Brits’ take home pay still falling rapidly despite record wage rises

Brits are suffering one of the sharpest hits to their take home pay despite businesses handing workers bumper pay prices, official figures out today reveal.

Real pay tumbled 2.6 per cent over the three months to November, among the steepest drops seen outside the Covid-19 crisis, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The huge drop in spending power comes despite regular and total pay including bonuses increasing 6.4 per cent, underscoring the strength of the current inflation surge gripping the UK economy.

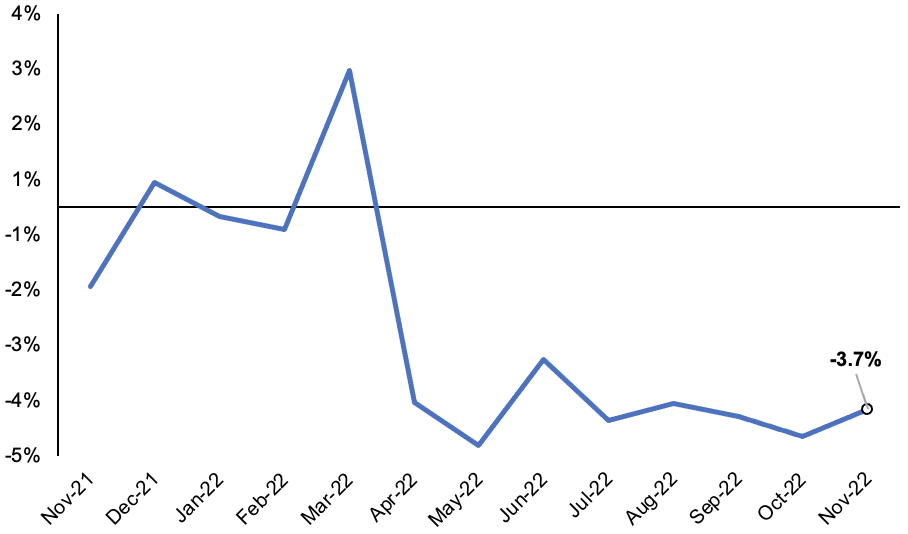

Isolating the monthly figures and using the consumer price index measure of inflation, real pay dropped by a larger 3.7 per cent. Living standards have now eroded for eight months in a row.

City bankers, insurers and brokers trousered the biggest pay rises over the last year, with their wages jumping more than seven per cent.

Inflation has raced to a 40-year high of 10.7 per cent, putting household finances in a vice.

The rate of price increases dropped from 11.1 per cent in October, leading economists to forecast it will gradually fall in 2023.

Although inflation will drop this year due to international energy prices coming off their record highs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, experts think households are on track to absorb the biggest hit to their take home pay ever.

Analysis by the economic think tank the Resolution Foundation earlier this month reckons living standards will have cumulatively dropped £2,100 over the course of a two year cost of living crisis.

Annual % changes in pay accounting for annual CPI inflation

Real incomes will not return to their pre-pandemic level until 2028, the organisation which focuses on low and middle income Brits said.

“The single best way to help people’s wages go further is to stick to our plan to halve inflation this year,” chancellor Jeremy Hunt said. He and prime minister Rishi Sunak’s promise to slash inflation was already forecast by the Bank of England to happen last November.

The ONS said the proportion of people without a job is rising. The unemployment rate nudged up 0.2 percentage points to 3.7 per cent in the three months to November.

Some 27,000 people secured a job over the same period, although this was cancelled out by a more 60,000 rise in people being made unemployed.

Businesses are reining in hiring campaigns in preparation for the UK economy tipping into recession.

Vacancies dropped 75,000 over the month to December, but they are still running at near record highs of more than 1.1m.

Although the labour market is showing signs of cooling, private sector pay growth topped seven per cent, likely due to businesses having to step up pay to attract and retain workers, posing problems for the Bank of England.

Governor Andrew Bailey and co are worried workers will chase rising prices by demanding bumper pay increases. That could incentivise businesses to hike prices to protect margins, raising the risk of a 1970s-style inflationary spiral emerging.

“The worry is that, if wage growth exceeds productivity gains, firms may seek to pass on some of these extra costs via future price increases, thereby prolonging the bout of inflation,” Sandra Horsfield, economist at Investec, said.

The Bank will announce its next interest rate decision on 2 February, with analysts divided over where they will sign off a 25 or 50 basis point hike.

“The latest labour market data maintain the pressure on the MPC to raise interest rates by another 50 basis point next month, rather than slow down,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

Bailey and co have raised borrowing costs nine times in a row to 3.5 per cent, a post-financial crisis high.

Economic inactivity – when people do not have a job and are not looking for one – edged lower, meaning people are returning to the jobs market, raising the likelihood of pay growth cooling.