Can carbon capture boost supply security and the UK’s green agenda?

Throwing soup over precious artworks and scaling bridges to bring traffic to a standstill are certainly eye-catching displays of climate activism.

However, they obscure the reality that if the UK ‘Just Stopped Oil’ there would not even be enough power left to gloat on Twitter about it.

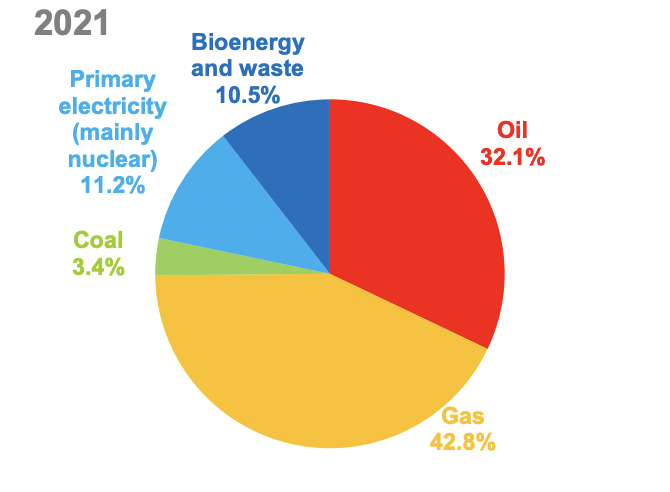

Oil and gas combined still represents over 70 per cent of the UK’s energy consumption, according to the latest Government data.

Meanwhile, the Climate Change Committee – Westminster’s independent advisory group – predicts 50 per cent of the UK’s energy requirements between now and 2050 will need to be met by fossil fuels, and as much as 64 per cent of UK energy needs between 2022 and 2037.

Currently, the UK meets over half its oil and gas needs from North Sea extraction, but the continental shelf is a dwindling, mature site.

The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) has warned in its resources report that without further exploration the UK faces a cliff edge in production decline and increased reliance on overseas imports.

This is especially significant following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has eroded the appeal of being heavily dependent on overseas vendors to meet the country’s energy needs.

It doesn’t help that developments have stagnated since the pandemic.

Industry group Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) recently published its economic report on the sector, which revealed that just five exploration wells were drilled last year.

This was the lowest total since the North Sea was opened up to development nearly 60 years ago.

OEUK also forecasts 15bn barrels of oil could still be extractable from the continental shelf – enough to provide 15 years’ worth of supplies to meet the country’s needs as it transitions to low-carbon power.

This explains the Government’s clamour to boost domestic oil and gas production, with the latest licensing round for oil and gas expected to attract over 100 licenses.

However, further exploration and drilling will boost greenhouse gas emissions, which runs counter to the UK’s ambition to reach net zero carbon emissions over the next three decades.

This is where the industry hopes carbon capture and storage (CCS) comes in, with oil and gas bodies hoping it can play a role in containing emissions for essential new projects.

What is carbon capture and storage?

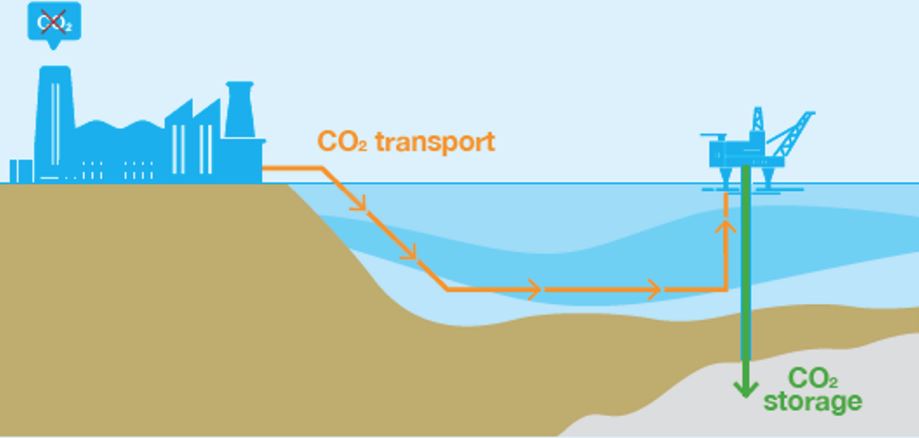

CCS involves the capture of CO2 emissions from industrial processes onshore.

This can include the refining of oil and processing of gas in power generation, or capturing emissions from factories with steel and cement production. The emissions are then transported, typically by ships or pipelines, and injected into deep underground geological formations in the North Sea.

The UK launched its first ever carbon capture licensing round this summer, attracting 26 bids from 19 companies for new projects, with licenses to be awarded next year.

This follows the Government unveiling the carbon capture, usage and storage roadmap in April, as part of its energy security strategy.

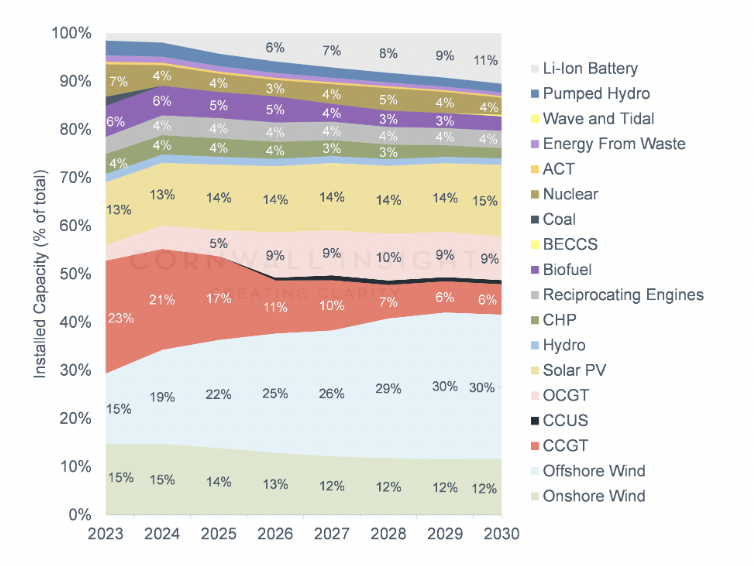

It is targeting the development of four low-carbon clusters to capture 20-30m tonnes of CO2 by the end of the decade.

There are six active carbon storage licences on the UK’s continental shelf, which could store up to 40m tones per by the mid-2030s – around one-fifth of estimated storage needs – if they reach their maximum proposed potential.

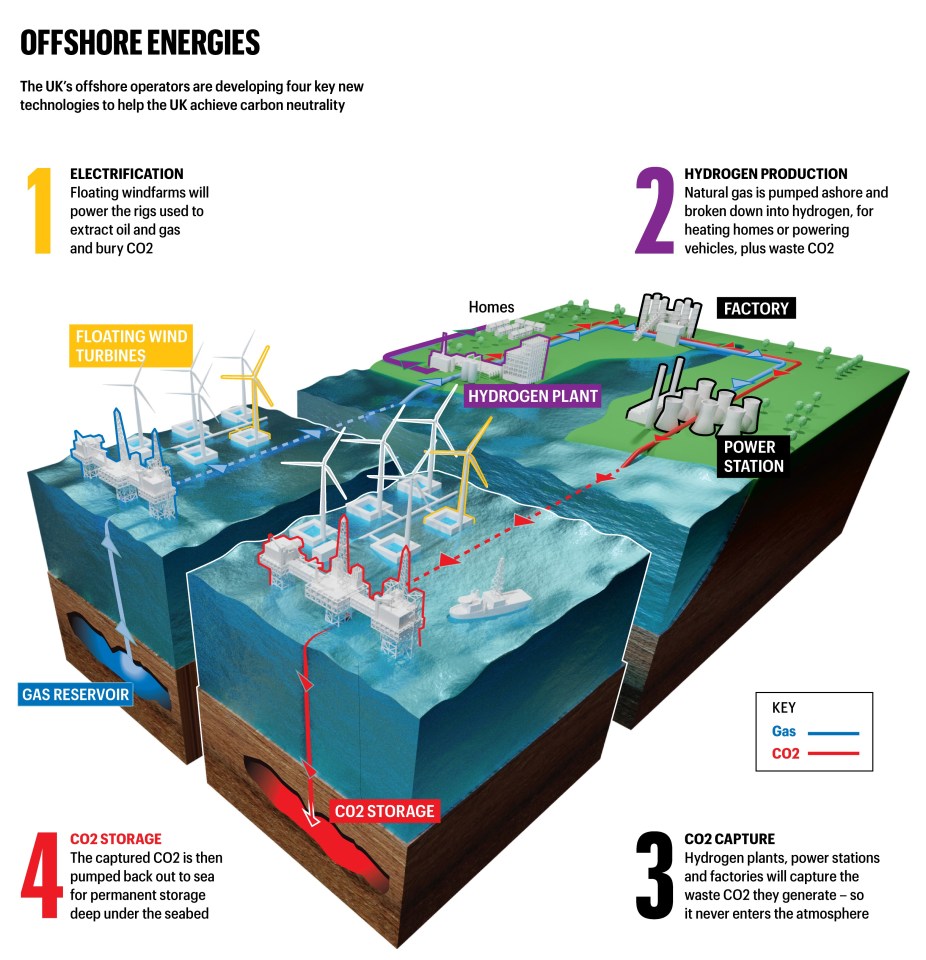

When approached for comment, OEUK said: “As well as being critical for the decarbonisation of industry, CCS is an important technology for continued development of the UK’s energy security, as the enabler for blue hydrogen production and for the development of low-carbon gas-fired power stations.

“Traditional oil and gas companies are taking the lead on the development of all the UK’s cluster projects and supply chain companies transitioning from a sole focus on oil and gas will be crucial for their implementation.”

Meet the players: energy firms with big plans

Major firms involved in CCS include North Sea oil and gas giants such as Neptune Energy and Harbour Energy.

Neptune is aiming to go beyond net zero and store more carbon than is emitted from its operations by the end of the decade.

It recently finalised a deal with clean energy specialist Horisont Energi to develop the large-scale Errai CCS project in Norway – which will have the capacity to store 4-8m tonnes per year of CO2 once its operation.

This is not is first foray into CCS, as the company has a decade of experience operating the K12-B gas field in the Dutch North Sea and the Snohvit field in the Barents Sea.

It is also progressing two developments in the Dutch and UK sectors of the North Sea that could see it store more than 9m tonnes of CO2 per year by the end of the decade.

Meanwhile, Harbour Energy is directing its ambitions through Viking CCS – the company’s £500m purpose-built project with aspirations for CCS in the Humber region.

Viking CCS, formerly known as V Net Zero, is targeting 10m tonnes per year of storage by the end of this decade, and 15m tonnes by 2035.

It plans to hold CO2 emissions created by industry at the Port of Immingham and transfer them to expired gas and oil sites in the North Sea is now in the final consultation stages.

Project director Graeme Davies told City A.M. that CCS allows the UK to offset emissions in “hard to abate sectors” such as cement and petrochemicals.

He argued there are no pathways to net zero that do not involve carbon capture and storage, and CCS could ensure gas power was less harmful during intermittent periods for renewables such as offshore wind.

Davies said: “It’s not stripping finance away from offshore wind, quite the opposite. It’s one of many ways through which the UK can decarbonise to secure jobs and provide energy security. We’re very positive about the role we can play.”

This includes manufacturing, cement, and petrochemicals allowing them to decarbonise and keep their facilities in the UK while meeting climate goals and protecting jobs.

He also praised the Government for backing what remains a complicated process, with BEIS designating clusters, the NSTA overseeing licensing rounds from land typically owned by the Crown Estate, which then gets signed off by Ofgem.

The CCS expert believed that the “UK has really moved forward at pace” in the past few years.

He said: “They’ve put a lot of resources in BEIS, Treasury and other places to developing the business models. It is a really complex process that they’ve undertaken, and they’ve been broadly held to time.”

Pierre Girard, director of new energy at Neptune, said that while CCS presented new opportunities for the UK, it was not a new idea.

It was first developed in the US fifty years ago and has also been established in Europe for decades.

He explained: “There is often the perception that it’s something new, risky, and that this is a new territory. Actually, not at all. It’s been done for a number of years, successfully. This is something we’ve actually done in the offshore environment in the Netherlands for14 years.”

In his view, the UK was in a “great place for carbon storage” due to its geology, and he praised the licensing round and the sector’s embrace of the opportunities.

Not a panacea: Issues remain for carbon capture

Nevertheless, there are concerns that CCS could be presented as a silver bullet for fossil fuel projects, rather than a supplement to the transition to green energy.

Roz Bulleid, research director at Green Alliance, said: “CCS isn’t a panacea. It has several potentially useful applications, particularly for industrial emissions and as part of a system for removing carbon from the atmosphere, and so it’s worth pursuing at some speed to see if it can work in the UK.”

However, she argued that it was unlikely to be the most energy efficient solution compared to “cheap options like domestic renewables” and “reducing demand for energy” through energy efficiency and changing consumer behaviour.

Adam Bell, head of policy at consultancy group Stonehaven, recognised CCS was plausible when it came to “pumping pressurised gas into an undersea void.”

He questioned whether capturing emissions from a manufacturing facility could help meet net zero goals unless it was 100 per cent efficient, which has not been achieved at any North Sea project.

Bell explained: “There are some challenges around capture , especially the relative efficiency of the amine cycle used for post-combustion capture and the extent to which anything that’s not 100 per cent efficient is compatible with Net Zero.

He also was sceptical North Sea projects would get to the stage of capturing carbon at source – and it was “difficult to see on-rig capture and subsequent storage from flared methane as being viable.”

By contrast, electrification of on-rig infrastructure seemed “much more reasonable.”

Stuart Payne, director of HR and supply chain at the NSTA, confirmed the watchdog would make sure the practice achieved real progress.

He concluded: “The NSTA is working with industry leaders to ensure that as the sector delivers energy security and accelerates net zero technologies, we deliver real economic growth and real jobs across the whole spectrum of energy.”