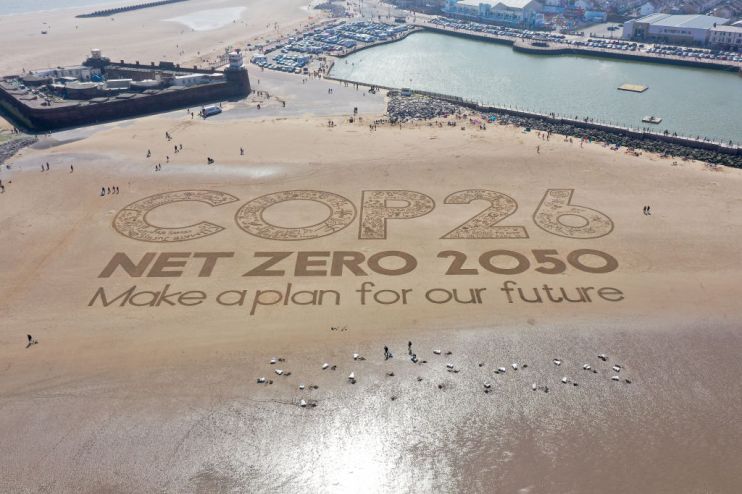

Green with envy: companies around the world have pledged to go net zero without a plan to get there

There has been an avalanche of commitments to reduce emissions, from private companies to governments around the world. More than 20 per cent of the world’s largest corporations have set net zero targets and most major economies have committed to achieving net zero by the mid century.

Yet, with the existing policies, we are currently on track for the world to warm by 2.9° – wide of the 1.5°C mark. There is room for movement here – government pledges could bring this down to 2.4°C. On the other hand, some estimates suggest that on the basis of the climate targets of the FTSE100, the globe will warm by 3.1°C.

There is a huge concern over the validity or credibility of net zero targets. It’s no surprise therefore, that in the run up to COP26, just as countries are being pushed to back up their commitments, companies too are facing pressure to publish more details on their transition plans.

Lots of these long-term commitments will only be fully achieved (or not) in 30 years, so it is vital that companies also set interim targets. This allows management to set action plans they can actually deliver on, without kicking the can down the road and raising future risk.

Crucially, these targets must be aligned with what climate science says is required, cover emissions across the whole value chain, and be validated and verified externally to avoid potential greenwashing.

The gold standard of verification is the Science-Based Targets Initiative, which applies stringent benchmarks to validate targets in line with the science, and brings much needed standardisation and rigour to the space.

Many companies’ net zero targets are unachievable without a sustained effort. Companies can’t simply publish ad hoc sustainability statements when they need a good news story. With every commitment, there should be a transition plan, with clear timelines and indicators setting out the when and how. This should include tangible financial and strategic metrics, such as CAPEX, R&D, products and services, and management incentives.

Within the transition plan, there need to be key review dates. Business leaders know how to get the job done when they want to. They know the outcome is a result of the sometimes thankless task of making mistakes and getting back up, but they need to know if they are making the mistakes or not.

There need to be multiple levels of accountability within organisations, for example, public companies could be required to make their progress on their climate commitments available to shareholders in the same way other financial metrics are.

At the very heart of this accountability is transparency – only with clear and regular disclosures can a company show stakeholders that it’s upholding its public commitments.

It is hugely encouraging to see many countries start to shift towards systems of mandatory climate reporting, these are watershed moments for transparency in a space all too often dominated by woolly claims. But the regulation does not yet hold companies accountable for their commitments. Investors, shareholders, NGOs and citizens need to fill this gap.

Individuals across the world are making changes to make their lives more sustainable, from ditching plastic to eating less meat. These efforts will mean little if the biggest polluters don’t follow suit.

We are already seeing dramatic consequences of climate change at just 1.2°C of warming, urgent action is required now – there is no time to wait.