Drug companies are producing more new cancer drugs than ever before – but can countries actually afford them?

The world faces a cancer medication conundrum. On the one hand, the ageing population means we need more effective treatments for the disease, but on the other hand these can cost so much to create that we can't use them.

The IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics estimates that last year, global spend on cancer drugs reached $100bn (£66m) for the first time ever, which amounts to $99 per head. This was up from $71 per head in 2010, and marks a 10.3 per cent increase in spend compared to 2013.

Why the sudden surge in spending? Pharmaceutical giants like AstraZeneca, Roche and Merck & Co are all investing in a new kind of cancer treatment that work by harnessing the body's own immune system to fight tumours.

These drugs are highly effective, and have been heralded by experts as the biggest step forward in cancer treatment in decades. “New therapeutic classes and combination therapies will change the cancer landscape over the next several years,” the US analytics firm said in its report.

But such progress comes at a price – some of those launched in the US in recent months have reached costs of around $150,000 per year, and the result is that many of them will never be used to treat patients because public health services won't be able to afford them.

Between 2010 and 2014, 45 new cancer drugs were released by pharmaceutical companies, but in no country across the world have patients had access to all of them. The broadest access was seen in the US, Germany and the UK, while very few were available in Japan, Spain and South Korea.

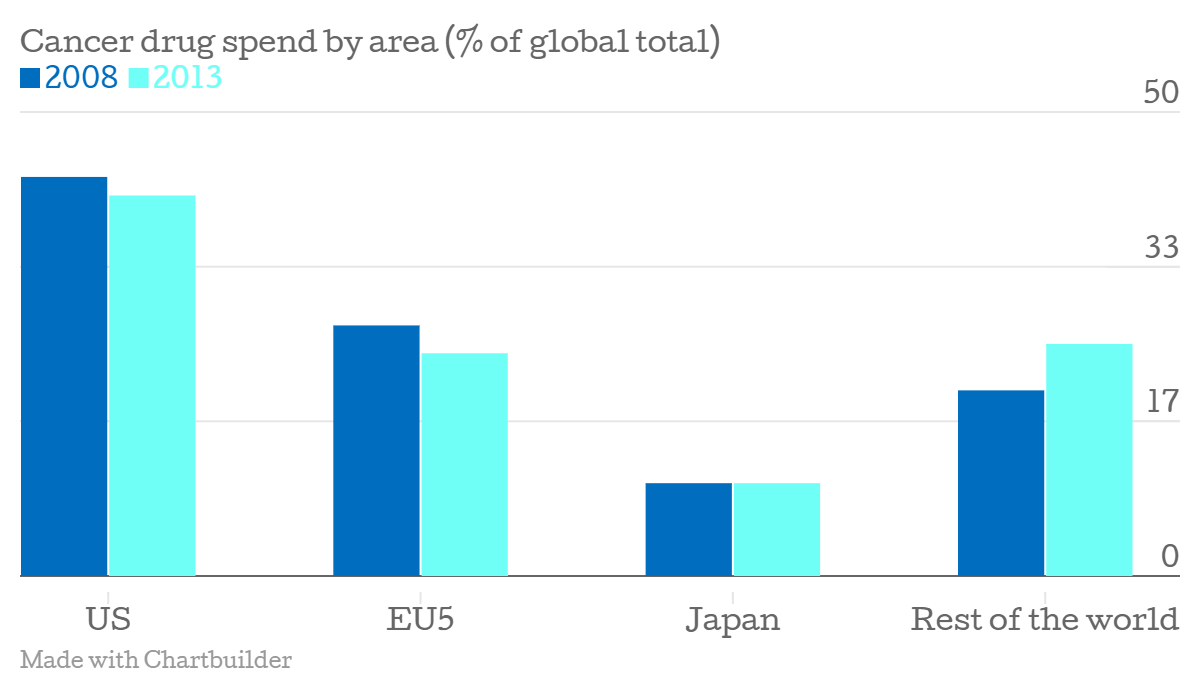

This falls in line with national spend on cancer drugs as a proportion of the global total, with the US coming first, with 42.2 per cent, followed by the five biggest economies in Europe – Germany, France, Britain, Spain and Italy (EU5).

UK losing out

In the case of the UK, a Cancer Drugs Fund has been set up to allow greater spend on treatments for the disease than would be allowed under normal NHS conditions, but it is still unable to purchase many of the new medicines that come to market.

In fact, its ability to invest in new treatments is diminishing – earlier this year, the government earmarked 16 cancer drugs for ejection from the fund, on the grounds that they were not cost-effective enough to warrant provision on the NHS.

This reflects a shifting global trend, which can be seen in the graph above – over the five-year period, the dominant forces in drug manufacture have been losing out to the rest of the world.