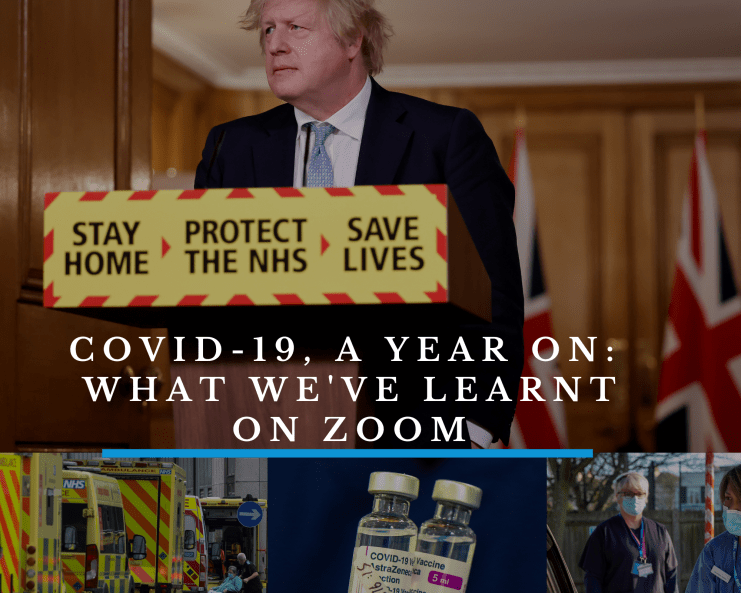

Covid-19, a year on: What we’ve learnt on Zoom

In this series, City A.M. looks back at the last year of the pandemic and Covid restrictions and takes stock of its impact on industries and issues at the heart of British society.

Read more: Read the full Covid-19, a year on series here.

Over the last year, the language we have used has changed. Words like asymptomatic, lockdown and curfew have become commonplace. The way we have communicated is also different. Our new lexicon is full of new phrases: “You’re on mute”, “Do you want to screenshare?” or “My video isn’t working”.

As we chart our way forward, the temptation will be to tar our experience of Zoom as love it or loathe it, which will likely correlate with our individual desire to work in an office, or not.

The most obvious and oft-cited consequence of a year on Zoom has been a loss of physical touch, the rich web of interpersonal connections we form by being in the same room as other people.

The heart of a conversation, the bit that’s alive, is not always the words we use. How often do we hear this caveat, “it’s how it was said”, when relaying a conversation? So much of the “how” clause is lost over Zoom. Were our friend’s shoulders hiked up to their ears with stress and anxiety, was that a waiver in their voice or was it a dodgy connection?

In our normal lives, we interpret the nuance of conversation on a subconscious level. This past year, we have had to work harder to decipher it. Perhaps few appreciated the full extent of this change more than those who trade in emotions: psychotherapists.

“When speaking to clients, you aren’t getting the full picture, it can be exhausting having to try and read their body language, for example. You don’t realise how much information you have been getting from that, until it’s not there,” says Michelle Scott, an Edinburgh and London based psychotherapist.

But, by the same token, where a client positions themselves at home, what they wear, can be more revealing than if they had moved seamlessly, pre-Covid, from their day-to-day life outside home to a therapist’s room. “You learn quite quickly how to tell how someone is in other ways, how they’re dressed, whether they’re in pajamas, for example, as well as where they are sitting, are they in bed, or are they sitting at a desk as though therapy is just part of their work,” Scott says.

A similar breakdown has played out in our professional lives. Suddenly, no one is sitting around boardrooms in suits in the preconditioned cut-outs of how we think we should be. A taboo, peering into our neighbours’ windows, has now become our norm.

We have scrutinised our boss’ bookshelf, seen the jar of peanut butter still open on the counter, heard a child’s demand for attention and peered into our colleagues’ private spaces. While we were shuttered off from each other when office doors swung shut, something deeper has been opening up in our conversations.

This dissolution of boundaries between the personal and the professional has engendered a vulnerability not possible in our pre-pandemic working lives. And, crucially, it has allowed empathy to flourish in an environment normally operating within the strict confines of “work”. Zoom has given us a platform to understand our colleagues’ and friends’ lives better, as much as it has taken away our ability to see them physically.

Along with this, there has been a new intensity to our interactions. So much so that “Zoom fatigue” piqued the interest of researchers at Stanford University. The study, led by Professor Jeremy Bailenson, found one of the key reasons that Zoom exhausts us is we’re constantly looking at one another. When we have prolonged close eye contact with someone, our brains are trained to interpret that as an intense situation.

“In general, for most setups, if it’s a one-on-one conversation when you’re with co-workers or even strangers on video, you’re seeing their face at a size which simulates a personal space that you normally experience when you’re with somebody intimately,” Professor Bailenson says.

Unhappily for many, silence has been absent during our year on Zoom. While the high streets and offices were eerily quiet, those normal lulls in any face-to-face conversations went missing. Without a shared environment of buses moving, a clock ticking, a waiter’s funny smile, silence became more awkward, more difficult to hold. Looking away during Zoom is easily interpreted as rudeness.

It was Mia Wallace in Pulp Fiction who said: “Don’t you hate that? Uncomfortable silences. Why do we feel it’s necessary to yak about bullshit in order to be comfortable?

“That’s when you know you’ve found somebody special. When you can just shut up for a minute and comfortably enjoy the silence.”

Relying on Zoom for the bulk of our conversations is a personal hell for people like Mia.

The vaccine rollout means we will, finally, begin cultivating many of our relationships in real life again. But Zoom is undoubtedly going to be a part of our personal and professional lives going forward. Even as office doors fling open, the seismic shift of the last year will stay with us.

Deciding which of our meetings happen online and which happen in person will be a challenge for businesses and individuals.

Head of International at Zoom, Abe Smith is no exception to that dilemma. Zoom itself plans to return to some face-to-face meetings, where necessary.

“While I do think there’s incredible value in meeting people personally, there’s a time and a place for that. But there is also a time in a place to say there’s a lot of value, on a productivity level, and on a personal level to be present and to be home,” Smith says.

“I don’t plan to go back to where I was in 2019 or 2018 or before, but I do plan to travel again, and (Zoom) do plan to have a hybrid environment on how we work. In general, we practice what we preach.”

For Zoom, it’s not about changing people’s entire lives or work routines, but offering a new way to communicate. At the beginning of 2020, Zoom logged 1.3 billion minutes of video calls. This year, they are heading for over 3 trillion minutes.

In spite of the obvious tensions, Smith envisages a symbiotic relationship between the office and video conferencing. Offices are not the competition, he says, and Zoom will be a beneficiary of a return to workplaces. Less than 5 per cent of conference rooms around the world are enabled for video meetings, going forward, Smith expects that number to skyrocket.

As we make our way out of our pandemic dens and back into the world, many will relish the freedom from our laptop screens. But as Covid-19 recedes we might also cherish coming to know more about fellow workers from being invited into their private spaces.