Does raising interest rates actually bring down inflation?

Britain’s inflation problem is looking much harder to solve than first thought.

Numbers out from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) yesterday revealed the rate of price increases was unchanged in May at 8.7 per cent. The City thought it would slim to 8.4 per cent.

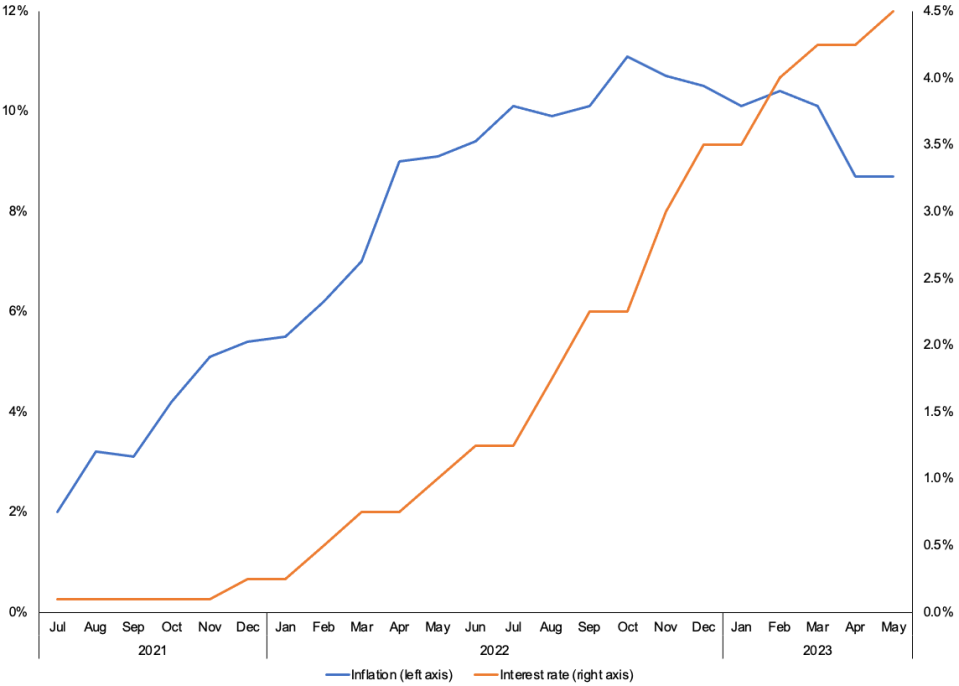

Elevated living costs come despite the Bank of England raising interest rates 12 times in a row to 4.5 per cent. The central bank is tipped to lift them again today, either by 25 or 50 basis points.

Interest rates have for centuries been used to affect prices in an economy. Raising them lifts the price of money by making it more costly to borrow, which should, in theory, put downward pressure on inflation.

In the UK, the Bank of England’s nine-strong monetary policy committee has been in charge of setting official borrowing costs since 1997. It announces interest rate decisions every six weeks or so.

“By increasing borrowing costs for consumers, mainly on mortgages, it reduces the amount of disposable income left to spend on other goods and services, lowering demand and reducing firms’ ability to raise prices,” Thomas Pugh, an economist at consultancy RSM, told City A.M.

A reduction in consumer spending tends to make businesses more cautious and likely to lay off staff. As a result, bargaining power accrues to employers, resulting in workers having to accept weaker wage increases in order to stay employed, curbing production costs.

This is a scenario the Bank is keen to generate in order to bring the rate of wage increases down from more than seven per cent. As Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK put it to City A.M., monetary policy is a “blunt tool”.

It’s not just households that are forced to whittle down consumption in a higher interest rate environment.

Costlier loans make returns on investments less attractive or even loss-making, pushing “companies to invest less,” Selfin added.

UK interest rates and inflation have been climbing

Higher interest rates often strengthen a country’s currency, making it cheaper to import goods and services. They also make economic agents more attentive to what they spend their money on, which can channel cash into more productive investments that generate inflation-neutral, sustainable economic growth.

But, changes to monetary policy tend to take a long time to fully impact an economy. This makes it tough for central bankers to set interest rates when inflation is high, especially when they have already tightened policy significantly.

In such a scenario, there is a risk a central bank can overact, raise rates too high and engineer a recession. However, failing to stabilise inflation can be much worse for families and businesses.

Economists have warned the risk of the Bank of England making a policy mistake is intensifying, largely due to UK’s mortgage market restructuring since the 2008 financial market. America’s equivalent, the Federal Reserve, paused raising rates earlier this month to take stock.

In the UK, “the big problem is that the prevalence of fixed rate mortgages now, compared to the early 1990s, means the lag from interest rates rises has gone from around a year to closer to eighteen months,” Pugh noted.

Change is fast approaching. Experts at the economic think tank the Resolution Foundation have calculated average annual mortgage repayments will rise nearly £3,000 for the around 1.5m homeowners scheduled to roll onto new home loan contracts this year with much more punitive rates. Separate analysis from the Institute for Fiscal Studies yesterday found most of this group will lose 20p in every £1 of their disposable income after the remortgage.

According to financial data firm Moneyfacts, the average rate on the 2-year mortgage has topped six per cent.

The grip on the economy from the Bank’s tough hiking cycle is poised to tighten as the year progresses, which experts think will finally rally Britain’s fight against inflation.