When the chips are down: the tiny piece missing from our supply chains

If you haven’t already bought your tech gifts this Christmas you may have to come up with some more primitive alternatives for your loved ones.

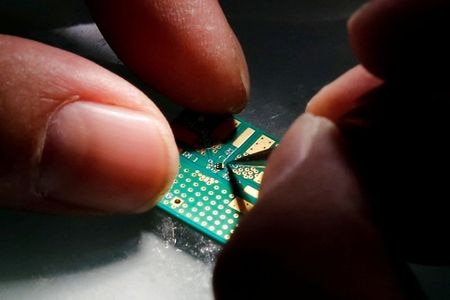

Chronic shortages of chips, the tiny semiconductors that are essential to a myriad of technologies, as well as high labor and transport costs, mean that Christmas gifts this year such as video games, consoles and iPhones, will be much harder to come by. Retailers and chip manufacturers alike are warning that the situation does not appear to be resolving itself anytime soon.

The chip shortage is a significant contributor to the global supply chain issues that have plagued the world since Covid hit. While the latest figures show that things are improving in the US, supply shortages in the UK and euro area are only getting worse, with the orders-to-inventory ratio at factories and shops across Europe continuing to rise.

The list of goods affected by the chip shortage spans all sectors.

One key industry is cars. According to Alixpartners, the cost of the chip shortage is set to cost automakers around $110bn, with the average vehicle containing 1400 chips. And Elon Musk has criticized the largest chip manufacturers for the supply shortages, which have hampered Tesla production.

Video game producers have also been hit especially hard, as the chips are essential for their output. Nintendo had to drastically cut its production plan of consoles due to the shortage, and stocks of the next-generation consoles, Xbox Series X and PlayStation 5, have been continually running low since the beginning of the pandemic.

The heavy start-up and running costs of semiconductor plants mean ramping up production, through new competitors, is difficult. Instead a few behemoth firms exist. Most of the largest chip producers are based in Asia, including Taiwanese TSMC and South Korean Samsung.

The US, which once produced 37 per cent of the world’s semiconductors and now accounts for just 12 per cent, is fighting hard to regain some of its market share. Bipartisan legislation has been passed by the Senate which includes $52bn towards chip manufacturing and the formation of a National Semiconductor Technology Center to focus on research and development.

The UK on the other hand is, for all intents and purposes, out of the race altogether. Brexit meant the UK missed out on a new semiconductor factory from Intel, who instead decided to focus on the EU market.

The factors driving the shortages have grown out of an environment changing at such speed, without enough time to catch up. The increased reliance on technology prompted by the pandemic caused a spike in demand for devices, from laptops to monitors to facilitate home-working and communication.

While the rollout of 5G increased demand for chips more broadly, demand for new devices which took advantage of the network soared. The current shortage has since had knock-on effects on this rollout.

Last year, the Trump administration effectively banned the sale of chips and other technologies to Chinese tech giant Huawei through to April this year – an executive order President Biden has kept in place. This meant chip makers outside the US were flooded with orders.

There were also a string of other setbacks including disasters in Texas and Japan which slowed production. Simon Segar, CEO of one of the world’s largest chip manufacturers, ARM, says that even the billions of extra spending to add capacity won’t be enough to overcome these issues.

The ongoing crisis is a stark reminder of how important these tiny semiconductors are to our everyday lives, and of the importance of supply chain resilience and competition. The lack of goods is not the only consequence, as the stability of workers’ jobs is jeopardized as factories face having to close while they wait out the storm of shortages.

Billions have been pledged to try and remedy the situation, and get things back to normal. For now, expect longer wait times for the latest gadgets and new cars and a few disappointed faces this Christmas.