An extraordinary, enchanting exhibition

ART

RICHARD SERRA: DRAWINGS FOR THE COURTAULD

The Courtauld | By Joseph Funnell

Four Stars

BEST known as a small treasure-trove of impressionist/ post-impressionist masterpieces, there is something a little extra-ordinary going on at the Courtauld Gallery.

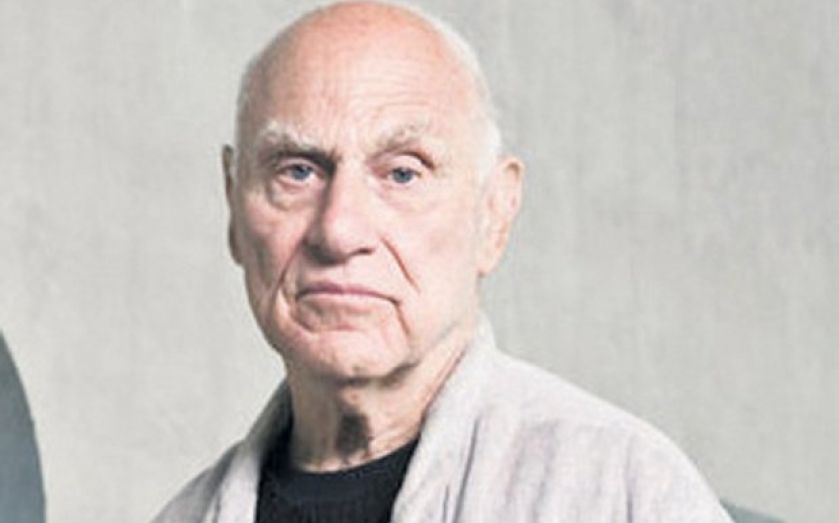

Atop its spiralling staircase we are confronted with an enigmatic set of forms that comprise a new body of work from American minimalist sculptor Richard Serra. Famous for his colossal, steel sculptures – you can find one (Fulcrum 1987) tucked just behind Liverpool Street Station – Serra has rarely shown in UK museums.

So: why? These works were born out of long fascination with the revolutionary character of a prized piece in the Courtauld collection, Cezanne’s Still Life with Plaster Cupid (c1894), of which Serra said: “You realise that someone has extended their vision in such a way that if you are going to make any contribution at all, you have to break new ground”.

Bringing in elements of his print-making practice, Serra’s transparencies really do “break ground” to the extent that we question whether they are really drawings at all. They were created through a process of inscribing on top of a multi-layered sandwich with alternate layers of melted black litho-crayon and plastic sheets called Mylar. His results come from extracting the middle layer, where double-sided impressions of encrusted black-mass hang as evidence of his “blind” process. Exquisite combinations of transparency and shadow, gloss and matt, relief and recession emerge as we literally look through these drawings and the suspended sense of space they frame. By removing the very ground on which drawings are made, Serra has interrogated the relationship between form and background to a point of perpetual uncertainty. The results are nothing short of cosmic: they offer up dark-matter explosions, spiralling forms and infinite voids, the beginning and end of the universe neatly boxed in white modernist frames.

It is a response to the space and an ethos of what the Courtauld really does: tell the history of art as a story of formal innovation and this temporary addition seems to complete a vast historical circle. Occupying a room steeped in artistic history (formerly the ante-room of the Royal Academy’s great hall), their slightly sinister presence makes you feel as if you have interrupted some kind of impromptu séance. But give them time and these willful experiments may just enchant you with their black magic spell.