Don’t lose faith on UK interest rate cuts just yet

The UK has found itself in the eye of a financial storm since the turn of the year, with government debt selling off and the pound taking a beating.

Many analysts have noted that international factors – in particular changing bets on US interest rates – have been more important in driving UK market movements than domestic factors, and this is true.

Nevertheless, there are some UK specific causes and these causes help explain why the sell-off in UK assets has been (slightly) worse than in other jurisdictions.

Most importantly, the market is clearly concerned about the outlook for UK inflation in the wake of the Budget. The fear is that stubborn inflation will slow the pace of interest rate cuts, adding another headwind to the UK’s already bleak growth outlook. Stagflation, in a word.

This implies that if inflation appears to be under control, then the sell-off should ease. So what should we make of the outlook for inflation ahead of Wednesday’s figures?

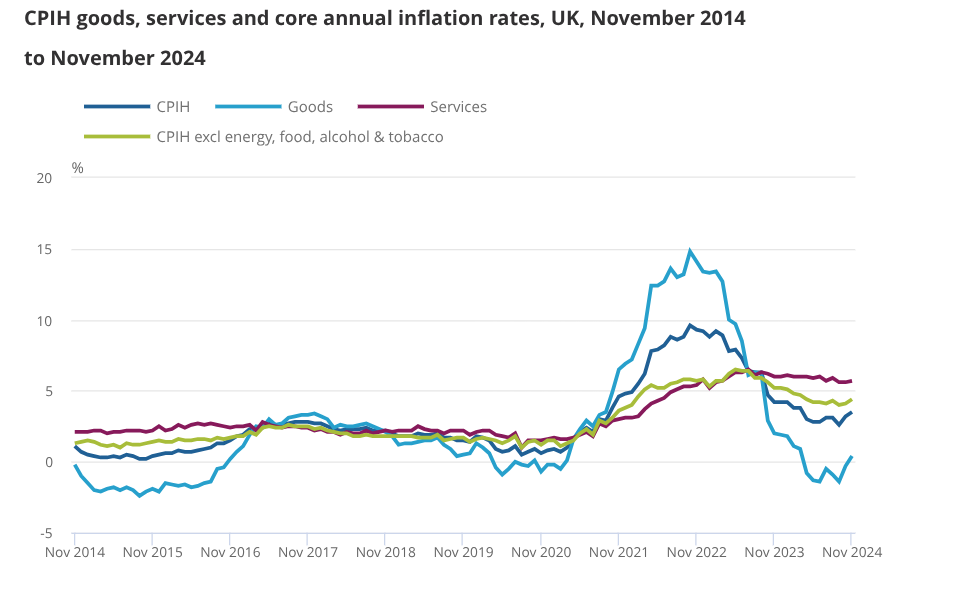

The headline rate picked up to 2.6 per cent in November, which was more or less in line with expectations. The increase was largely driven by higher energy prices, as last year’s steep declines fell out of the annual comparison.

Services inflation, which is the most important gauge of homegrown inflation, remained at five per cent in November, which was actually slightly below expectations.

When December’s figures are released on Wednesday, economists expect headline inflation to remain at 2.6 per cent, but think services inflation will fall below five per cent.

If this plays out, there’s a strong case to cut rates at a faster pace than markets currently expect.

Analysts at Nomura have pointed out that price increases in the services sector have average 0.2 per cent month-on-month for the past quarter, or around 2.8 per cent on an annualised basis.

This puts services inflation roughly in line with the pre-pandemic average.

Add in evidence of a cooling labour market, sparked in part by the government’s Budget, and it seems many measures of underlying inflation are moving in the right direction.

And yet markets expect just two interest rate cuts this year. In a note published last week, analysts at HSBC said that the market implied rate for interest rates was a “puzzle”.

“We think the UK no longer faces a unique inflation problem. If anything, the UK has already seen a more decisive turn in the labour market than the eurozone. And services inflation momentum is now more comparable with the US and eurozone,” they wrote.

Still, the case for caution for greater caution on interest rates is attracting increasing support.

A number of recent forecasts – including from Deutsche Bank, Oxford Economics and Pantheon Macroeconomics – indicate that inflation could rise to as much as three per cent by April.

Why? First, the upward pressure from higher energy prices will continue to push up on the headline rate for the next few months.

The energy price cap rose by 1.5 per cent at the start of this year and Deutsche Bank expects to see a further three per cent increase in the second quarter.

A weaker pound has also added to fears about inflation, because it makes imports more expensive. Sterling has weakened significantly against the dollar, hitting a 14-month low on Monday.

However, this is as much a story of dollar strength as the pound’s weakness. The pound has weakened against other currencies, but not to the same extent. This should limit the extent of imported price pressures.

“The move in trade-weighted GBP has been limited so far, and as yet is unlikely to be a major source of inflationary concern,” analysts at Goldman Sachs said.

Further weakness in the pound against other currencies is possible, but not a certainty.

Most worrying, however, is the risk that forecasters have underestimated the boost to inflation from the Budget.

Both the Bank of England and the OBR expected the Chancellor’s tax hikes to push up on inflation, but both bodies thought the impact would be limited.

The OBR thought firms would be more likely to cut back on wages, while the Bank expected businesses to absorb more of the extra costs.

This was essentially based on the judgement that demand in the UK economy remained weak, and so firms would struggle to pass on higher costs to consumers without putting off buyers.

This was always more of a hunch than a conviction call, but surveys since the Budget have suggested that price hikes are more likely than either body had anticipated.

The Bank’s decision maker panel, for example, showed that over half of firms expect to raise prices in the coming year.

It is worth noting that these sorts of surveys do not show how much prices will go up, but the early indication is that it will be by more than forecasters had expected.

The question then is whether it would force the Bank of England to cut rates more slowly, even though the economy is performing worse than expected.

Remember, three members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted to cut rates in December, demonstrating that dovish sentiment is growing on Threadneadle Street.

With continued signs of services disinflation and a weakening labour market, the case for cutting rates three or four times will remain intact even if the headline rate strays a bit further from target.

Investors will want to see concrete evidence before betting on further rate cuts though.