Explainer: Rishi Sunak’s fight against the fraudsters robbing Britain

Fraud is now the most common crime in Britain. Whether it’s done via call, text or online, it constitutes 41 per cent of all offences committed. We used to think fraud was a danger purely for older and vulnerable people, until we all started falling for it. Criminals have become so skilled at impersonating banks, telephone companies and other businesses that now even techy under-30s lose money through scams.

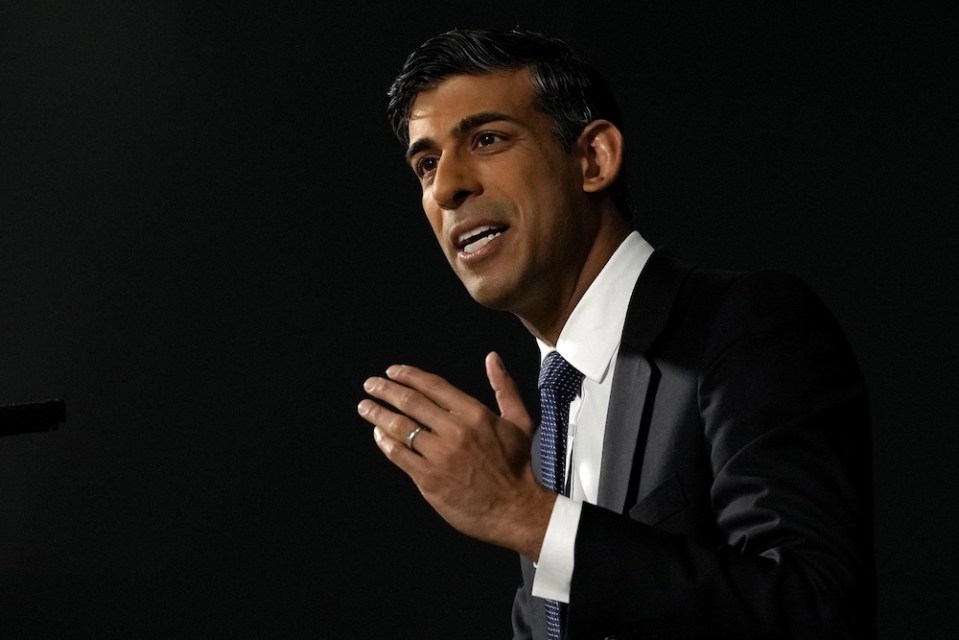

So Rishi Sunak has decided to take the fight to the fraudsters, with a new strategy that should, we are told, ensure we are protected and better equipped to deal with a scam when we see one. The prime minister is banning so-called “SIM farms”, devices used by fraudsters to send innumerable scam messages in a second. He’s also investing more energy into stopping “spoof calls”. These calls, where fraudsters pretend they’re your bank, are becoming more and more common. When I went to my bank to report one, I was told I was the fifteenth person who came to report the scam in just days.

As always when the government announces a strategy on something, there’s an op-ed in the papers and fancy words like a “new National Fraud Squad”. That means, finally, specialised investigators targeting fraudsters, which hopefully will mean the number of fraud cases actually prosecuted by the police will go up.

But what’s even more interesting is what Sunak says – or doesn’t say – about online platforms and the shared responsibility they carry when they become an avenue for fraud. “We’re going further to make sure social media platforms remove more fraudulent content, such as fake celebrity endorsement, through the Online Safety Bill”, Sunak wrote in the Daily Mail. But how much further?

Ministers were considering, for a while, making social media giants responsible for compensating victims of fraud. That would have been huge – completely overturning the idea that platforms are not responsible for malicious or dangerous content until they’re aware of it. Then the plans got diluted and the government now seems to have chosen the framework of a “voluntary agreement” with the platforms.

The controversial Online Safety Bill – once and if it sees the light of the day – will indeed introduce a “duty of care”. Big platforms will have, in some capacity, to protect their users from fraud. Not much else is known – but presumably victims will still have to go to their banks to try and get compensation.

Whatever you think of social media and Big Tech, the measures originally considered by the government seemed to fall into the burning temptation of blaming everything on Meta and Twitter. While platforms should definitely be more proactive and attentive to fraud and scams taking place in their chat rooms and online spaces, is it their responsibility to ensure fraud doesn’t take place at all? Even if it was, is it possible to police the internet so thoroughly? Or is it the government’s responsibility to equip its citizens with the tools to understand what fraud is and where it comes from, with the help of financial institutions?

None of these questions has an easy answer. The government has, at last, recognised the scale of the issue – but defeating a hydra with so many heads will be easier said than done.