Best of 2022: Sir Craig Reedie lifts the lid on how London 2012 Olympics was delivered

In this interview from July 2022, Sir Craig Reedie, one of the architects of the London 2012 Olympics and one of Britain’s most influential sports administrators, looks back on the Games 10 years on.

If you lived through the London 2012 Olympics then you will probably remember where you were for its most spectacular or poignant moments – Super Saturday, Danny Boyle’s vivid opening ceremony, Andy Murray winning tennis gold – and Sir Craig Reedie is no different.

But while the former chairman of the British Olympic Association, one of the key figures in bringing the Games to the capital, had a front-row seat for most of that golden 17 days which began a decade ago this week there was one highlight that he missed: Usain Bolt’s 100m final.

Reedie had been due to be in the stadium in his capacity as a member of both the London organising committee (Locog) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) but stepped in to present fencing medals at the ExCel when a colleague was forced to drop out.

“I went to help the IOC and there was a protest and it went on and on. It became clear that I wasn’t going to get back to the stadium in time,” he recalls. “So we went back to the car but found that our television set had broken down. I think I was the only person in the world who didn’t see the 100m final as it happened.”

It is one of few regrets that Reedie harbours about that time and the £9bn London 2012 project as a whole, which he staunchly defends as both a success and good value for money as the 10-year anniversary provokes a bout of national introspection.

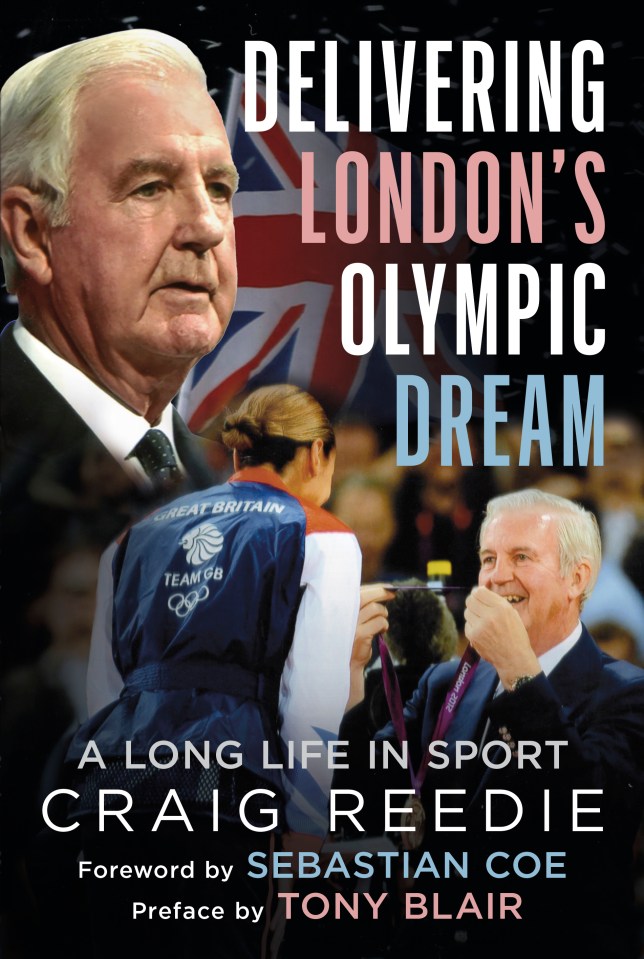

The Scot is one of the very few to have played a key role in the planning and execution of those Games, which he recounts in his new book Delivering London’s Olympic Dream.

An early breakthrough came in 1994, more than a decade before the final vote would be taken, when he established through some unofficial canvassing that his fellow IOC members would look kindly on a bid from the capital. “That was the easy bit. Thereafter it’s complicated,” he says.

While the creation of the Greater London Authority and the support of the late Dame Tessa Jowell greased the political wheels, Reedie and the BOA had to overcome the hijacking of Wembley’s rebuild by football and bad blood in the athletics world caused by the UK pulling out of hosting the 2005 World Championships. “That wasn’t the best background, I can tell you.”

Reedie, bid chief Sir Keith Mills and future chair Lord Coe went on a charm offensive. “The IOC like to give the Games to people they like. So we went out of our way to be liked,” he says. Up against the highly fancied Paris, London sought to emphasise its sporting credentials by taking an athlete along to each presentation.

Star quality of another kind also proved persuasive. “The turning point was the night that the IOC’s evaluation commission came into town and had their dinner at Buckingham Palace with the royals and whatnot,” Reedie says. “That went so well that suddenly people began to think ‘hey, this is serious’. And we pulled it off.”

Reedie, Coe and others celebrated long into the night after the vote in Singapore on 6 July 2005 but the jubilation was halted abruptly the very next day by the 7/7 bombings. He emerged from IOC meetings, unaware of the extent of the devastation, into a media scrum. “I fought my way through, went into an IOC office, looked at the television and thought ‘Oh my God’.”

Organising London 2012 was, nevertheless, “more routine than bidding for it”, he says. Tony Blair’s Labour government offered an early helping hand by footing the £400m bill for laying power cables at the site of the future Olympic Park. “You begin to get a warm feeling that you’ve got a decent partnership here if that’s the first thing that happens.”

Why Reedie believes London 2012 was a big success

“Of course there were arguments, small ones, but at the end of the day it came together,” adds Reedie, who praises Locog chief Baron Deighton for quickly solving any problems, such as G4S failing to provide its promised number of security staff. “Everybody said it was a disaster. It took Paul Deighton about a weekend to sort it out. The army were brought in; that was a big one.”

Although he missed Bolt successfully defending his Olympic 100m crown, Reedie has no shortage of highlights from London 2012, such as presenting gold medals to Katherine Grainger and Jess Ennis, and racing to Wimbledon to catch the end of compatriot Murray winning what was then the biggest title of his career.

He considers it all a huge success. “We won medal after medal after medal, which made people feel happy. And secondly we filled the stadiums, and that was a complicated ticketing exercise that worked very well [raising £770m], and then had the wonderful knock-on effect because of the ballot system of selling out the Paralympic Games as well.”

Reedie insists the “hard legacy” represents value for money, when new facilities, housing and jobs – along with related developments such as Westfield Stratford – are taken into account. “The housing, you could argue about the shape and use of it afterwards.” But, he says: “We took the most awful part of London and we cleaned it up and turned it into a magic place.”

London 2012 has not, however, led to the boom in exercise promised by its strapline “Inspire a Generation”. “People have said not enough people took up sport afterwards. The answer is, with respect, our job was to run the Games, not to look after the promotion of sport in the country for time immemorial,” says Reedie.

Nonetheless, some aspects of the Games have been tainted. Team GB won 29 gold medals, behind only the USA and China. It proved the zenith of UK Sport’s controversial “no compromise” strategy, which has since been cast in a different light a host of welfare scandals and ethically dubious practices, most notably in gymnastics and cycling.

And painfully for Reedie, who later as president of the World Anti-Doping Agency dealt with Russia’s systematic cheating, it turned out to be far from “the cleanest Olympics ever”, as some had pledged. “I was furious. But at the end of the day, me being furious doesn’t do away entirely with the good London 2012 did for athletes and for this country.”

He concludes: “I can make a case for it in every way – the political unity, the skill, care and hard work of delivering a very complex project. I can also make a case for its economic impact, all the construction work, the business that came to Britain – all of that made sense. There is a soft benefit which is impossible to put a value on, but it has a value.”

London 2012 also re-established Britain as a destination for major sporting events. Since then the UK has hosted the Commonwealth Games, World Athletics Championships, cricket and rugby World Cups, the bulk of a men’s football European Championship and is reaching the crescendo of the women’s version.

There has even been talk of bringing the Olympics back in 2036 or 2040, but Reedie is sceptical about the chances of success, at least while the political stability that helped so much in winning and then delivering London 2012 remains absent.

“I think there is some UK Sport committee quietly thinking about it, but it’s no more than that. And to the best of my knowledge no one has been anywhere near the IOC. I would expect to be pushing up the daisies for quite a long time before that happened.”

‘Delivering London’s Olympic Dream: A Long Life in Sport – Highlights and Crises’ By Sir Craig Reedie was published by Fonthill Media on 7 July 2022. https://www.fonthill.media/