Did pumping cash into the economy fuel inflation surge? Bank top official says claim ‘not well supported by evidence’

Claims the Bank of England caused the worst inflation surge in the UK for more than 40 years by printing money are “not well supported by the evidence,” one of its top officials said today.

Ben Broadbent, a deputy governor at the Bank, hit back at critics in a speech at Britain’s oldest economic think tank, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), who argue that pumping into the economy via bond buying has pushed inflation higher.

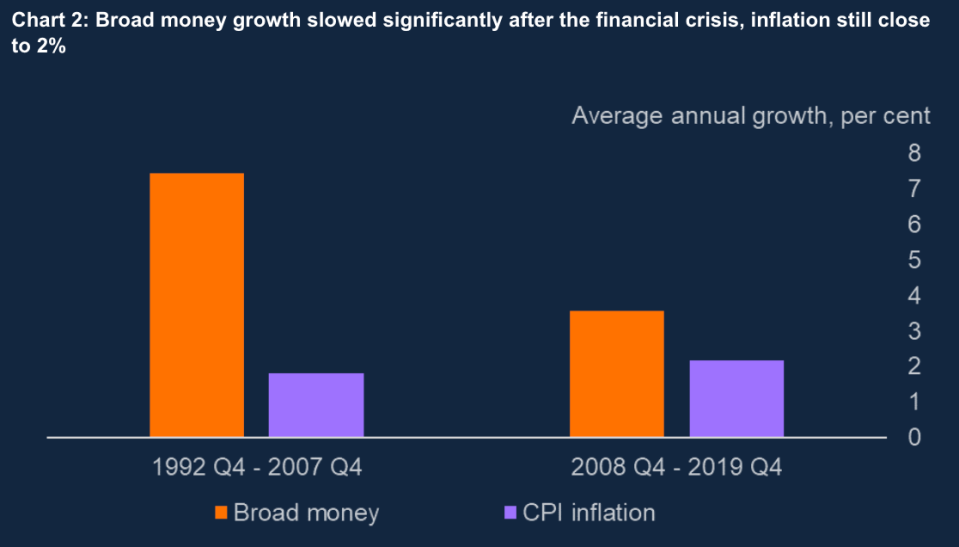

He pointed out that “broad money grew more than twice as rapidly” in the years leading up to the global financial crisis in 2008 “than in the decade or so after”.

“Average inflation, in both periods, was close to two per cent,” he added.

Critics of the central bank – who tend to come from the monetarist strain of economics – say it left its bond buying programme switched on for too long and that it was too generous.

The Bank held nearly £900bn of government and corporate debt at the programme’s – known as quantitative easing – peak.

They argue that injecting cheap cash into banks enabled them to lend to businesses and households at low interest rates, stimulating spending and pumping up prices.

Broadbent criticised that argument for ignoring consumers’ demand to hold money at their bank – essentially saving cash instead of spending it – was quite high, meaning the additional money didn’t entirely reach the real economy.

Instead, he thinks “the more plausible cause [of keeping demand high] is the combined impact of severe restrictions on spending and, thanks in part to fiscal support (in the shape of the furlough scheme), continuing growth in household income”.

“At least in the first instance the resulting jump in saving had nowhere to go but into household deposits,” he added.

Bank officials also constructed a model in which they predicted where interest rates would have had to have risen to to keep inflation at the central bank’s two per cent target amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine jacking up international energy prices and supply chains faltering after pandemic restrictions were scrapped.

“The simulation suggests that interest rates would have to have risen well into double digits,” Broadbent said, adding at the in-person NIESR speech he thought this was somewhere around 20 per cent.

Such a move would have made millions of Brits unemployed and taken the jobless rate into the double digits as well.

Numbers from the Office for National Statistics last week showed inflation fell slower than expected in March to 10.1 per cent, prompting markets to price in a five per cent rate peak.