Elizabeth II was Britain’s monarch, but she held together our bonds to America

In politics and foreign policy, the personal counts for far more than those cloistered away in ivory towers of theory and philosophy can understand. It is not just grand historical forces that make the world what it is; specific people—with all their strengths and weaknesses—make history.

Elizabeth II, whose long life and reign have just come to an end, exemplified this reality, particularly regarding her role in keeping the special relationship between the UK and the US afloat.

Yes, in impersonal grand historical forces terms, the two nations have a lot in common that binds them together. Economically they are among each other’s greatest foreign direct investors. Like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid they always seem to come out shooting together on the same side, as in the three primary geopolitical contests of the 20th century: World Wars I and II, and the Cold War.

They also ideologically epitomize a particular brand of democratic freedom (long on personal liberty) and a more dynamic, unfettered brand of laissez-faire capitalism than their European counterparts are comfortable with. And, of course they both speak English, which means diplomatically they gravitate together.

All of these amount to the ties that bind, but the special relationship did not just come about as an inevitability of these grand historical forces. Rather, real people, from Churchill to Roosevelt, from Eisenhower to Macmillan, from Reagan to Thatcher, toiled in the diplomatic vineyard to make the crucial link work. And there in the midst of it all, we find Elizabeth II.

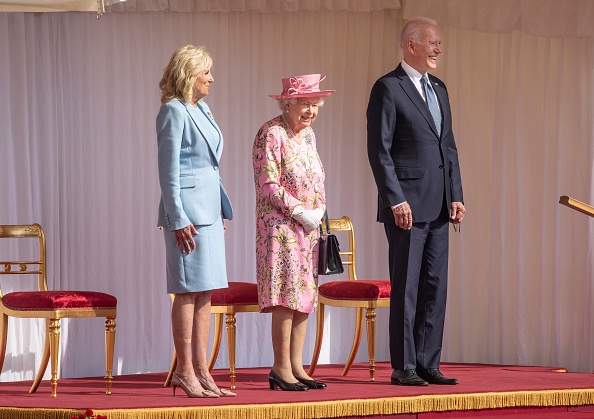

In what must be some sort of a record, the Queen met 13 presidents, from Harry Truman, who she met as a princess, to the present occupant of the White House, Joe Biden. During her reign, she failed to meet only Lyndon Johnson during her 70 years on the throne, though they did correspond. This institutional memory, spanning the seemingly endless era from the 1950s to the 2020s, was invaluable as the Queen personally and practically knew more about America’s presidential lineage than many occupants of the Oval Office.

Said to be among her favorites were Dwight David Eisenhower (who she had met as a girl when he was running the war effort, and with whom she shared her recipe for scones), Ronald Reagan (with whom she shared an easy charm and a common love of horses), and Barack Obama, who said she reminded him of his no-nonsense grandmother.

There were, inevitably, various protocol gaffes along the way. Jimmy Carter committed a rather serious faux pas by kissing the then Queen Mother on the lips, rather than bowing. Waspishly she replied, “Nobody has done that since my husband died.” Michelle Obama touched the Queen’s shoulder, though the Queen didn’t seem to mind as much as the British tabloids did, and George W. Bush playfully intimated that the Queen had been present at the founding of Jamestown in 1607, which she seemed to find funny.

Through it all, the endless state dinners with 13 sitting presidents, the Queen symbolized the strength and durability of the special relationship, paradoxically understanding that—as is often true of convinced believers in Republican government—most of the leaders she met were suckers for the majesty of the monarchy.

Perhaps this fairy dust was nowhere more important than during her first state visit to Washington in 1957, just after the Suez crisis had deeply damaged cross-Atlantic bonds, with its future into question. The Queen got on easily and well with Eisenhower, who—after years of working cheek-by-jowl with the British in World War II—was also anxious to contain the damage. The diplomatic success of the trip symbolized that despite real differences over the winding up of the British Empire, the special relationship could endure, when well tended.

Like most adroit diplomats, Elizabeth II made it all look so easy. But of course, it wasn’t. She understood and executed an elusive notion: the personal remains political. She should be honoured in her passing for many things, not least of which her central involvement in keeping the vital special relationship on the road.