Exclusive: New Ofgem regulations risk stifling innovation, warns So Energy

Financial stress tests, fit and proper person rules, quarterly price caps…

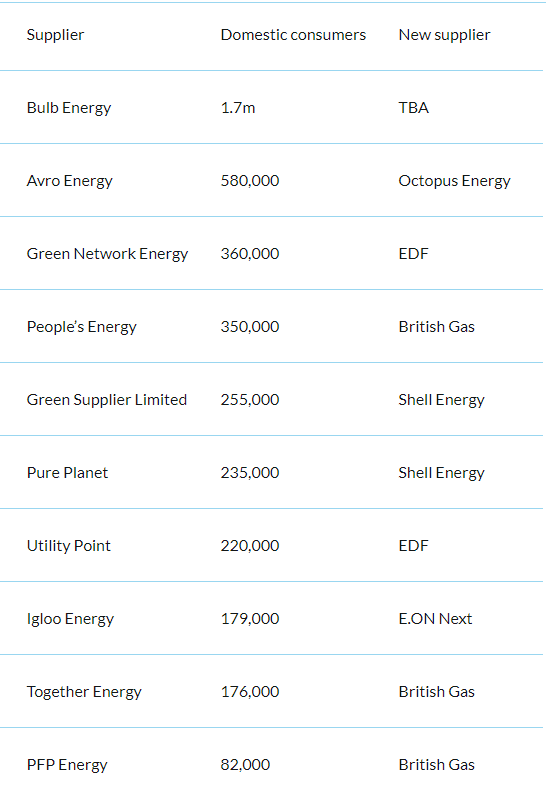

Ofgem’s efforts to reform the energy sector have gathered pace in recent weeks, following historic volatility across the retail market that has led to the collapse of nearly 30 suppliers in the past nine months – directly affecting over four million customers.

Amid the watchdog’s flurry of activity, the future of the industry is starting to take shape ahead of a challenging winter.

From now on, there will be more scrutiny on suppliers entering the market – with Ofgem demanding robust finances, competent management and healthy levels of hedging.

This is to ensure energy firms are resilient to future market shocks.

Cultural change is also on the cards, with less emphasis on switching and special deals to lure customers, alongside consumer protections such as limits on direct debit overpayments.

Much of this has been welcomed by So Energy’s co-founder Simon Oscroft, who recognised the market had been plagued with “unsustainable practices” which needed to “change for the good of customers and suppliers.”

In particular, he praised Ofgem’s temporary ban on acquisition-only tariffs – which prevent suppliers offering a deal to a new customer without also offering it to its existing loyal base.

Oscroft told City A.M.: “If your supplier offers you a tariff, but they are offering a cheaper tariff on a price comparison website and you don’t see it – then you have no trust in your supplier and it feels unfair. That just needs to go. It’s a basic hygiene factor that we should have in our sector.

However, he is also wary of the general pace of Ofgem’s reforms, concerned that some of the policies pursued by the watchdog could embolden the biggest firms in the industry with too much power and prevent new propositions from entering the market.

New suppliers could struggle to rise after reforms

For instance, Oscroft warned that demands for energy firms to ringfence customer balances will require suppliers to leave large amounts of capital aside.

This prevent funds being used to improve or bolster the offering for consumers, with money languishing in a separate account.

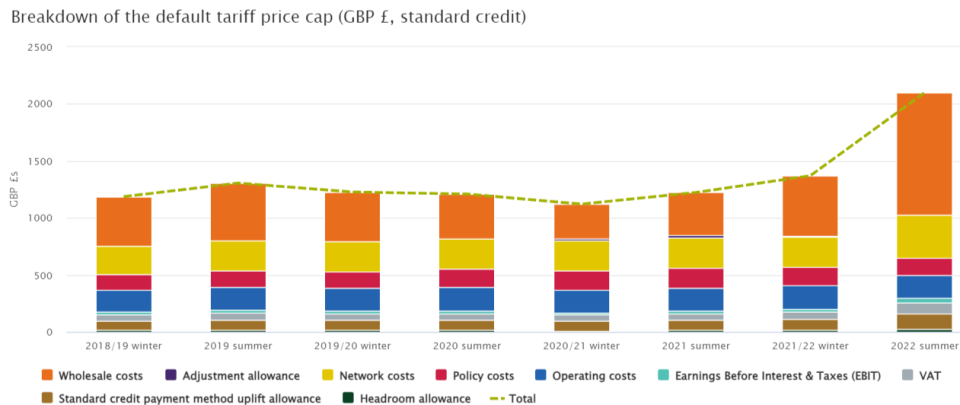

Oscroft believed this could hamper the operations of newer energy firms, forcing them to charge more, and drive-up household bills – an unattractive prospect amid price cap estimates of £3,000 per year next January.

He said: “This has a big cost that will end up on customer bills. It will also prevent newer suppliers entering the market, as they will have to raise a lot more money – and a lot of that money will sit there and just be dead capital on the side.”

Ringfencing refers to proposals from Ofgem for energy firms to protect customer credit balances, so that the money is both set aside from commercial operations, and can be returned to households if a supplier goes bust.

Ofgem wants at least 30 per cent of customer credit balances to be ringfenced, while Centrica is pushing for this to be ramped up to 100 per cent, despite rival firm Octopus Energy opposing ringfencing entirely.

So Energy’s co-founder suggested Ofgem is overcompensating for its “slow reaction” to the crisis, and argued there was a risk of “overkill” – by correcting the market in a way that favoured established firms.

He said: “I struggle to see how a new supplier could come in unless they have an extreme amount of funding and a huge parent above it. So, we will see less innovation as a result of many of these changes.”

Oscroft also believed market stabilisation charges could create a sense of injustice among energy users when conditions eventually ease.

Stabilisation charges are the costs that now have to be paid by suppliers if they poach customers from another firm, the compensate them for the hedged energy the original supplier spent on supporting the customer.

He noted this meant energy firms “won’t be able to pass on the full savings to the customers” when prices begin to drop.

He said: “That will be a real concern when it happens because I think customers will have a perception of unfairness.”

Backing customers wanting to make a difference

So Energy was founded in 2015 by Oscroft and Charlie Davies, with a focus on offering 100 per cent renewable energy at an affordable price.

The firm has grown to support over 300,000 customers, and last year merged with Irish power giant ESB Energy.

It was created in an energy market defined by boosting competition – with an emphasis on breaking up the stranglehold of the then-Big Six.

In a new era defined by tougher regulatory oversight with fewer firms, Oscroft believed surviving challenger suppliers with a distinct pitch could be a valuable alternative to the established players.

He said: “Giving customers real propositions so they can say, ‘Hey, I want to make a difference, and I want to do it with a supplier that I can trust’ – I think it is a genuine alternative.”

Oscroft recognised the vast energy market – which peaked with 80 suppliers in 2018 – created confusion for customers, but he was not in favour of a reversion to the Big Six, which dominated the industry prior to liberalising reforms in the 2010s.

“I don’t think anyone wants that apart from maybe those suppliers themselves,” he concluded.