Executive pay: Why I long for the restrained days of Cedric the Pig

Executive pay is back in the news. The Goldman Sachs pay pot of $12.7bn (£8.3bn) has been prominent. German executive pay has overtaken that in the UK for the first time. Top management seems to have no shame. They get some bad publicity today, but the fat cheque remains safely in the bank.

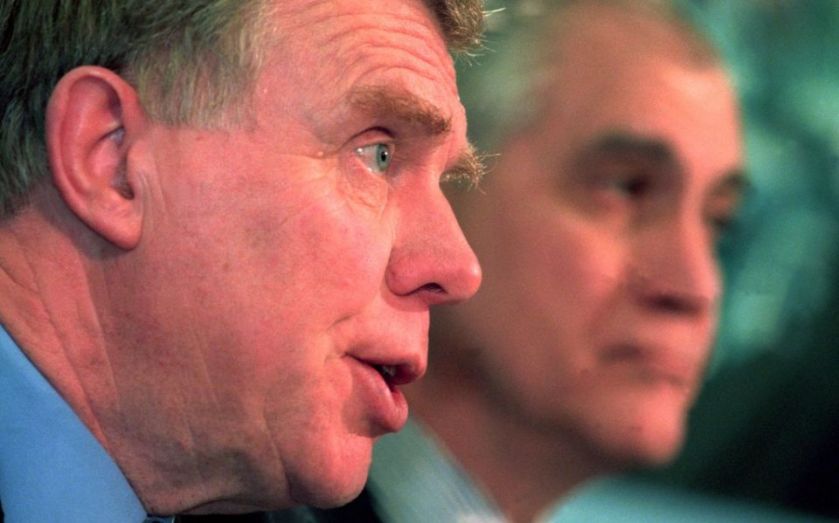

How one longs for the days of Cedric the Pig! This was the unfortunate nickname bestowed upon Cedric Brown, the one-time chief executive of British Gas whose salary was increased by 75 per cent to £475,000 at the end of 1994, at a time when the company was making staff redundant. This works out at just over £700,000 at today’s prices.

We can usefully contrast this with the remuneration package of Iain Conn, the newly-installed chief executive of Centrica, parent company of British Gas. We read on the Centrica website that his basic salary is £925,000. Well, perhaps not an indecent amount more than poor Cedric, but the text goes on to say that “to provide continuity of incentive opportunity prior to new arrangements being established two transitional awards will be made”. This means he could be in line for share awards of up to three times his base salary, plus pension contributions and “other benefits”.

Compared to many leading companies nowadays, the remuneration committee of Centrica has acted with a certain amount of restraint. Last year, the average FTSE chief executive was paid 143 times the salary of their average workers.

Perhaps economic theory can be used to justify these payments? An essential component of any basic course in economic principles is the so-called marginal productivity theory of wages. “Marginal” here does not have its everyday meaning in English, but is a piece of scientific jargon. It means the additional value contributed to the firm by a particular worker. According to the theory, the massive increases in executive remuneration over the past two decades are entirely justified. People are paid what they are worth. Certainly, this sentiment is prominent in corporate pay justifications. World class individuals are needed since they can deliver world class performances.

There are many practical criticisms of this description of how pay is determined. Yet even within the abstract confines of economic theory itself, it cannot be justified. Economics has no theory with which to explain the distribution of income. This result, which required many pages of maths to prove, was established as long ago as the early 1970s. The lineage is impeccable. Gerard Debreu received the Nobel Prize for his work on equilibrium theory, and Hugo Sonnenschein went on to become president of the free market-oriented University of Chicago. But only high level graduate students, once they have been thoroughly socialised as economists, are taught these theorems.

The simple fact is that executive pay is almost entirely determined by social values and norms. The sense of restraint, of noblesse oblige, which characterised much of Britain’s post-war history, has vanished. Until top management learns to behave respectably again, the problem will remain.

Paul Ormerod is an economist at Volterra Partners, a visiting professor at the UCL Centre for Decision Making Uncertainty, and author of Why Most Things Fail: Evolution, Extinction and Economics.