Britain’s pro-growth agenda needs a rebrand to convince reluctant voters

As the Conservatives face the prospect of three brutal by-election losses, it needs to look at how it rebrands economic growth to voters obsessed with local issues like ULEZ, writes Adam Hawksbee.

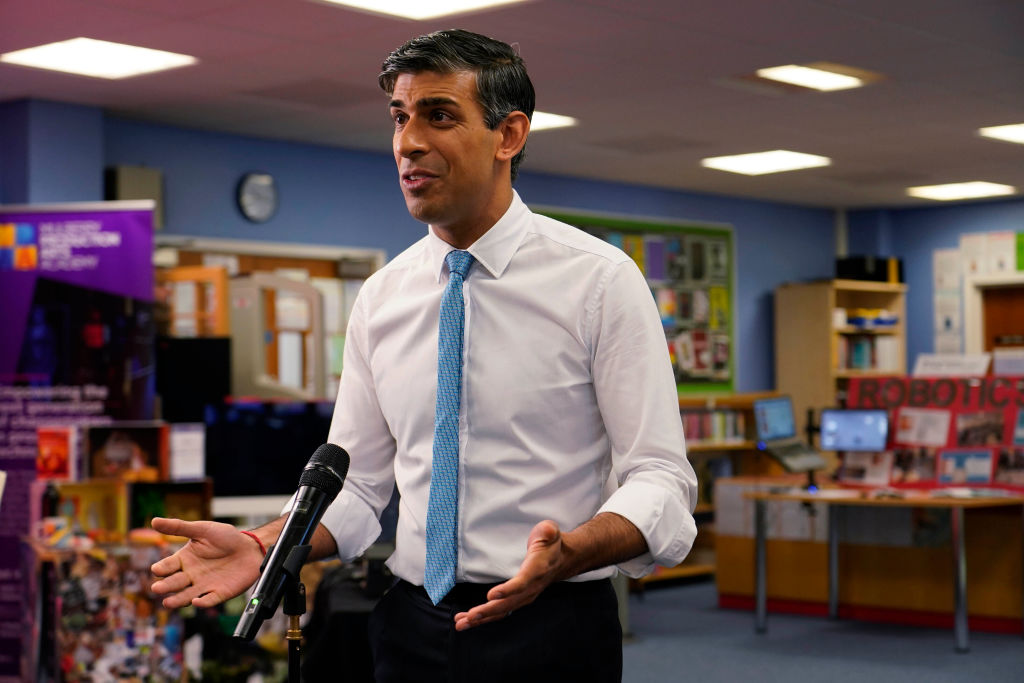

There is thankfully one thing that everyone in Westminster appears to agree on: growth. One of Rishi Sunak’s five pledges is to get the economy growing. Rachel Reeves has criticised the UK’s “high tax, low growth spiral”. Liz Truss launched her new Growth Commission last week, ostensibly to provide alternative economic forecasts to “doomsters” at the OBR.

But when it comes to making difficult policy decisions, growth often gets sidelined. The necessary steps on planning, regulation and investment are ducked or fudged. And all the while, the UK is getting left further behind: the average American could stop working on September 27 and they’d still be richer than the ordinary Brit. The country urgently needs a serious pro-growth consensus – and building it might mean abandoning the word “growth” altogether.

Part of the problem is that growth doesn’t cut through on the doorsteps. Thursday’s trio of by-elections will be more about the Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ) or local hospitals than flatlining productivity. And what little growth there has been in the economy hasn’t filtered through to rising wages or improved living standards – particularly for those on the lowest incomes or living in the most left-behind towns. When the economist Andy Haldane toured the country a few years after the 2008 financial crash, he heralded the economic recovery suggested by national data. Members of the public often asked him: “Whose recovery”?

This antipathy about growth among voters means there’s not enough support for MPs to take the necessary steps to turn things around: building more homes, investing in energy infrastructure, modernising regulation. And it opens space for dangerous degrowth ideas, like the Greens irrational opposition to nuclear energy, to begin permeating our politics, which will ultimately make us all poorer.

GDP doesn’t capture the most important element of growth: the identification, development, and dissemination of innovation, embedded in new goods and services. Markets allow investment to flow to the best ideas better than any planned system could. Growth is a byproduct – the goal is using market dynamics to solve our biggest problems. And right now, those problems are piling up.

The time is right to reframe the movement for growth. More than that: we need a new political and policy programme focused on ending our economic stagnation. At the end of last week, a hundred academics, entrepreneurs and policy thinkers gathered at a conference in Cambridge, put together by the organisation Civic Future, to articulate this new agenda. Conversations coalesced on a single concept: progress.

A movement for progress would have at its centre the discovery of solutions to humanity’s biggest challenges. How can we generate abundant clean energy? How do we treat or cure the diseases afflicting our ageing population? How might we build cities that make us happy and healthy? Progress means more than just moving frontiers forward – it requires a focus on ensuring everyone benefits from new technologies, by ensuring their costs come down and that wages go up.

Progress is already playing a big role in the US policy debate. Think tanks such as the Institute for Progress inform debates in Washington DC on reforming planning and streamlining science funding. Commentators have developed their own versions of the progress agenda: think of Ezra Klein’s “supply-side progressivism”, Derek Thompson’s “abundance agenda” or James Pethokoukis’s rejection of left or right wing politics in favour of “up-wing” ideas.

The UK is catching up. The journal Works in Progress serves as a hub for ideas to improve the world, while the Tony Blair Institute and my own think-tank, Onward, have launched science and technology programmes to reshape the Westminster debate. The creation of ARIA to focus on blue sky science projects and the establishment of a specific science department in Whitehall suggests that the British state is getting more serious about embracing progress.

What the movement for progress lacks is serious political impetus. We need nothing less than for people to fall back in love with the future, and take the difficult decisions that will unlock prosperity. That doesn’t mean being naive or boosterish – the public are right to have concerns with our current economic model. But we are never going to be able to take on the entrenched interest groups that defend barriers to progress unless our political class can clearly articulate the size of the prize.

At the end of an electoral cycle, amid a cost of living crisis, a new focus on progress might seem like a pipe dream. But without it, we’re going to remain stuck in the same permacrisis.