“Equity” or “Debt”? Standard-setters must draw a clear line

The concepts of “debt” and “equity” are as old as human conversation. The concepts are not only used in business dealings but also are very much part and parcel of our day-to-day musings, for example, the question “Can I borrow your book?” or the phrase “I loved the gift you gave me on my birthday!” both touch on these same concepts.

Borrowing a book is a debt: the borrower has to return it to the lender in the same condition and form at some point in time. Making a request to borrow also confirms that the lender is the owner of the book and has an implicit right to ask for it back. Similarly, a gift is an equity: the giver passes ownership to the recipient with no strings attached.

The latter is not quite literally the case, however, as the giver could have an expectation of receiving a gift in the future. Even this premise is not entirely true. Consider who is giving the gift: is it parents or friends? In this scenario, the premise could be generally but not entirely true for all parents and friends.

It is easy to see that this concept quickly becomes complex and difficult to follow.

Investors should be provided with sufficient and consistent contractual information to make their own call: what is “debt” and what is “equity”?

Disclosure to withstand the test of time

Let’s keep it simple: borrowing a book is a debt because the borrower has to return it, and receiving a gift is an equity because there is no implicit or explicit requirement to return it. As long as the information is clearly and consistently disclosed, a person can make an individual judgment based on his or her specific circumstances. This is precisely what we do in normal conversations without getting into too many complexities.

Accounting standards have pretty much ended in a similar paradox. The IASB’s Discussion Paper , which closed for comments on 7 January, requested stakeholders to provide feedback to resolve this lingering issue between “what is debt” and “what is equity”? Historically, no major problems existed with the classification criteria, but following the financial crisis, issues have been raised around particular instruments with characteristics of equity – both from preparers’ and users’ perspectives. Therefore, the IASB is focusing on such financial instruments only; however, we believe the issue is conceptual in nature and affects other standards as well.

Unlike the simple example about day-to-day conversation, the issue at hand generally – and specifically for financial statements – is complex and requires a strong conceptual solution. We firmly believe that the process to resolve it should be similar to that taken in the previous example – that is, a clear, simple, and solid conceptual principle that can be applied universally. If the standard-setters resolutely pursues this course, we believe it could have a permanent fix that would benefit all stakeholders. In contrast, any weak, vague, and loose articulation of the conceptual principle – solely to reach a similar outcome to maintain status quo – will not be in the interest of standard-setters or benefit the ultimate users and policy makers.

Global debt, financial statements

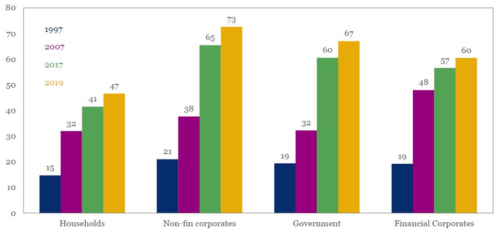

Since the financial crisis, central banks’ assets purchases (i.e., quantitative easing) have fueled a global debt bonanza (figure 1). It is likely that the following numbers for corporate debt are understated.

Source: IIF, Global Debt Monitor August 2019.

From a micro level, the changing regulatory, tax, and accounting landscape following the financial crisis has spurred a new level of financial innovation. This financial innovation is exploiting loopholes in accounting and resulting in inconsistent information for users. The main problem stems from a lack of conceptual principles and absence of transparency on a consistent basis. This is not just a problem in accounting literature but also stems from competing investor philosophies and analytical methodologies. Therefore, the discussion goes nowhere, and the only consensus emerging from it is to revert to status quo.

We understand that any significant change to accounting in this area could trigger unintended consequences (like redemption requests stemming from a change in accounting classification criteria or negatively affecting regulatory ratios) for the capital markets. Therefore, we have advocated starting with an independent disclosure without referring to the current accounting literature or changing the accounting treatment currently applied in practice.

CFA Institute policy position to enhance transparency

In our comment letter, we recommended a strong conceptual principle based on a narrow definition of equity and initiation of an independent disclosure project with an expanded scope on a priority basis. We have avoided “debt” because this term carries a lot of baggage and could lead to people using the same term but referring to different meanings or applying different interpretations.

We define equity as “the lowest ranking group that collectively becomes entitled to distribution at the same point in time. And, an entity neither has an obligation nor an option to transfer economic resources to such a group.”

Therefore, any item (i.e., liability, instrument, provision, approval of share buybacks mandate, or any other kind of obligation, including by law, regulation, or contract) failing to meet – or until it does meet – this definition would be included as “claims.”

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to Market Integrity Insights.