Credit Suisse and Silicon Valley Bank chaos are symptoms of fragile banking system

City folk around in 2007 must have been getting very twitchy over the last week.

Some of the market moves were reminiscent of the early stages of the financial crisis once people clocked on to just how bad banks had messed up.

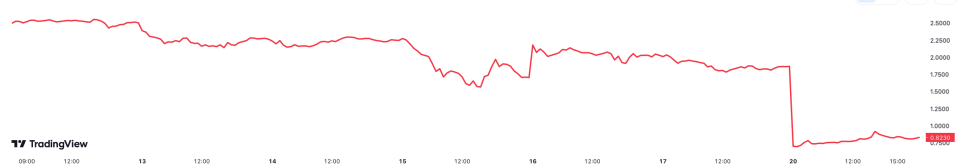

Credit Suisse tumbled more than 30 per cent at one point. Its peers BNP Paribas, Societe Generale and UniCredit all had their shares suspended. Deutsche Bank slid, as did Barclays, NatWest and Lloyds.

It’s still not clear at this point what had rule makers so spooked that they had to fold a company that has been around since 1856.

The whole fiasco is very troubling and happened because, at its core, the modern day banking system has an inherent level of risk that’s hard to contain.

Banks play an important function in allowing cash to flow around an economy.

At their very basic level, they take in cash from people who are not using it for immediate spending and lend it to people to use it more productively.

Businesses get off the ground because banks dish out depositors’ capital. That generates a return which they use to fund interest on savings accounts.

Without that broker in an economy, resources would get tied up, growth would be lower and jobs would be lost.

It’s worth mentioning that the rapid expansion of financial markets over the last century – turbocharged since regulation was rolled back in the 1980s – has meant the global banking system has been split in two.

Retail banks perform the function described above.

Investment banks are very, very different. They lubricate stock markets, not the real economy.

Credit Suisse’s share price has collapsed over last week

They insure companies against losses on new listings and when raising cash by selling off a segment of their firm.

They also participate in capital markets, especially debt markets, where they are what economists call “market movers” meaning their actions exert a heavy influence over the direction of asset’s share price.

It’s that participation in debt markets has come under scrutiny recently.

While not strictly an investment bank, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) had an enormous exposure to the US treasury market.

It hoovered up American government debt when interest rates were low and bond prices were high (the pair move inversely) to both make sure its balance sheet added up and comply with US banking rules.

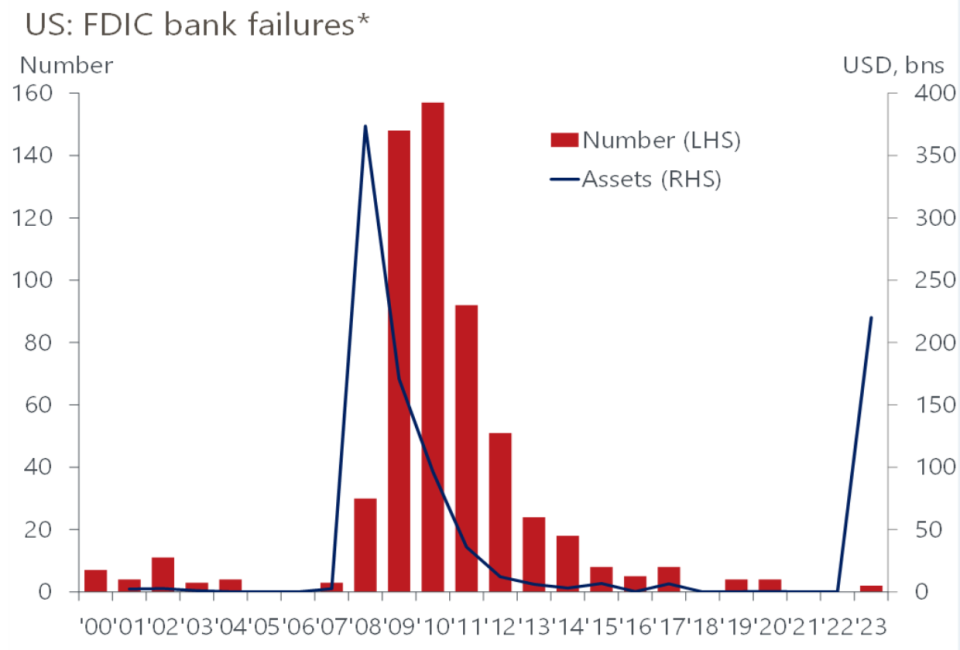

As a result, SVB’s financials crumbled. Those keeping close tabs on it realised what was happening and pulled their cash. They warned others to do so. A bank run followed, culminating in SVB becoming the second largest banking failure by assets (around $250bn) in American history.

SVB is second largest US bank failure ever

It is at this point the divide between investment and retail banking blurs.

Bank runs share characteristics with investors ditching stock in a company they don’t like. People realise something’s fishy, want to protect their stake as much as possible and get out before things get worse.

That very action makes the situation worse.

No one involved in the situation has an incentive to work collectively. If everyone held their respective stakes, then the price could withstand pressure. However, if one person sells before the other, they’ll probably rescue a greater amount of their cash.

It’s your classic prisoner’s dilemma.

A dynamic in which a wave of people rush to rescue their savings and store it elsewhere is ruinous for a bank.

Because banks take in deposits that can be called upon at any time and loan those deposits to people who repay it over years if not decades, it means they never at any one time have enough cash on hand to repay all their customers at once.

Panic ensues. The bank ditches its assets in a fire sale to find money to meet deposit demands. Stakeholders pick up on this and rush to save their money. A vicious cycle continues until the bank fails.

That’s exactly what happened to SVB earlier this month.

Not all wobbles in the banking sector are sparked by the same trigger. This time round it was a sharp rise in international interest rates. In 2008 it was prompted by borrowers being unable to repay cash they never should have been lent once the US economy slowed down.

Banks borrow short and lend long, which always gives them a level of underlying risk to changes in sentiment. Beefed up regulation since the financial crisis has watered down some of those risks though.

But once one bank fails, the tide of opinion changes, causing stakeholders to look to other potential bad players in the sector. Last week they zeroed in on Credit Suisse, which has looked shaky for many years.

Some £45bn had to be injected by the Swiss central bank into the once poster boy of European banking to keep it chugging along, helping to restore market calm. Then something happened over the weekend that forced Swiss regulators to push the nuclear button and force through a tie up with UBS.

If there’s anything this episode should have taught us it is that when economic conditions suddenly change, banks can get caught out.

Governments, regulators and central banks will always stand behind the banking sector to tame any contagion.

But the world’s largest financial institutions are not immune to everything.

WHAT I’M READING

The Resolution Foundation’s post-match analysis of the budget makes for pretty grim reading. Yes the fiscal situation has improved (a bit) since November, they reckon. But the outlook for living standards is dire, which chimes with the Office for Budget Responsibility’s forecast that we’re in for a 5.7 per cent real income hit, the largest on record. The IFS thinks families have lost £10,000 of real income growth since the financial crisis. Bad all round.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s decision to scrap the pension lifetime allowance will cost about £3bn but will only keep about 15,000 more people in the workforce. That’s a bill of about £80,000 per worker, more than what most of those people probably earn a year.