Don’t bet on India’s Modi to be the pro-growth candidate he’s touted as

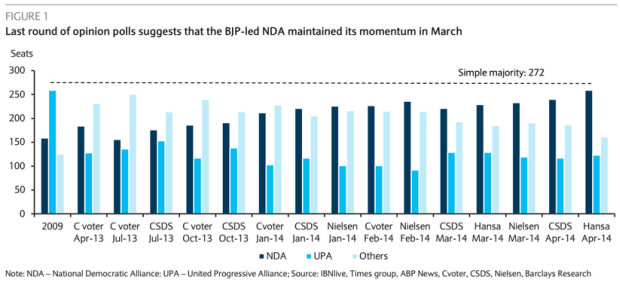

Narendra Modi looks likely to become India’s next Prime Minister – polling in recent months has indicated that his party and its umbrella coalition (the NDA) are set to win the current election.

Modi is often described by journalists as pro-business or pro-market, willing to cut through the country’s stagnant bureaucracy and boost sluggish growth.

For the last 12 and a half years, he has been chief minister of Gujarat, one of the country’s fastest-growing states. But despite his perception as a great economic administrator, there are a number of reasons to be sceptical of this public image.

1. Modi took over an already strong Gujarat

The Economist’s leading article recently said that “Modi’s performance as chief minister of Gujarat shows that he is set on economic development and can make it happen”, a good example of his popular perception in western media.

According to analysis in India’s Economic and Political Weekly, Gujarat is a faster-growing state, but that was true almost a decade before Modi became governor, and there hasn’t been a significant acceleration during his tenure.

The authors suggest that Gujarat was already growing at a more rapid pace than India and “did not experience any further acceleration of growth in the 2000s relative to the 1990s”.

Excluding an earthquake-prompted drop in 2000-2001, just before Modi became governor, Ghatak and Roy indicate that net state domestic product (NSDP) per capita for Gujarat has outperformed India in a similar way since the early 1990s.

2. And it might be because the state population is younger

A paper from the International Monetary Fund in 2011 draws attention to Gujarat’s very favourable demographic picture.

In 2001, 60.6 per cent of Gujaratis were of working age – in Uttar Pradesh, the rate is just 52.5 per cent, and the authors indicate that future growth is likely to come from the states with poorer performance so far, not the current stars:

The states in the south and west of India have already undergone the major part of their demographic transition, while the laggards have not. We are unaware of any state-wise projections of the evolution of the age-distribution over the next few decades.

But considering that the average 2001 working age ratio among the leaders was 62.1 percent versus 53.4 percent in the laggards, it seems very likely that the bulk of the projected large increments to India’s working age ratio will come from the laggards. Sustained growth acceleration in India’s poorest states may now be feasible.

3. Some of Gujarat’s development measures haven’t kept up with growth

Ideas for India, which stems from the Department for International Development (DfID) and LSE, notes that in many non-economic development indices, Gujarat has dropped in state rankings.

Though the state is in the top five for output growth in manufacturing, agriculture and services, but it is improving less quickly in terms of access to public utilities and basic private and financial infrastructure.

The authors, Ashok Kotwal and Arka Roy Chaudhuri note that the failure to make up any ground in these “backwardness indices” is “a total surprise given the common perception”, with Gujarat falling into the middle of the pack during Modi’s time in office (India has 28 states).

They also note that it’s true of Gujarat’s educational outcomes, but struggle for a reason that robust economic growth hasn’t translated into meaningful improvements in these areas: “Could it be that the centralised model of governance that works well for big investment projects, does not work as well for grassroot institutions?”

4. The BJP manifesto is hazy on India’s deficit

Societe Generale’s Kunal Kumar Kundu sees a lot of positive elements in Modi’s party manifesto, but notes that other than an insubstantial commitment to “fiscal discipline”, there isn’t a concrete strategy to reduce the country’s chronic public deficits.

The BJP’s manifesto says that the country’s fiscal and current account deficits are in the “alarm zone”, but Kundu concludes that “the manifesto gives the impression that the BJP government would also continue to walk down the populist path, which can conspire against the goal of fiscal discipline.”

An upcoming gas price hike will prompt difficult decisions over whether to increase agricultural subsidies, which would exacerbate the dreary fiscal outlook.

That’s not to say that any other party has a particularly good plan to firm up the country’s public finances, which have been poor under Congress, but the BJP programme has not yet been laid out fully.

I am indebted to Tyler Cowen and the commenters on his blog for resources and information about Modi and Gujarat.