Bitcoin highlights the opportunity for sustainable data processing

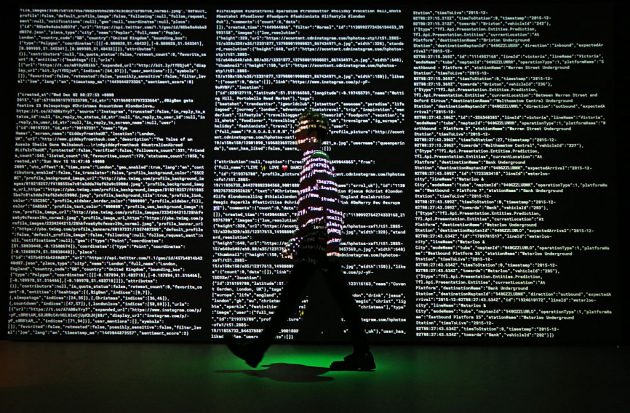

The price of Bitcoin is not the only thing that is surging. According to an analysis by Cambridge University and reported on by BBC News, the computer processing power that is now required to “mine” the cryptocurrency is 126.35 terawatt-hours each year. Or put another way: if Bitcoin was a country, it would be in the top 30 energy users worldwide, according to Michel Rauchs from The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

The emergence of cryptocurrency into the mainstream is challenging what had long been the sovereign monopoly of Governments over the right to issue currency and therefore to fully control their monetary policy. This dismantling of long-standing monetary practices in order to make way for new innovation is the kind of Schumpter-esque ‘creative destruction’ that some might label as the harsh-but-essential driving force of modern capitalism.

Similar trends of technology-driven creative destruction have led many to speculate upon the seeming inevitability of the displacement of many white-collar jobs as artificial intelligence and automation replaces humans. Voices advocating for universal basic income (‘UBI’) have grown louder in response, arguing that populations should be able to mitigate the financial insecurity of accelerating technological disruption. A privately funded project in California recently added further credence to the idea when it found that UBI helped to increase overall employment and also enhanced emotional wellbeing.

This notion that the accelerating technological progress of humanity is an opportunity to re-examine how we collectively manage and order economies and societies is nothing new. In 2016 Elon Musk said that robots will push us towards universal basic income. In 2017 Bill Gates called for a tax on robots to slow the spread of automation and to help to fund other types of employment. Gates proposed that a tax on robots could finance jobs taking care of elderly people or working with kids in schools, to which humans are particularly well suited.

In 2017 the European Parliament also called for, but then rejected, a ‘robot tax’. And since then other prominent technologists have proposed that a tax on artificial intelligence itself could help to reduce in-country and intra-country inequalities. One UK technology investor has blogged that a solution could be a tax on the acreage of the data centres which are powering the Internet of Things (IoT), and that this would also disincentivise ‘invisible’ energy use and the CO2 emissions which occur through the heavy use of data.

On the surface the ‘taxing data centres’ argument makes sense for a future world where almost everything will be connected by the cloud to the IoT, especially when considering the environmental impact of ‘invisible’ energy use. The applications that we demand from technology are becoming more and more data intense and growing exponentially. Training a single artificial intelligence model can emit as much carbon as five cars do in their lifetime.

What we may need is a system that jointly incentivises the redistribution of the benefits of technology whilst also creating an incentive for technology companies to mitigate the environmental impact of the energy that is required to power their data processing. Content providers such as YouTube could help the planet by throwing out more digital waste. In 2011 Google revealed that streaming 1-minute of video on YouTube consumes 0.0002 KwH of energy. A quick calculation reveals that the 2-minute ‘Baby Shark’ video on YouTube – which has accrued 8 billion views and become infamous amongst parents – has consumed enough energy to power 1,032 UK homes for an entire year.

Yet we cannot ignore the fact that the vast increases in the processing power needed for omnipresent technological applications is also what is helping to drive global reductions in extreme poverty. Technology transfer is generating new wealth and spreading it across nations. World Bank data even suggests that between 1988 and 2008 we may have seen the first decline in global inequality between nations since the Industrial Revolution.

Moreover, during the last decade, the renewable energy learning curve has flattened and, in most places, power from ‘new’ renewable energy sites is now cheaper than power from ‘new’ fossil-fuel powered facilities. The price difference between expensive fossil fuels and cheap renewables is growing annually. By 2030 over 50 billion devices will be connected to the Internet of Things and enabling new technological advancements. And thanks to the flattening of the renewable energy learning curve, there is a very real prospect that the step up in the processing power that is needed could also be environmentally sustainable.

This could also be an opportunity for developing countries. The industrial revolution saw Britain find prosperity by becoming the manufacturing powerhouse of the world. The late twentieth century saw China lift hundreds of millions out of poverty by doing the same. Perhaps then in the future, the world’s developing nations could prosper by building the world’s data centres and running them on cheap renewable energy? It is not such an outlandish proposition since technology transfer is already proven to stimulate growth.

The opportunity ahead is therefore clear. Huge and exponentially increasing demand for data processing will be a constant in a world where worldwide computer processing for Bitcoin mining alone is consuming more energy each year than Argentina. The challenge is whether we can unlock data-driven and human-improving applications such as artificial intelligence and robotics without undermining the stability of our well-ordered societies or damaging the planet. Based on current trends, there are reasons to be optimistic.