Can a 60/40 split portfolio deliver better outcomes?

Recent decades have been a tumultuous time for investors. In the last 20 years alone we have experienced two of the biggest stock market crashes in history – the bursting of the dotcom bubble at the turn of the millennium and the financial crisis in 2008.

Smoothing returns and avoiding losses has been a crucial imperative for investors, which is why many have adopted the 60/40 rule.

In its simplest form, the 60/40 rule means having 60 per cent of your portfolio invested in potentially higher risk, historically higher return, assets such as stocks and the other 40 per cent invested in lower risk, but also traditionally lower return, assets such government bonds.

The theory is that a 60/40 portfolio should provide equity like returns while smoothing out the extreme highs and lows (volatility) that come with an equity only portfolio.

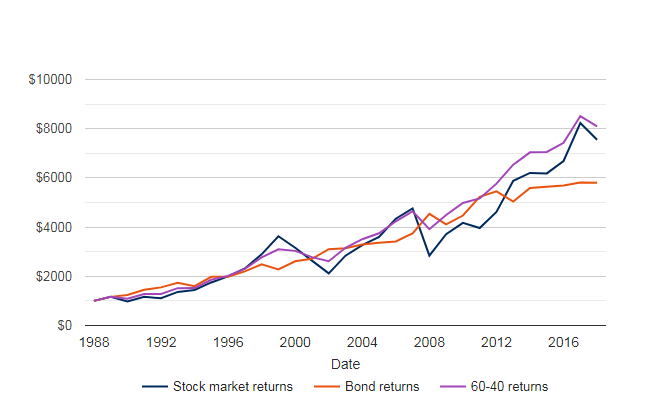

Schroders’ calculations show that investment, over the last 30 years, based on a 60/40 strategy, would have been effective both in terms of smoothing out volatility (the main aim) but also delivering a superior return.

A $1,000 investment made at the end of 1988, using three different approaches involving stocks, bonds and a 60/40 combination of the two, could have been expected to perform as follows:

- $1,000, 100 per cent invested in stocks now = $7,554. A return of 7.2 per cent a year.

- $1,000, 100 per cent invested in government bonds now = $5,806. An annual return of 6.2 per cent.

- $1,000, 60 per cent invested in stocks, 40 per cent in government bonds now = $8,091. An annual return of 7.5 per cent.

In the example, stocks are represented by the MSCI World Total Return Index (global developed markets) and bonds by the benchmark 10-year US Treasury bond. Returns have not been adjusted for inflation or trading costs.

Of course, past performance is not a guide to what investors can expect in the future.

How a 60/40 strategy could have provided better and smoother returns

Source: Schroders. Refinitiv data for the MSCI World Index – total return and benchmark 10-year US Treasury total return correct as at 31 March 2019. The material is not intended to provide advice of any kind. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy

Rebalancing: The secret to making the 60/40 rule work

To make the strategy work investors need to tweak their portfolio at least once a year, to ensure it retains its roughly 60/40 split. This action is known in investment circles as rebalancing. In practical terms, it involves selling some outperforming assets and re-investing the proceeds in the underperforming ones, so that the mix of stocks and bonds remains 60/40.

You need to do this because, for instance, if stocks have a good year and bonds have a bad one, equities could end up representing a far bigger percentage of your portfolio than 60 per cent. Left alone, you could unwittingly end up with a portfolio heavily weighted towards one asset. And that leaves you exposed to greater risk.

In this example, by selling outperforming stocks and buying underperforming bonds, the portfolio would again be balanced. In an ideal world, the underperforming assets would then begin to perform better, enhancing the total portfolio return, while also smoothing out volatility (extreme high and lows price moves).

Read more:

Does the 60/40 strategy still work?

Over the last decade a 60/40 portfolio could have returned 7.5 per cent annually. However, record low interest rates and other policy initiatives employed by central banks, (such aa quantitative easing – adding more money into the financial system) to aid economic recovery, after the financial crisis, have distorted returns. The overall effect was a reduction in the return on government bonds.

For instance, a bonds only investment, since 2008, would have returned just 2.5 per cent. This compares with a stocks only portfolio that would have returned 10.3 per cent.

The low interest rate environment, combined with central bank monetary policy, has kept bond yields artificially low and pushed investors into riskier assets, such as stocks, in a search for higher returns.

The 10-year US Treasury yield fell from 9.5 per cent in 1989 to 2.8 per cent in 2018. The current dividend yield for global stocks is 4 per cent. So an investor rebalancing a portfolio, selling outperforming stocks and buying underperforming bonds, isn’t seeing the level of returns that had been more usual historically.

Is there an argument for a different type of strategy?

Back in 2013, Warren Buffet, the billionaire investor and chief executive of the world’s largest financial services firm, Berkshire Hathaway, made waves. He said he was leaving instructions, that upon his passing, the trustees of the inheritance he leaves behind put 90 per cent of the money into stocks and 10 per cent into short-term government bonds.

Such a 90/10 strategy would certainly have paid off over the last decade. Since its low, in March 2009 during the financial crisis, the MSCI World index is up 242 per cent. But being so heavily invested in equities is a very risky strategy. Investors adopting it would have to have the constitution to endure the roller-coaster ride that being a stock market investor entails.

Claire Walsh, Schroders Personal Finance Director, said while the 60/40 rule may not have provided the returns investors may have desired in recent years it imbues them with investment discipline.

“As the data shows, the 60/40 rule could still achieve a decent return but since the introduction of low interest rates, from the time of the financial crisis, it has been less effective. However, there are still benefits in this approach.

“For instance, using the 60/40 rule and regularly rebalancing could prevent you from making classic investment errors, such as panic buying and euphoric selling. Much like saving on a monthly basis, regular rebalancing teaches you to be disciplined with your investing.

“Arguably the real benefit of the 60/40 rule is psychological. Fluctuating markets are distressing. Rebalancing can give investors greater peace of mind. It can help them avoid the temptation to fiddle too much with their investments and stop them from selling at the bottom (because things are bad) and buying at the top.”

- For more insights from Schroders visit their content hub and follow them on twitter.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.