Demand destruction? Two reasons to be sceptical

Global central banks have made an ‘all-in’ effort to front-load monetary policy tightening to dampen demand. But softer economic data in the eurozone and United States have exacerbated recession fears.

As the growth outlook dims, many anticipate demand destruction to lead to lower inflation. That is, tighter monetary policy and the associated higher funding costs will cut into demand and offset the supply shortages resulting from geopolitical instability and supply-chain disruptions. This view hinges on the belief that inflation outcomes are largely driven by central bank policies.

However, what US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell in 2019 described as ‘muted’ inflation in previous years, especially during the 2014 to 2016 oil-price crash, has demonstrated inflation’s insensitivity to demand-side policies. Even the European Central Bank (ECB)’s quantitative easing (QE) in 2015 failed to stoke demand in a way that reduced excess supply.

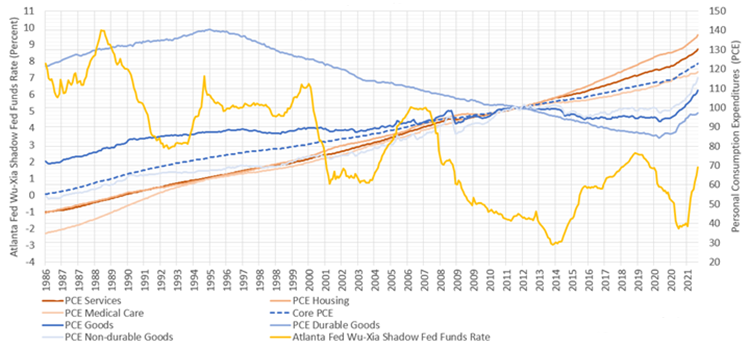

The Fed’s dovish policy stance in the decade before the pandemic pushed the Atlanta Fed’s Wu-Xia Shadow Federal Funds Rate below zero multiple times. Yet the Fed’s preferred price measure – personal consumption expenditures (PCE) – was less responsive to such policy shifts than to the end of the Cold War or China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, among other catalysts.

Personal Consumption Expenditures vs. Shadow Federal Funds Rate

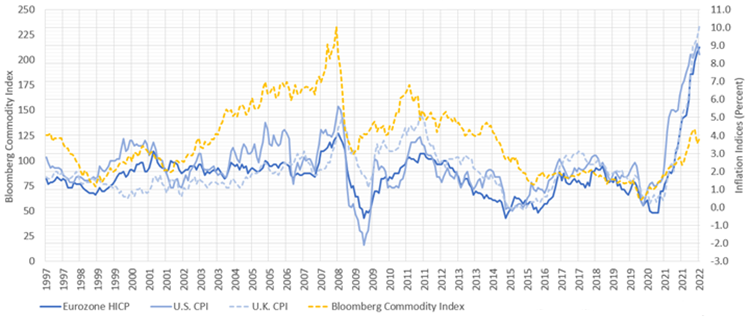

Similarly, recent quantitative tightening and rate hikes have not created enough demand destruction to counteract geopolitics-related commodity scarcity. Instead of following central bank policy over the past two decades, inflation largely co-moved with commodity prices, or both demand and supply-side factors.

Eurozone, US, and UK Inflation vs. Commodity Index

This casts doubts on the ‘rates-determine-activities-determine-inflation’ framework and suggests that domestic monetary policy cannot lift or dampen inflation on its own. Other factors must come into play.

1. Fiscal Spending = Higher Demand

Given QE’s long and variable trickle-down effect, pandemic-era policies sought to counter the demand shortfall by expanding balance sheets and through fiscal stimulus, or printing money and mailing cheques directly to households. This drastically decreased the transmission time between central bank easing and realised inflation. The deployment of ‘helicopter money’ rapidly revived demand.

As pandemic disruptions eased, the anticipated fiscal tightening never materialised. Instead, fiscal-monetary cooperation became the norm and cash payments a regular policy tool. Following its Eat Out to Help Out Scheme, for example, the UK government in May this year announced a £15 billion package to send £1,200 support payments to millions of households. As UK energy prices spiked, Liz Truss, the UK prime minister, proposed an emergency fiscal spending package to ease the public’s financial stress.

On the other side of the Atlantic, many US states have announced stimulus payments to soften the pain of high inflation, and president Joe Biden has introduced a student loan relief programme.

The lesson is clear: central banks are no longer the only game in town when it comes to economic stimulus.

2. Geopolitical Events = Supply Disruptions

As multinationals regionalise, near-shore and re-shore supply chains and prioritise resiliency and redundancy over cost-optimisation, energy scarcity in the eurozone has created new disruptions. German chemical production is set to fall in 2022, which could export inflation abroad.

As geopolitical instability contributes to domestic economic challenges and more fiscal stimulus is deployed, inflation may be much less responsive to traditional monetary drivers. Under such circumstances, a rigid framework equating tight monetary policy and high prices with demand destruction and disinflation will no longer be operable.

For investors calibrating portfolio risks, such conditions may offset the disinflationary pressures of slowing growth.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

By Victor Xing, founder and portfolio manager of Kekselias, Inc., and a former fixed-income trading analyst at Capital Group Companies with a focus on monetary policy, inflation-linked bonds, and interest rates markets.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / desperado