Ed Warner: Why the Olympics is frozen by complacency

Curl up for the curling. Settle down for dust-ups on the rink. Thrill at the sliders and skiers. Swoon over the skaters. Grumble about geo-politics and overbearing branding. The Olympics are here again.

Not the Olympics Olympics, obviously; rather their smaller Winter sibling. Less than half the number of competing nations, a quarter of the athletes, a third of the medals. But two thirds of the global TV viewing figures, so enough to keep both broadcasters and sponsors happy in the lull between Summer Games.

These are the two cohorts which matter for the International Olympic Committee (IOC), bringing in 91 per cent of its $1.4bn annual revenue. Some of the IOC’s surplus is distributed to the bodies providing the sports and athletes that make up its Games, but over time the owner of the Olympic rings has amassed a reserve of $2.5bn. Quite the rainy day fund.

The IOC, awash with this cash, has allowed itself to get frozen in a crevasse of complacency because it continues to find brands happy to pay to be part of the Games, and cities eager to host them. It may innovate around the digital delivery of its events for a worldwide audience, but has no apparent appetite to address their formats which increasingly look like relics of the late 20th century; over-organised, over-blown, over-long and over-hyped. And don’t get me started on torch relays and ceremonies.

As with any business that wakes up one day to find it has become irrelevant, or technology that slips into obsolescence, the Olympics risks becoming just the comfort viewing of an ageing – and so shrinking – cohort of the population. Mid-table mediocrity looms. Slipping a few new, younger sports into the Summer roster is hardly going to reverse the slide. Bolder ambitions are required for the Olympic brand.

If you doubt my mid-table claim, consider this: the English Premier League’s global broadcast revenues of around £3bn ($4bn) a year are around four times those of the IOC, having expanded at a far faster rate. Different products, but the same global market. The disparity is not down to luck.

Being an Olympian – better still, an Olympic medallist – and being able to put the initials OLY after their name continues to have huge cachet for athletes. Even the world’s golf and tennis stars are being won around as each Games comes and goes.

Sports, too, hanker after being part of the circus. Cricket doesn’t need the money, so why else is it lobbying to be included? For smaller sports like netball and squash – the latter perennially disappointed at its exclusion – the allure of visibility and so commercial opportunity is obvious.

This magnetism of the five rings is the IOC’s opportunity to take a big leap forwards, to include more sports, mint more medals, snaffle a greater share of the global broadcast and sponsorship cakes.

This could only happen if the IOC was bold enough to break the Games out of their two short bursts of sporting action within each four-year cycle. Beef up the Winter Olympics by adding a cluster of indoor sports. Add a thematic Games or two – Urban Olympics and a Combat Olympics anyone? An e-Olympics too?

Move away from the model of single-city hosts. Think nations, continents or simply the whole world as an Olympic host. A centralised Olympic Village may be fun for athletes, but is a sporting irrelevance and a barrier to more creative – and much larger scale – hosting.

In a single Olympic year, the Games could comprise a series of clustered sports in a variety of locations through the course of the 12 months. Each sport would be tasked with delivering a pinnacle event under the kite-mark of the rings. Quality would be key and could be secured if the IOC bought the rights for world championships so that they became embedded elements of the Olympics.

And if Fifa is determined to move to biennial football World Cups, why not fight fire with fire and aim for every other year to be considered a fully-fledged Olympic one? Some sports could appear each time rather than every four years. Yes, there would be a few international governing bodies who fought against that competition for their own events, but others might calculate that there was much more upside to throwing their hat in with the IOC.

Just how huge and how valuable would the global audience be for an India v Anyone, T20 cricket Olympic final at LA28?

The Olympics brand is remarkably resilient and, hard though it might be to accept, still grossly under-exploited. Think of it as a badge that could be applied to any high quality, global sporting competition, not just the current quirky collection, and suddenly the ceiling on its potential is blown off.

Norwegian would

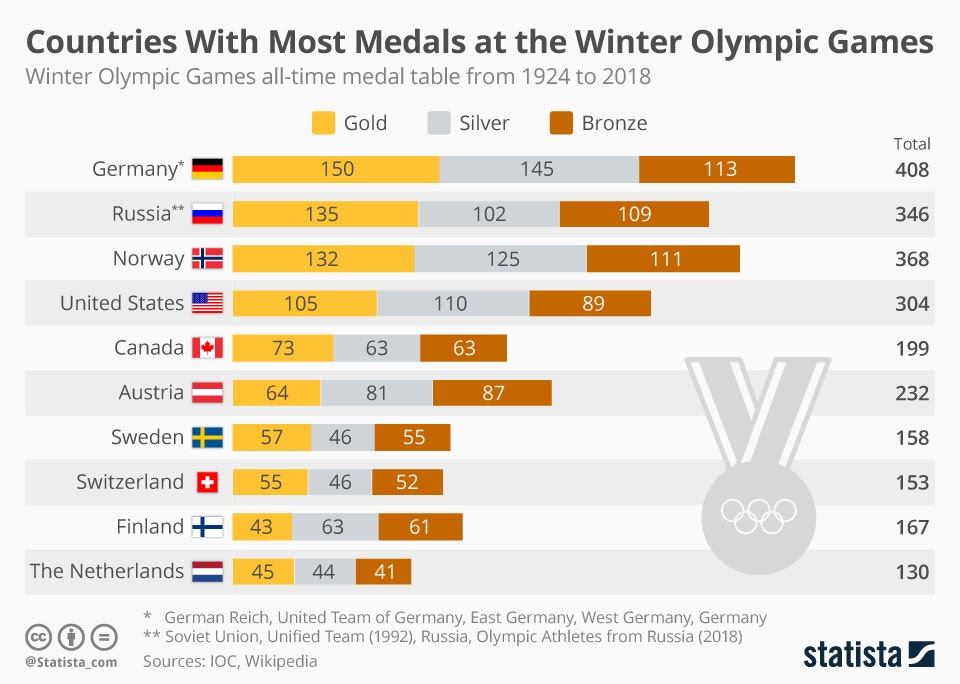

I’m indebted to a reader for sending me a fascinating article from Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper examining Norway’s sporting model, which has not only delivered more Winter Olympic medals than any other nation (although the reunified Germany may quibble) but also increasing success across a range of other sports. A top-of-the-table showing is on the cards in Beijing over the next couple of weeks.

What shines through from the analysis is a systematic approach, well funded, that gives kids a very broad grounding across sport, de-emphasising competitiveness while they are young. It helps, in snow sport terms, that the country is blessed with a lot of the stuff, and that the likes of biathlon and cross-country skiing are akin to religions for Norway’s sport-watching populace.

Away from the Winter Olympics, it will take consistent success over a number of years to prove the value of Norway’s system. I’m reminded of my early days at UK Athletics when I was urged to study and then replicate the “Swedish model”. At the time this country boasted superstar heptathlete Carolina Klüft (Olympic gold in 2004 and three world titles) and jumpers Kajsa Bergqvist, Stefan Holm and Christian Olsson.

Turns out there was no model – or certainly not a successful one – as Sweden didn’t win a single medal at the next World Championships in 2009. It seems that the planets had simply briefly aligned for them. Sweden’s current superstar, pole vaulter Mondo Duplantis, was raised in America by a pole vaulter father and heptathlete mother. Nothing replicable there.

There is little to be lost, though, in athletics’ leaders checking out Norway’s current Olympic champions, Karsten Warholm and Jakob Ingebrigtsen, in an attempt to sift the systemic from the specific for structures there that could be copied.

Ed Warner is chair of GB Wheelchair Rugby and writes at sportinc.substack.com.