‘Edtech’ surges to the top of the class

From near-ubiquitous interactive whiteboards to cloud platforms, coding and coaching via video-call, education technology has travelled a long way since schools introduced basic computing laboratories in the 1980s.

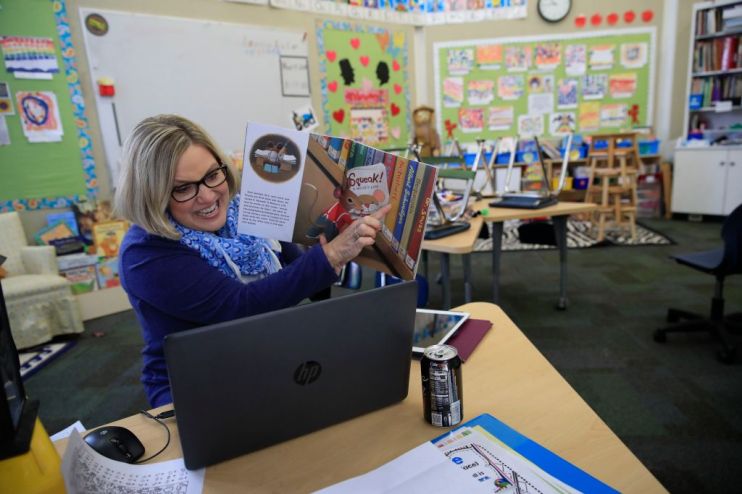

These advancements have been given a further powerful push by the digital acceleration triggered by coronavirus: most visibly in the need for teaching professionals to deliver classes remotely.

It’s an unprecedented (and very odd) new world across education: from primary schools practising social distancing right up to prestigious universities such as Cambridge committing to deliver lectures online for the next academic year.

Clearly, in unexpected and yet sometimes radical ways, the use of technology in education – ‘edtech’ – is at an all-time high.

Technology can help teachers and pupils

The Department for Education wants to “make sure no child falls behind as a result of coronavirus”. Government actions have included the £1bn coronavirus ‘catch-up fund’ for schools (announced in June); and more than £100m to help children to learn at home.

More than 200,000 laptops and tablets, plus almost 50,000 4G wireless routers, have been dispatched for disadvantaged and vulnerable children. “We are also offering free, expert technical support for schools to get set up on an accredited digital education platforms to support remote education,” a DfE spokesperson tells City AM. “Pupils will continue to benefit from these investments in the long-term, both inside and outside of the classroom.”

Also, government is supporting the Oak National Academy, an online learning platform that launched in April, and the EdTech Demonstrator Schools and Colleges Programme (launched pre-pandemic). “Technology has the potential to reduce teacher workload, enhance flexible working and improve pupil outcomes,” the spokesperson says.

It is 16 months since the government released its ‘EdTech Strategy’, acknowledging that government digital services in education “too often fall short of the world-class standards we set for ourselves and the wider technology market”.

Some of the world’s biggest companies, such as Microsoft and Google, were at the front of the class with endorsements of Whitehall’s direction of travel.

‘UK is an edtech leader’

Edtech exports were last year estimated to be worth about £170m to the UK economy, while more than 1,000 companies – from some of the world’s largest digital corporations to start-ups – are estimated to be active in the market.

Examples highlighted by the Education Foundation – which, through partnerships with companies such as Amazon Web Services and Intel, organises events and advocates on behalf of the edtech sector – include SpyQuest, an interactive game designed to inspire children to read; Sparx Maths, which combines maths content with data science and a tech platform to help with maths teaching; and now>press>play, which uses wireless headphones to enable primary children to become the main character in stories.

The British Educational Suppliers Association (BESA) represents more than 400 companies, with many offering their solutions to schools for free during lockdown to help them deliver home learning.

“The UK is an edtech leader and the recent school closures have served to highlight the importance of this growing sector,” BESA’s operations director Julia Garvey tells City AM. “The challenges of delivering home learning have shone a light on the need for students to access content remotely, and for improved infrastructure and funding to enable schools to put these systems in place.”

Even though schools are preparing to return in September, “ongoing demand for online learning is expected to fuel further growth in the edtech sector, despite the constraints of limited school budgets,” she adds.

Pandemic could shift the dial

Ty Goddard is co-founder of the Education Foundation, as well as being chair of Edtech UK, which launched five years ago to promote the edtech sector in Britain and also globally.

“Wales and Scotland have been seen as ahead of England in respect of edtech policy,” he says. “But last year’s EdTech Strategy launch should give momentum and, certainly, the way technology has needed to be used during the pandemic should accelerate interest. We could do with an EdTech Strategy refresh to take into account where we now are.”

Goddard is also part of the recently formed Edtech Advisory Forum, whose membership comprises tech specialists and school leaders. The group has just begun a review of the edtech sector, and a look its future direction, with the aim of publishing its conclusions early next year.

“The pandemic saw many ‘digitally-rich’ schools switch to become virtual schools in a matter of days but also revealed starkly the areas neglected in edtech,” Goddard says.

It adds up to a classic case of not wasting a crisis. “It is all about supporting educators to do their jobs more effectively and efficiently – not replacing them. If anything good can come out of this awful crisis it is that edtech will be taken far more seriously,” he says.