Britain passing up £18bn economic boost due to ‘failure’ to build enough homes

Britain is passing up on a near £18bn economic boost due to the government and businesses’ “failure to build enough new” homes, a former Tory housing minister has claimed today in a new report.

Brandon Lewis, ex-housing and planning minister, in a foreword to a report by think tank Policy Exchange said decades of weak housing supply has taken its toll on families “in the form of higher house prices, higher rents and higher monthly mortgage repayments”.

Delivering an extra 100,000 homes each year could grow the UK economy by £17.7bn and make the “British dream” of homeownership a closer reality, he added.

Gross domestic product would receive benefits beyond greater construction output, the report said, via stronger productivity gains funded by more evenly distributed investment and higher employment.

Under the 2019 Conservative election manifesto, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak must deliver an additional 300,000 new homes each year by the middle of the current decade. He is poised to miss that goal.

A shortage of homes in the UK has put upward pressure on house prices for years, pricing potential buyers – often younger people with relatively lower deposits – out of the market.

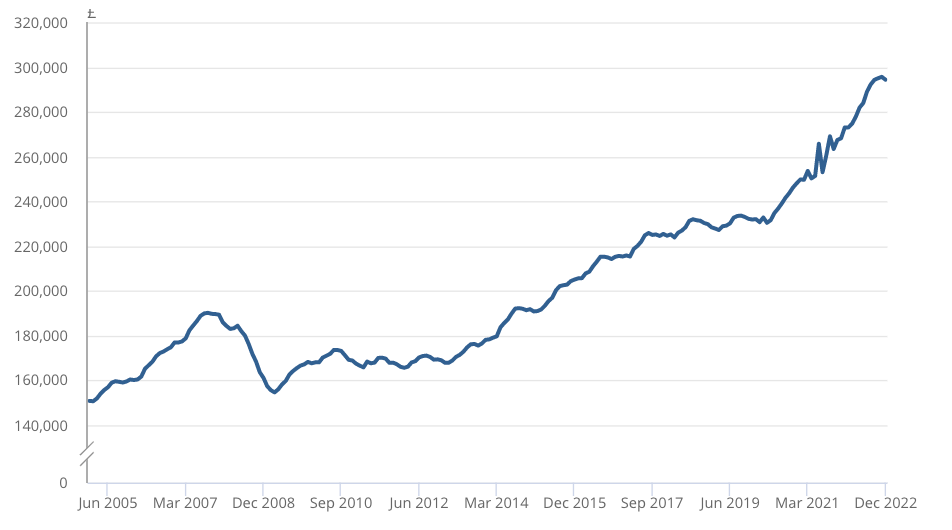

Over the last decade, UK house prices have climbed 74 per cent, according to the Office for National Statistics, up to £294,328 from £168,842.

In London, they’ve increased to £543,098 from £313,744 over the same period.

According to data provider Moneyfacts, rates on a typical 2-year and 5-year mortgage have more than doubled over the last year, squeezing affordability.

House prices have rocketed since the mid noughties

“Deep uncertainty about the availability of land for residential use” has squeezed new housing production for years, Policy Exchange said, and incentivised big house builders to hoard land that could have been used by smaller builders to produce homes at a lower cost.

The shortage of social housing has also impacted housing costs. The stock of housing owned by councils dramatically decreased since the 1980s, mainly because the introduction of the Right to Buy policy wasn’t matched by an increment in building council homes. Scores of council-owned flats entered the private market as tenants started to buy them – and are now in the hands of private landlords.

As a consequence, the waiting list for social housing shot up. It stood at 1.19 million people in 2021, with 86,000 households in temporary accommodation, according to the report.

Temporary housing in England has often been reported to be inappropriate for the needs of the tenants or very poor quality. Those who are unable to access social housing enter the private rental sector; this pushes up demand, ultimately impacting housing costs.

The report highlights how historically, in the UK, the periods when the general housing stock was catering properly to the needs of the market always came hand in hand with an uptake in building social housing.

In 1975 local authorities and housing associations contributed 52 per cent of net new dwellings: in 2019, they made up just 19.6 per cent of new builds, according to Policy Exchange.

Building social housing must be considered a key part of the project if we want to make a dent in the housing crisis, the think tank said. To facilitate this, the government should accelerate the release of public land available for builders, and councils should be granted a more active decision-making role, collaborating with developers on joint ventures.