Daddy review: Queer ecstasy and vulnerability in ambitious play with uneven script

Wearing Versace as he greets ticket holders outside the Almeida theatre, Jeremy O’Harris looks and acts like the star playwright he’s fast becoming. He has the cultural cache to boot: He’s the burgeoning writer who consulted on the script for Euphoria and broke onto Broadway with the controversial Slave Play, nominated for Best Play at the Tony Awards.

The press night for Daddy is as glamorous as its writer’s outfit. I’d wager most ticket holders were born in the 21st century, and most compete with O’Harris in the sartorial stakes. There’s the type of buzz you’d associate with the opening night of a show starring a Hollywood name.

It’s been a long road for Daddy, which was delayed by two years due to, well, you know what. In that time Daddy and O’Harris were often name-checked in ‘shows to catch’ lists, which built hype.

The end result is a brave and audacious play about exploitation and identity which looks a million dollars but eventually loses some of its meaning in its own stylishness. Terique Jarrett plays Franklin, a young black artist who believes art innately loses its creative value when it’s sold for cash. Claes Bang plays an older white man called Andre, a charismatic bastard with a lot of money who puts Franklin up in his Bel Air mansion and exploits how impressionable he can be.

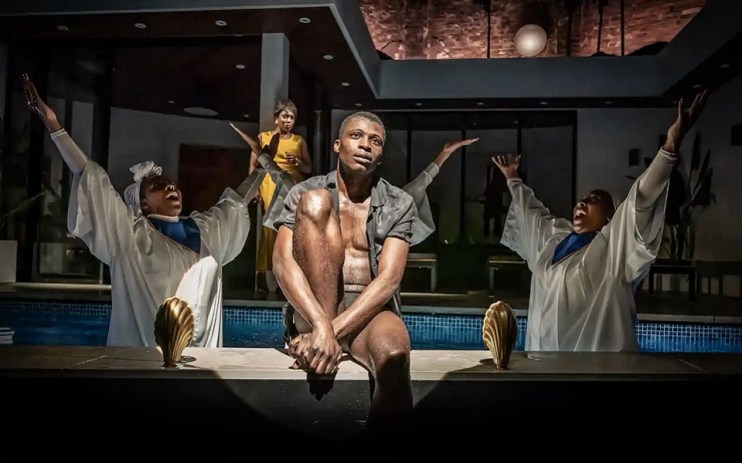

Matt Saunders’ set really feels like an L.A. house – there’s even a proper swimming pool actors splash about in. The set makes both the darkest and brightest corners of O’Harris’ script shine. There are riotously fun displays of hedonism, as Franklin’s young friends exploit Andre’s insane house, rocking up to snort lines from sun loungers while he’s out of town. Then there’s the horrible, coercive control wielded by Andre over Franklin which drives the plot, feeling even darker against this backdrop of serenity and sunshine.

Terique Jarrett is sublime as Franklin, fitting like a puzzle piece inside the arms of Claes Bang’s Andre, as they entangle themselves in each other’s bodies hanging out around the pool. Their chemistry is off the scale.

Interludes of melodrama seep into director Danya Taymor’s gleefully chaotic direction. They’re mainly well judged and genuinely funny, but occasionally – like the ode to ‘90s boy bands Andre sings to the audience with a hand-held mic – feel crass. Moments like this feel at odds with O’Harris’ message about how a young queer black man can be manipulated. By the second and third acts, style overrides substance more often than it should.

By the end, Daddy feels like riffs on a theme O’Harris is passionate about rather than a single, cohesive story, but the strength of the production means Franklin’s story is still heard.

Daddy plays at the Almeida Theatre until April 30