Britain needs Multinational Monday – not yet more arbitrary tax hikes

BRITAIN has just celebrated “Small Business Saturday”. Perhaps yesterday should have been declared “Multinational Monday”. Multinationals are often the engine of poverty reduction in under-developed countries; and they promote technology transfer and transform lives all around the world. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine what life would be like without them.

Of course, multinationals deserve moral censure when they behave unethically or are involved in cartel-like behaviour. However, we are in danger of creating a culture in the UK which is anti-multinational, anti-wealth and anti-bank, and the government is part of this problem.

Among a myriad of tax measures in the Autumn Statement, two stick out. The first is the tax proposals in relation to banks, and the second the so-called “Google tax”.

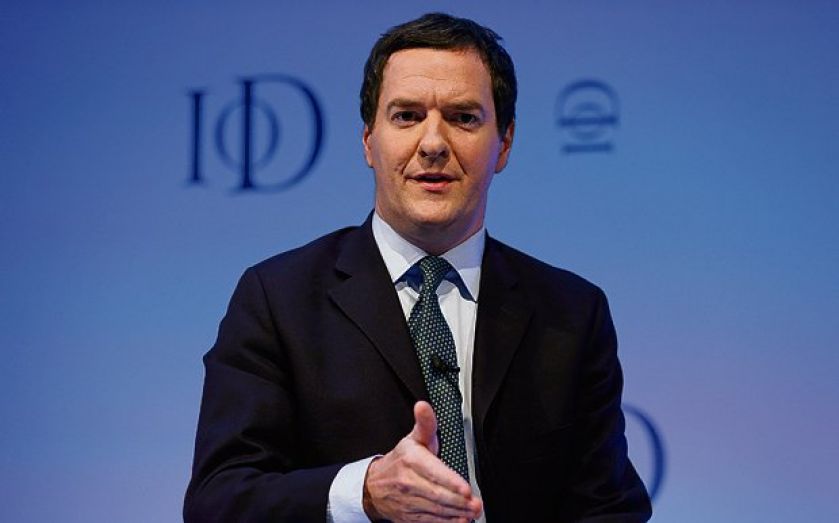

George Osborne’s bank tax announcement – that established banks will be restricted from fully offsetting losses since the financial crisis against their future profits when calculating corporation tax – is just one in a long line of tax measures that are counter to the rule of law or, at the very least, create dangerous policy uncertainty, thereby undermining Britain as an attractive place to do business. The basic principle of the corporation tax system is that profits over the long term should be taxed. This means that losses in one year should be offset against profits in another: to do otherwise would be to penalise firms that had volatile profits.

To restrict the extent to which losses can be offset against profits is bad enough. To single out four or five businesses is an abuse of government power. Arbitrary and retrospective changes to corporation tax are likely to make it more difficult for banks to accumulate capital, will raise the return that banks want on their capital, and will reduce the level of bank lending. The changes are also expected to increase the government’s current tax take, while reducing receipts a few years hence. This is an imprudent way to run fiscal policy.

The other measure is a proposed additional tax on profits diverted from the UK to low-tax jurisdictions. More detail about this is expected in the coming days. However, on face value, it is difficult to know what it could achieve. Currently, if profits are diverted according to the agreed international principles by which our tax system operates, then no tax is due in the UK; if they are diverted by other means, tax would be due. Insofar as these things are subjective, HMRC can dispute the matter, using the courts if necessary. How will the new approach differ?

We do need a new corporate tax system. We should move back to taxing a company’s owners directly according to their own tax position, rather than taxing a company in the country in which it is purported to earn its profits.

Meanwhile, we need stability. The bank tax is designed to raise serious money – though at the expense of revenue that will not be raised in the 2020s. The fact that the “Google tax” is only expected to raise £300m a year suggests that it is just political posturing. In other words, the government is promoting the impression of instability in the tax system, and trying to create a climate that is hostile to big business, simply to improve its standing in the polls. In the long term, such approaches are bad for Britain’s prosperity and bad for any party that wishes to garner votes on a pro-business, pro-prosperity ticket.