We’re ignoring a basic tool to help the poorest with their energy bills right now

In the throes of an inflation induced cost of living crisis, energy prices need urgent political and policy attention. The plans put forward tend to vary around traditional conceptions of more tax, less tax or price suppression – but there are also ways the government can do highly targeted interventions to people in need.

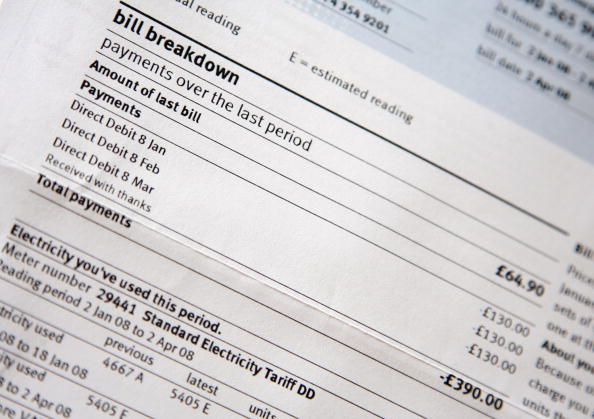

Targeted cash relief is often posited as a more equitable solution because it directs taxpayers’ money to those most in need over those that would probably be fine without any help. And to be fair to the government, they have been giving people cash where possible, but the point is how best this can be executed and how we build an infrastructure that allows them to do this quickly in a crisis – like right now.

There are two fundamental questions in delivering targeted interventions like this. There is the philosophical question of who is most deserving of help, and the logistical question of how to actually deliver it. And answering these questions is a lot easier with more and better use of one crucial asset – data. It is true that ‘data’ as a term can be so overused, (“data is the new oil”) that it’s easy to dismiss it as hype rather than see it as a genuinely useful tool at the government’s disposal.

But look to Portugal, who delivered their Social Energy Tariff to people proactively (i.e. without them having to sign up for it or even know it exists). Upon realising that people who should have benefitted from the tariff were not registering for it, they automated the process. Portugal managed to corral the data from both the public and private sector – the energy companies, the tax system and the social security system. And so the number of households receiving the tariff then increased from 154,648 to 726,795, seamlessly providing financial support to 7 per cent of the Portuguese population for the cost of their energy.

The proactive element of Portugal’s policy – enabled by data – is important, because the fact that people have to actively know about policies to ensure they get it can hinder take-up, limiting financial support. The closest equivalent to this in the UK, the Warm Homes Discount Scheme, requires people to reach out to their supplier to find out if they’re eligible, and then apply online.

In further contrast to Portugal, not only does a lack of useful data limit how much support people actually receive, but it can also create botched and unnecessarily complex policies. The council tax rebate announced in February to assist with energy bills relies on property values from 1991, and if your house was built after 1991, a 1991 valuation is created and used to determine the council tax bands. Even then, everyone within the eligible bands gets the same amount because council tax famously does not take into account the inhabitant’s income.

With all of this said, it may be that targeted interventions are not always the way forward. They come with more questions than just how to deliver – who should receive the money, how much money, how it is paid for, how long this support will last. And it does not help solve the long term question of how we transition to renewable energy sources.

The notion that plausible policy ideas could be dismissed not because they might be the wrong choice, but because it would simply be impossible to calculate or deliver properly, when the government does have the data, is absurd.

For many policies, the necessary data does exist, but it is spread all over government – one department might have your date of birth, another your income, and so on. So trying to bring together disparate databases for any sort of policy design or delivery can be a gruelling task. And where this can be overcome, there is then the obstacle of outdated code and data architecture that nobody understands because it was built in the 1970s.

Streamlining databases across public services is such an obvious win for any government to instantly improve the quality of policies they produce, especially in a crisis. And politically, being able to put cash into the right people’s pockets delivers tangible public value quickly and easily.

But a chronic lack of prioritisation and under investment in data infrastructure makes Portugal’s Social Energy Tariff seem like a distant dream. It’s not that the government cannot deliver more targeted, more proactive services, it’s that they don’t.