Election 2015: What it could mean for financial markets

Traders shouldn’t fear an inconclusive result, argues Luis Eduardo Barrueto

WITH just 71 days until the General Election, companies have already started to prepare for political uncertainty and negative developments in policy. Rothschild, the UK investment bank, is reported to be considering handing out its 2014 bonuses to staff in May, a month earlier than usual, to avoid a potential windfall tax announced by Labour.

But such contingency planning is all the harder in the run-up to this year’s vote because the result itself is so uncertain. While a poll by Opinium this weekend gave the Conservative Party its first lead for that company since 2012 (with the Tories at 35 per cent and Labour at 33 per cent), others have pointed in the opposite direction. And while betting companies suggest that the Conservatives will win the largest number of seats, very few analysts are predicting any sort of overall majority in May. According to polling expert professor John Curtice, it will be nothing less than a “lottery election”.

But what does this mean for markets? Traders and investors have plenty of other things to worry about in the run-up to the May vote (not least the continued risk that the Eurozone crisis will return). But both a growing distrust of markets among the public and the possibility that Britain could be governed by some unstable new coalition mean that the result of the election is not the only hard call. Its potential effects are too.

A NERVE-RACKING CHOICE

Markets tend to prefer a Conservative government in 10 Downing Street. Late last year, Panmure Gordon’s senior UK economist Simon French analysed the impact of every election since 1966 on UK markets. Over 22 years of Labour governments and 26 years of Conservative or Conservative-led governments, equity markets returned 7.3 per cent annually under Labour and 11.7 per cent under the Tories.

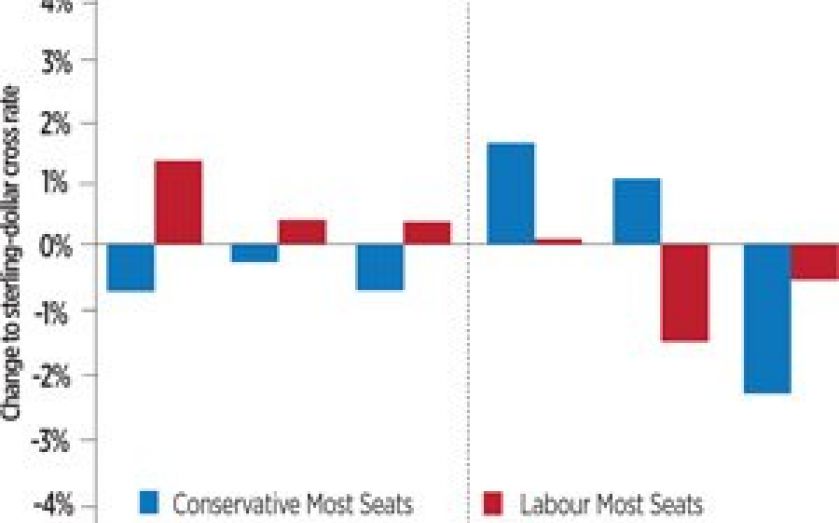

French also found this “partisan behaviour” in the run-up to elections (see chart), with stocks consistently delivering positive returns in the months leading up to votes when the Tories gained the most seats.

This works for elections with clear likely results, but what about 2015? With the major parties neck and neck, it’d be simplistic to argue that we should be expecting a major sell-off just because there is the chance of a Labour government. After all, it’s not as if it’s a secret that this election is hugely uncertain.

Instead, French posits that the closest parallel is with 1974, when that year’s February election resulted in a hung parliament and a second vote that year. Traders should be looking out for sharp moves in the polls towards the Tories or Labour. Any consistent trend towards one party or the other could have a sizeable impact on the equity markets.

STERLING AND GILTS ON TENTERHOOKS

Aside from equities, what other effects could the election have on markets?

“A Labour government could see the pound weaken and financial stocks fall in London trading as a result of the City’s dim view of Labour and its economic credentials”, says Joshua Raymond, chief market strategist at City Index. The election could also result in sharp moves in UK government bonds. “We could see additional price volatility in UK gilts, with the City seeking safe haven investments should Labour win, at least in the short term, as they digest the consequences for the UK economy”, he adds.

French, however, did not find the same partisan moves in gilts and sterling as in equity markets.

And so far, currency markets have paid less attention to politics in the UK than to the happenings across the English Channel, notably the European Central Bank’s introduction of quantitative easing and the negotiations surrounding Greece’s debt, alongside hawkish notes from the Bank of England. Sterling has reached a seven-year high against the euro, after minutes from the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee revealed that the unanimous decision to hold interest rates at 0.5 per cent was “finely balanced”.

LOOKING THROUGH THE HYSTERIA

While it has become a cliche that “markets hate instability”, and many worry that the rise of protest parties in Britain’s first past the post electoral system will forever destroy the chances of stable government, French actually thinks an inconclusive result would have “significant attractions to the City and the UK’s economic growth prospects more generally.”

As his colleague at Panmure Gordon David Buik notes, a Labour government is committed to cracking down on banks, energy suppliers, tobacco firms and pharmaceutical companies, and an overall majority for Labour would be problematic for those sectors.

But equally, as Tom Elliott of deVere Group has warned, the Conservatives’ promise of a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU has introduced “considerable uncertainty into the outlook for the economy, since Ukip and other eurosceptics are running a populist campaign that challenges the evidence of economic history of the benefits of being within a free trade area such as the EU’s single market.”

If both Labour and the Conservatives fail to achieve an overall majority, they will struggle to push these policies through. “The dangers of derailing the UK’s current good economic performance are in fact mitigated by an inconclusive result in May,” says French. “The biggest challenge would be to look through the media hysteria that would be inevitably associated with such an outcome.”