| Updated:

Eight ways technology has reinvented fiction

At a recent lecture in Oxford, Will Self announced the death of the novel. The internet, he said, has mercilessly invaded the silent, solitary leisure time we once filled with “serious” reading. As a result, serious books will no longer feature as a central part of culture. Like classical music, they will continue to exist, but only as a rarified subsection of the arts enjoyed by a small group of educationally privileged people.

Perhaps. But while the internet may be harming “serious” literature, it’s also facilitated the birth of a variety of new literary forms, many of which have encouraged reading among people who wouldn’t ordinarily have picked up a book. From cell-phone novels to eBooks to fan fiction, it’s clear that – whatever the health of the novel – storytelling is thriving. Here are eight of the new literary forms that have emerged in the age of the internet:

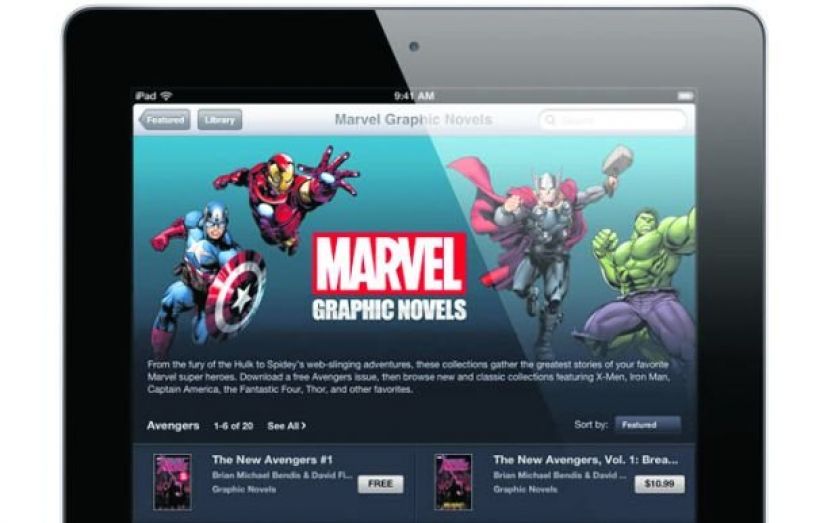

Digital Graphic Novel

The comics industry tends to be fairly progressive – geeks and technology, after all, often go hand in hand. Publishers large and small quickly cottoned on to the importance of tablets, with digital versions of most comics and graphic novels (the former being published in installments, the latter as a single text) now available. These allow users to easily flick between panels and zoom in to fully appreciate the artwork. Moreover, digital comics are taking advantage of technology in ways that written literature can’t (or at least isn’t). Many now incorporate sound effects as readers scroll from panel to panel, include short animations and provide a musical soundtrack. These elements blur the lines between literature and film, creating an entirely new genre that features elements from both but is a distinct product.

Philip Pullman has taken to Twitter like a duck to water

Twitter Literature

David Mitchell may be the first author to release a short story via Twitter, but the social networking site has been promoting itself as a home for fiction for years. High profile literary authors from Helen Fielding to Ian Rankin, from Jeffrey Archer to Philip Pullman have taken up the challenge of writing snapshots of prose in 140 characters with relish, taking to the notoriously succinct medium like wordy ducks to water. Twitter even held its first Twitter Fiction Festival in 2012 in which anyone with an account could contribute their own attempts by using the #twitterfiction. This year’s festival teamed up with Penguin Random House, the American Association of Publishers and USA Today and it promoted parody accounts and fictional handles as TwitLit in their own right.

Fifty Shades of Grey started life online

Fan Fiction

In the age where everyone and his dog has a blog, it was an inevitability that popular fiction would fall into the hands of the everyman. Fan fiction has been around for decades but only recently has it reached a mainstream audience. The best example is Fifty Shades of Grey, which started off as an online S&M spin on the Twilight novels. One canny publisher saw its potential, wrote out the character names, got rid of the fangs and created one of the most popular novels of its time. Pretty much every work of fiction now has its fan-fiction equivalent – Harry Potter is another popular target – with fanfiction.net providing the world’s biggest archive of amateur scribblings.

The cell phone novel is a precursor to TwitLit

Cell phone novel

The “cell phone novel” sounds like a joke from a dystopian satire but it’s real. A precursor to David Mitchell and Philip Pullman’s TwitLit, the novels are mostly love stories written in short sentences which are uploaded onto social media or self-publishing sites via a user’s phone. Often they’re written by people in their teens and twenties who don’t feel constrained by grammatical accuracy. Some of the most popular ones have been released as books and have attracted massive sales. Japanese bestseller lists are often dominated by them, and now, with companies such as eMobo selling English language versions, they may become a fixture of our culture, too.

Gifs and comics are a match made in heaven

Gif Comics

Gifs – compressed image files that often illustrate Buzzfeed lists – and comics are a match made in heaven. French animator Stephen Vuillemin created a hugely-popular, 10 chapter gif comic called Schoolgirls that tells the story of a Parisienne girl who loses her memory after suffering a serious ear infection. DC and Marvel fans now use the technique to animate their favourite issues and the Ruffles series, a gif comic that parodies the uber-masculine, mustachioed men of 70s action films, has over 200,000 regular followers.

Canadian Margaret Atwood has been published on Byliner

Web Serials

Rising literacy levels and advancements in printing technology popularised serialised novels in the 19th century but web serials have brought them into the 21st century. Websites dedicated to the new genre include Tuesday Serials, which publishes highlights from around the globe every week, Jukepop Serials, whose authors are vetted and paid in line with readers’ votes, and Byliner, a US-based subscription service that has attracted the likes of Margaret Atwood and Chuck Palahnuik.

Self-published eBooks are typically 10,000-35,000 words

eBooks

Normal, old fashioned books tend to be around 200-400 pages, not because this is some magical sweetspot in the communication of narrative, but because 100,000 words is just about the most convenient length for printing, transporting and selling physical copies of books. You might have written the greatest piece of fiction of all of time; if it’s 2,000 pages you’re unlikely to find a publisher who will put it out. Most self-published eBooks tend to be more in the region of 10,000-35,000 words, putting them somewhere in between novellas and short stories in a whole new category of storytelling.

App versions of books for tablets have taken off in recent years

Tablet Fiction

More a new way of consuming literature than a new form, tablet fiction accords with the “tangential mind” of the internet age. App versions of books and poems for iPad have taken off in recent years with readers attracted by extras including commentaries and interactive footnotes. The advantage of books as apps can be seen clearly in richly allusive modernist texts; apps for TS Eliot’s The Waste Land was a huge success when it was released complete with interviews with Seamus Heaney and Jeanette Winterson, as well as a selection of readings including one from Eliot himself.