Boris Johnson’s calorie labelling plan is well-intentioned but economically inept

Let me start with a concession to the Prime Minister: not all the policies in his anti-obesity drive are outright objectionable.

Banning food advertising and telling shopkeepers where they can and can’t stock their products are obvious and unacceptable intrusions, whatever their intended goal. But as a liberal economist, I am prepared to consider some of the other “nanny state” policies Boris Johnson has announced today through the lens of conventional economics.

People may not always realise how many calories are in their favourite foods and drinks, and this may lead them to over-consume. To put it in economic terms, there is asymmetrical information. The seller knows something important about the product that the buyer doesn’t.

Most packaged food in Britain is labelled with calorie information as a result of a voluntary agreement with the food industry. The government now wants to extend this to alcoholic beverages and the out-of-home food sector.

In principle, there is nothing wrong with this. Calorie labelling is good for the same reason advertising bans are bad: both labels and adverts provide information. The more information we have, the better we can align our purchases with our preferences.

Nevertheless, labelling is unlikely to be a solution to obesity, and the unintended consequences may outweigh the benefits.

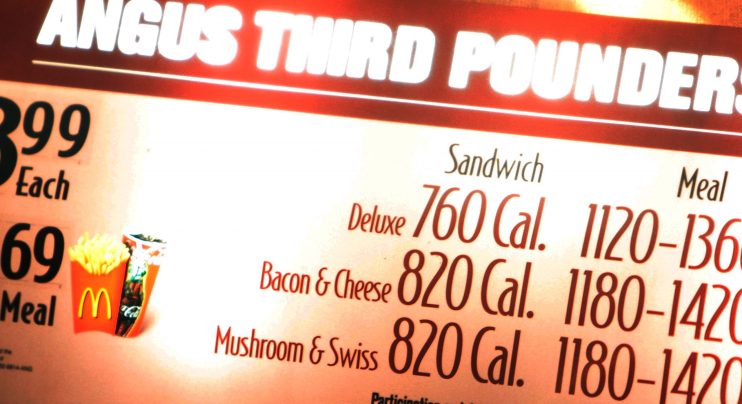

First, there are the practical problems for pubs and restaurants. It is easy enough for Burger King and Starbucks to display calorie counts because they have standard menus that only occasionally change. It is more difficult for smaller food outlets.

True, the new rules are initially only set to apply to food companies with more than 250 employees, but we all know how the scope for these kinds of policies can creep, and besides, even chain restaurants sometimes like to vary their menus. Will it be worth serving up a dish of the day if its energy content has to be scientifically analysed first? Will chefs be able to guarantee that every portion contains exactly the same number of calories?

Having perfect information about the food we eat is a nice idea, but it seems wholly impractical in this instance.

More importantly, labelling doesn’t actually seem to have much of an effect on consumer behaviour.

After New York City introduced mandatory calorie labelling in fast food restaurants in 2008, studies of this natural experiment found that it had no effect on the number of calories purchased by children or adults. Field experiments have also found no effect from out-of-home food labelling.

It is not that diners don’t take in the information. They just don’t appear to care.

The same seems to be true of alcohol. In 2018, a behavioural experiment found that drinkers who were given calorie information drank much the same as those who were not. Incidentally, the same was true of people who were told how many units of alcohol were in the drinks.

Sadly, a total lack of efficacy has never been a barrier to anti-obesity policies in the past, so the “public health” lobby can probably live with this. More interesting are the possible unintended consequences. The mental health implications for people with or at risk of eating disorders being bombarded with information designed to nudge them to watch their calorie intake does not appear to have been discussed.

And there’s another consideration. Although no empirical research has looked at the issue, there are plausible concerns that weight conscious individuals — young women in particular — will respond to calorie counts on alcohol by eating less before they go out or by switching to spirits. A vodka and slimline tonic contains around 70 calories whereas a pint of beer has over 200, but slamming back the vodka is not necessarily going to lead to the best health outcomes.

If some people switch to hard liquor because they are better informed about the energy content of their drinks, that will be a perfectly rational response. At the margins, it might even have some effect on obesity.

It won’t be the kind of behavioural change that health campaigners want to see, but humans are rarely as predictable as they think.

Main image credit: Getty