Boris Johnson’s political headache isn’t over as the threat to the Union rears its head again

Boris Johnson has often been both the Houdini and the Heineken politician over the past decade. But if he survives the latest party-gate scandal he may unwittingly walk into a much bigger domestic political headache, with more than just his career on the line – the future of the union.

Of course he will do everything to kick the issue of a second Scottish referendum on independence into the long grass. Lose and he will not only have to resign; he will also go down in history as the Prime Minister who oversaw the break up of the union. Johnson could end up being the PM who took the UK out of Europe and then England out of the UK.

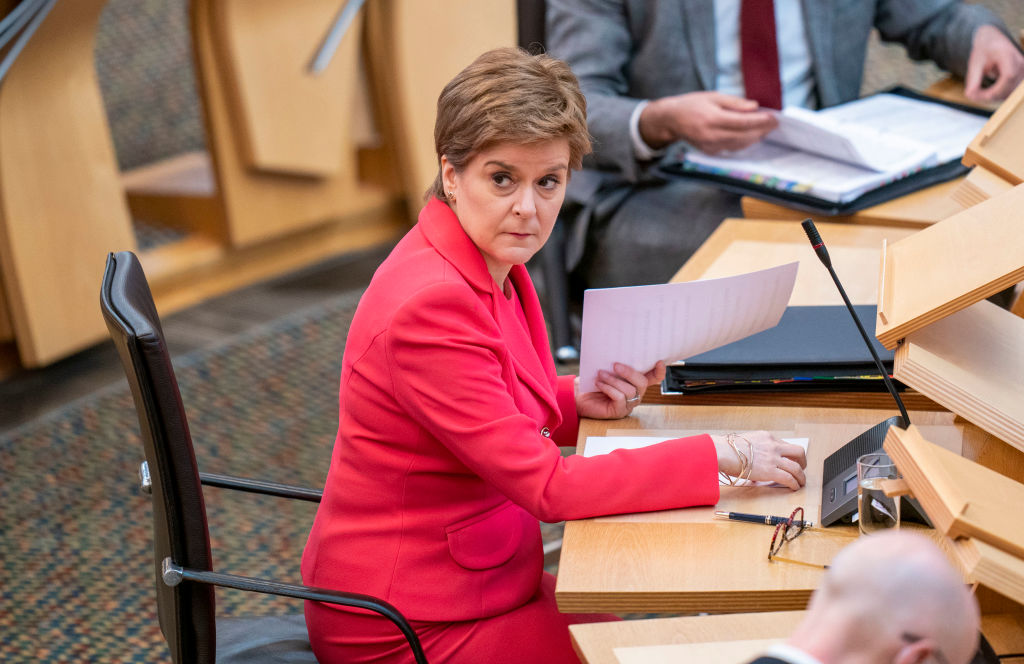

Covid-19 gave devolved nations a taste of greater independence – with Nicola Sturgeon, Mark Drakeford and the former First Minister of Northern Ireland Arlene Foster stepping into significant leadership roles as they forged an often different path in the fight against the pandemic.

Despite constant assurances from Johnson that the devolved nations were working together on Covid-19 restrictions, there were divergent measures on masks, on social gatherings, and even on border controls. Sturgeon and Drakeford banned people from England travelling across the Scottish and Welsh borders at some points.

The pandemic might have put the brakes on IndyRef2 campaign temporarily, but in the eyes of many, it has strengthened the cause and motivation by giving their leaders the opportunity to show what it would look like if they held the reins.

Northern Ireland is still awaiting the final Brexit settlement and depending on how that nets out it could have huge ramifications for their place in the union. And while the Tories still have strong representation in Wales, a majority of those seats came in 2019, and without a prospering Boris Johnson they might disappear as quickly as they came.

It is much harder to reel in this newfound sense of independence, putting the future of the union firmly back on the political map. In his charge as head of the union unit last summer, Michael Gove promised not to stand in the way of another Scottish independence vote if it is clearly the “settled will of the Scottish people” to have one.

One important lesson learnt from the Brexit referendum is that it is very difficult to turn the tide in a short period of time.

We need an external group that is constantly campaigning for the Union and holding the likes of the SNP and Plaid Cymru to account. Despite being a very accomplished politician, Sturgeon has a woeful record in office. Crime has soared, drug deaths have tripled and NHS targets routinely missed. Yet she is rarely challenged over a litany of broken promises and instead lauded for what in Scotland has been seen as a more capable handling of the pandemic.

The Tories are too polarising to take on the role of heading up an external campaign group. Labour have equally struggled to incorporate the union into their political mission. And the Lib Dems remain in the political wilderness, not the force they once were.

The Republicans artfully used the campaign group America’s Rising to their advantage in the 2016 Presidential Elections producing opposition research on Hilary Clinton. They were famously behind her email saga revealing the politically damaging allegations that she used a private server for official government communication. These claims dogged her right up to polling day and played into the issue of trust.

If business groups, politicians and activists are serious about saving the union, they need to be putting together a cross-party group before the starting gun goes off.

Businesses dislike uncertainty – so the perceived precariousness of the union creates challenges for companies and will of course make foreign investors jittery. Given the relentless disruption over the past five years, the last thing the economy needs is the spectre of another referendum that will polarise the country.