Deflation fear prompts Eurozone rate cut talk

But a single data point is unlikely to convince the ECB that immediate loosening is necessary

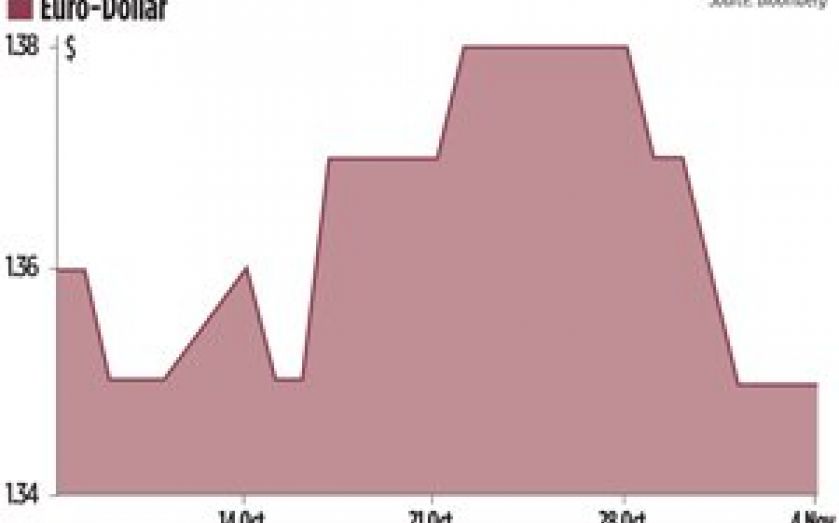

European shares traded close to five-year highs yesterday amid speculation that the European Central Bank (ECB) will cut its policy rate on Thursday. The FTSEurofirst 300 Index rose above 1,296, a near 6 per cent increase from Friday’s levels. Last week, the euro posted its biggest weekly decline since July 2012, and fell to almost $1.349 yesterday from highs of around $1.377 on Thursday.

“The growing clamour for a cut is born mainly out of last week’s inflation data,” says Matt Basi of CMC Markets. Flash estimates saw Eurozone prices rise just 0.7 per cent year-on-year in October, close to four-year lows, while a revision to August’s unemployment data showed the jobless rate increase to a record high of almost 19.5m. Both UBS and RBS now expect a rate cut from the current level of 0.5 per cent at Thursday’s meeting.

But it is by no means obvious that the news flow has been sufficiently worrying to warrant an immediate loosening of policy. And as Adam Cole of RBC Capital Markets says, “contrary to those who see the ECB rate as key, it is not clear that a cut would achieve a great deal with market rates already so low.”

DEFLATIONARY FEARS

The fear that the Eurozone could slip into deflation, as in 2009, has prompted many to call for even looser monetary policy. Greece saw prices fall at an annual rate of 1 per cent in September, while Ireland, Spain and Portugal experienced inflation of less than 0.5 per cent. Capital Economics, in a note yesterday, said that “a bout of deflation could severely hamper the efforts of the peripheral economies to prevent their sky-high debt-to-GDP ratios from rising further.”

Cole adds that “a second factor is the ongoing strength of the euro.” Before its recent slide, the currency had set a two-year record high against the dollar at more than $1.38 (see graph) towards the end of October, and had risen 6.5 per cent against a basket of currencies since the beginning of the year. Further appreciation would hurt the export growth the struggling periphery is relying on, and many fear it could add to disinflationary pressures.

NO KNEE-JERK REACTION

Despite these dangers, a single data point does not constitute a deflationary spiral, “and it’s simply not in the ECB’s nature to react in a knee-jerk way,” says Basi. Moreover, a break-down of price figures reveals disparities across the bloc. Although former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi has accused Germans of being “obsessed with inflation”, many fear a potential asset price bubble in Germany, with the Bundesbank recently warning that properties in some cities may be overvalued by as much as 5 to 10 per cent.

And regardless of the legitimacy of deflationary fears, Simon Smith of FxPro points out that ECB rate changes would likely have a minimal effect on market rates and economic fundamentals. “While the ECB’s benchmark rate is 0.5 per cent, money market rates are below 0.10 per cent out to a one-month duration,” he says. The ECB rate was cut from 0.75 to 0.5 per cent in May, but its cost of borrowing indicators barely fell between April and September – from 3.01 to 2.93 per cent on the composite measure.

“It is more likely that Draghi will just signal a dovish tone, and possibly a new Long-Term Refinancing Operation on Thursday,” says Basi. Doubts remain over the effectiveness of another liquidity programme, but Basi expects a euro relief rally if rates are unchanged. “We could see it edge back up above $1.36 in the coming weeks,” he says.