. Money used to flow down that tax gradient like a waterfall. Now the topography of global tax has changed. The playing field is almost level.

So is this the end of tax competition? Quite the opposite. That level playing field is ever more dotted with little undulations and a few gaping sink-holes. Countries are as hungry for foreign investment as ever. But the landscape is different. It’s all about the incentives.

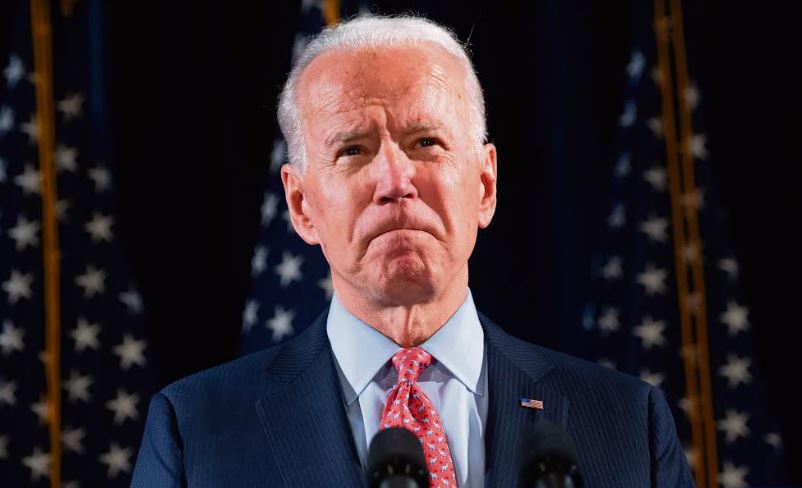

We’ve already witnessed the birth of a more protectionist US industrial strategy dressed up in the language of net zero or national security. Biden’s vast $360bn fiscal stimulus in last year’s Inflation Reduction Act specifically targets investment in renewable energy and green infrastructure. This makes the job of other countries even harder. That massive cross-Atlantic flow of investment in recent decades is in danger of drying up completely, and starting to reverse.

The EU has responded and is actively targeting green investment through its green deal industrial plan even where that means watering down some of its foundational state aid restrictions. China is already throwing tax incentives and credits at renewable energy and green investment.

As for the UK, consider three recent news stories: Labour’s plans, now scaled back but still eye-catching, to spend £28bn per year on green investment; battery maker AMTE warning it may build its new factory overseas unless we can match EU and US subsidy levels, and the latest parliamentary BEIS committee launching an inquiry into the government’s Investment Zones and Freeports. Tax rates are old hat, the action is in incentives.

The traditional low tax countries have most to lose if investment dollars get sucked back into the US. They are adapting. The way Pillar 2 works, top-up taxes only kick in if the effective rate on profits falls below 15 per cent: traditional tax rate incentives can cause this drop. But if the tax authority gives a tax credit that is refundable – paid out in cash – and accounted for above the profit before tax line like our R&D Expenditure Credit, then that is almost Pillar-2 proof. Indeed it is positively endorsed by the OECD which calls this type of relief a “Qualifying Refundable Tax Credit (QRTC)”.

We are already seeing several countries consider QRTCs. Expect further proliferation as countries replace low tax rates with more complex ways of spending the same money.

So it won’t be as easy in future to know what locations are the most tax efficient. It will depend massively on the facts. The downsides are obvious: less transparency about what’s actually being paid where; a heightened risk of government money going into pork-barrel or ideological dead ends; and further slowing of global trade and investment flows, a trend we’ve seen since the financial crisis.

But there are upsides for businesses that are on the ball. There will be money out there looking for a home. Those with dedicated incentives teams and strong policy engagement will be in a powerful position to work with government to co-invest, and secure sources of funding. When you’re investing, money upfront can be much more useful than a lower tax rate after the profits start coming in.

I’m not sure most in the tax world have clocked this big and rather recent shift, but it’s only going one way.