Explainer: Why has the UK intervened in Nvidia’s $40bn Arm merger?

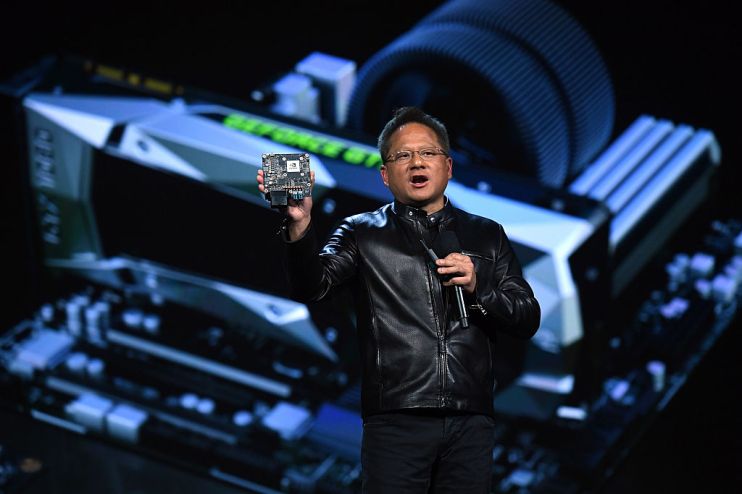

Ever since it was announced in September last year, Nvidia’s proposed $40bn (£30bn) takeover of British chipmaker Arm has proved controversial.

Critics including rival tech firms and former Arm executives were quick to hit out at the deal, warning of a negative impact for Britain and the semiconductor industry more widely.

Yesterday the government made a rare intervention, ordering an investigation into the planned tie-up. But what are the concerns and what does it mean for the UK’s M&A market?

Antitrust troubles

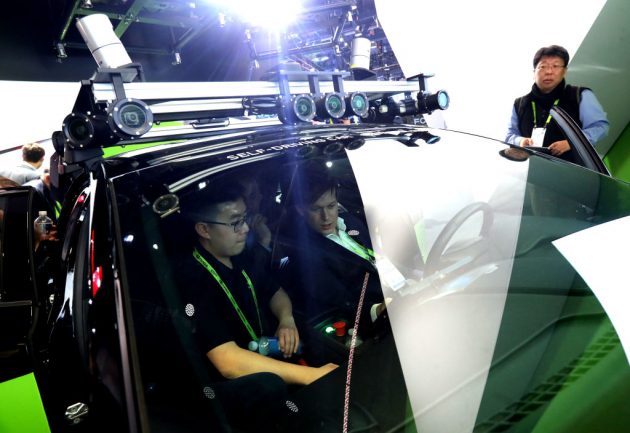

The first criticism of the bumper merger comes down to competition concerns. Arm does not make chips, but rather designs them and licences the technology to companies including Intel and Nvidia itself. These chips have a wide range of uses, from mobile phones to self-driving cars.

Opponents of the ideal argue that the merger could allow Nvidia to limit — or even block entirely — its rivals’ access to Arm’s technology.

Earlier this year the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) said it would look into the deal. Meanwhile, Google, Microsoft and Qualcomm are all said to have filed complaints, and the Federal Trade Commission is probing the merger in the US.

Nvidia has pledged to retain Arm’s neutral licensing model, but analysts remain sceptical about whether the deal should be allowed to proceed.

“In our view, the move will compromise Arm’s long-term independence, despite Nvidia’s best intentions, as the need to deliver a return on its investment creates pressure to use Arm technology in competition with licensees,” says Geoff Blaber at CCS Insight.

He adds that the deal is complicated by the wide range of different licencees in different sectors that rely on Arm’s technology, arguing that Nvidia will not be able to satisfy all their varying needs.

“We remain concerned that Nvidia’s broad business interests in artificial intelligence, automotive, edge computing and the Internet of things will inevitably clash with those of a host of companies seeking to compete with Arm technology.”

National security

However, competition is not the only concern. The proposed merger has also sparked fears of a threat to national security.

Lord Peter Mandelson last year accused the government of “waving the Union Jack while selling off the crown jewels”. The former business secretary told City A.M. that the acquisition was a “direct threat to our security of supply and sovereignty in the UK and Europe”.

The government appears to have heeded these warnings, and yesterday issued a Public Interest Intervention Notice (PIIN), instructing the CMA to ramp up its probe as part of a wider review of national security concerns.

The move is the first high-profile example of expanded government powers to intervene and block attempts by foreign companies to buy up British firms. Under the National Security and Investment Bill, which was unveiled in November, ministers will have greater opportunity to scrutinise deals in 17 key strategic sectors, including defence and tech.

This new, more protectionist approach explains why the UK is now concerned about a US buyer, even though Arm is currently owned by Japanese conglomerate Softbank.

But it also reflects the growing significance of semiconductors in the global market due to the development of new technologies such as artificial intelligence and edge computing. A global shortage sparked by the outbreak of the pandemic has only highlighted the importance of this technology.

With the majority of chipmakers found in Asia and the US, the government is likely to consider the importance of retaining a major British chipmaker.

For its part, Nvidia has pledged to keep the Arm in the UK and increase its investment in Britain. However, it is yet to sign up to any targets on Arm’s headcount. In a statement this week it said: “We do not believe that this transaction poses any material national security issues.”

Merger madness

A further implication of the government’s intervention, and its more cautious approach to national security more widely, could be a decline in inward investment.

While the UK is keen to protect its companies from hostile states — an issue that came to the fore with the row over Huawei — it must also consider the economic impact of shutting out international investment, especially after Brexit and the pandemic.

Cornelia Andersson, head of M&A and capital raising at Refinitiv, says: “With lengthy delays or even a block now facing the Arm deal, we could see increased government action unfortunately becoming a deterrent for UK acquisitions.

“These delays will be costly for M&A activity in the UK and may add more pressure as the country attempts to recover from this economic downturn.”