Best of 2022: How Games Workshop founder Ian Livingstone created a £3bn giant

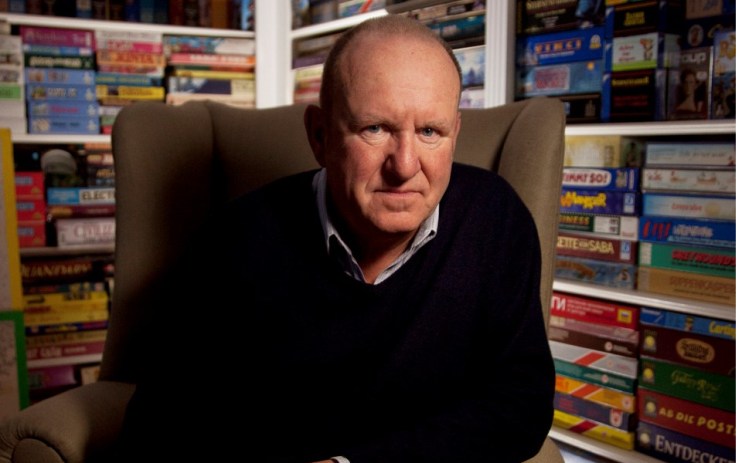

In a leafy enclave of West London, Ian Livingstone is balanced precariously upon a chair in his study, grasping for a top-shelf box filled with incredibly rare figurines.

The legs of the chair creak in protest, and there is a moment when I fear I may be responsible for the untimely death of the man who helped introduce the world to such treasures as Warhammer, Tomb Raider and Dungeons & Dragons. A life-size Lara Croft, surrounded on all sides by stacks of board games, looks on disapprovingly.

“It’s been quite a year,” he chuckles once he’s safely returned to terra firma. This is an epic understatement – the day before we met he was at Windsor Castle being knighted for services to video games. The following day his new book, Dice Men, hit the shelves, following hot on the heels of a new entry into his Fighting Fantasy series, 40 years after the first one was published. It’s also exactly four decades since he opened the first Games Workshop store alongside his old school friend Steve Jackson.

He and Jackson left Games Workshop in 1991 after they and fellow stakeholders Keith Pinfold and Bryan Ansell cashed in their shares for a reported £10m. It would go on to float on the stock exchange, its market cap peaking in 2020 at £3.3bn – more than that of Marks & Spencer and ITV.

Dice Men is the story of the early days of Games Workshop, a time when Livingstone and Jackson slept in a camper van and rented office space at the back of an estate agent. It’s a wonderfully nostalgic piece of work, part memoir, part full-colour scrapbook, told with infectious enthusiasm and delivered with the pacing you would expect from an international best-selling author.

It’s full of amazing little nuggets that seem too far-fetched to be true: how Richard Branson once tried to buy Games Workshop; how Livingstone once developed an (unsuccessful) board game with Andrew Lloyd Webber; how, during the ‘satanic panic’ of the 1980s, a woman claimed she saw her son levitate while he was reading one of Livingstone’s fantasy books.

It’s also wonderfully evocative of a bygone era: pictures of smoky old offices painted in dull oranges and browns; typewritten letters covered with hand-drawn scrawls.

We settle into a pair of armchairs as Livingstone is telling me how he got his big break, when the American creator of Dungeons & Dragons somehow got ahold of his fanzine, Owl & Weasel, which had a circulation of just 50 copies.

The spectacularly-named Gary Gygax was without a European distributor for his new game – so Livingstone and Jackson quit the lease on their £10-a-week Shepherd’s Bush flat and flew to meet him in Geneva, Wisconsin, returning with the sole European distribution rights to what would soon become a global phenomena.

“When we came home we had nowhere to live and nowhere to operate from – but we got by,” says Livingstone.

I wonder if this kind of bedroom entrepreneurialism is dying out amid the soaring cost of rent and education – could Games Workshop happen today?

“If you’re driven enough you will find a way,” he says. “When you’re driven by passion, you don’t see the hardship. It’s not exactly living the dream but I’d much rather do what we did than do a much better paid job where you don’t get the satisfaction. It was our passion that got us over the line. We were games players, so work and play were the same thing.”

Still, the level of their success is mind boggling. How would a young Ian have reacted if someone had told him the company he was running out of a van would one day be worth billions?

“I’d have said you’re having a laugh, aren’t you! It’s unbelievable – but we didn’t do it to make money, we had no vision of what it might become, we just wanted to turn our hobby into a business and determine our own destiny. We wanted to make and import the games we wanted to play and we were delighted that other people wanted to play them too.”

So no regrets?

“No regrets. If you use the analogy of being parents, Steve and I sold out in 1991 and the baby grew up and became a very successful child and we watch on from the sidelines as proud parents. I feel a huge sense of pride that we created this great British success story.”

Still, he must wish he’d held onto just one percent of that stock…

“You can always think like that but it’s best to just move on.”

Reading Dice Men, you could be forgiven for thinking the story of Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson is one defined by good fortune, a tale of chaos being somehow transmuted into gold. But lightning didn’t just strike once for Livingstone – it struck again and again, until it couldn’t possibly have been down to dumb luck, rather the result of a serious business mind.

While at Games Workshop a chance meeting at a games convention with a publisher from Penguin led to the first Fighting Fantasy novel (another joint venture with Jackson), a spin on the choose-your-own-adventure format that saw players rolling dice as they battled goblins and wizards on epic journeys. The franchise went on to sell more than 20m copies, several of which ended up in my teenage bedroom.

After leaving Games Workshop, Livingstone took a role as chairman of Eidos, helping to launch global hits including Tomb Raider. He published a report for Ed Vaizey about improving coding skills in schools. Now he’s involved in his own freeschool, the Livingstone Academy in Bournemouth, which promotes games-based learning.

“When you play a game, it’s digital making,” he says. “In Rollercoaster Tycoon you learn about physics when you build the rides, and you learn about management when you hire staff.”

Given all his experience from the years since he started out, what would he do differently? “Definitely get funding in,” he says without a pause. “We were turned down by the bank – and in the bank’s defence we were not investor-ready. We went in with an enthusiasm for Dungeons & Dragons and little else. It’s important to have a good business partner alongside the creative team, allowing each other to be successful. Don’t be afraid of failure but fail fast and move on.”

Anything else?

“Hang onto your IP. My whole life has been trying to hang onto intellectual property. With D&D we had a three year deal, at the end of which Gary Gygax wanted to merge the two companies. We said no and we lost the deal, and that’s when we realised we were vulnerable.

“So we started to publish our own games like Talisman and Battlecars and Warhammer. After Warhammer, the whole company was built around that IP – the publications and the miniatures and the stores, all making value from the same IP.”

Surely now, after more than 50 years of grind, he’s finally slowing down?

“No, no. I’m 72-years-old now and I’m never going to retire. I’m probably working more than ever. I’m a partner at Hiro Capital, trying to help the next generation of games-makers. I have plans for another book, I have my school… I think success is soon forgotten but ambition lasts.”

Rather adorably, after all these years, he and Jackson still play board games together once a week, usually over Zoom but sometimes in person; the same group of five have been playing since the 80s – right now they’re into a game called Splendor.

“I’m secretary of the Games Night Club, for which I have published 604 issues of the newsletter to a circulation of six people,” he says.

Who usually wins?

“We have a cup at the end of each year – I’ve won it the most but this year I’m trailing to games developer Peter Molyneux.”

He leads me out through his wonderland of memorabilia. Spread over several rooms, there are long-since out of production Warhammer miniatures; an entire wall filled with the original paintings for the covers to his Fighting Fantasy books and board games; Guinness adverts alongside the original artist sketches, part of what used to be the biggest collection of Guinness art in the world (most of it now sold); a signed Manchester City jersey from the days when his video game company Eidos was the club sponsor; a working pinball table.

I wonder if there’s one treasure he values ahead of the rest – one thing he would run back in for should the house catch fire.

“Oh no! That’s impossible,” he groans, putting his head in his hands. “That’s like saying which child would I save!”

He thinks for a minute, apparently taking this doomsday scenario very seriously. “OK, I have an unopened, shrink-wrapped 1975 Dungeons & Dragons boxed set, so I think I’d have to reach for that.

“But I’d also consider grabbing my first handwritten manuscript for The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. I’ve kept all of my manuscripts, the first 10 of which are handwritten in pen and ink. My girlfriend of the time typed them all up.”

Should his house really catch fire, I hope he doesn’t run back in at all, because Ian Livingstone is a national treasure himself, the kind of creative mind that only comes around once or twice a generation. Get yourself a copy of Dice Men and you’ll see what I mean.

• Dice Men by Ian Livingstone is out now, published by Unbound, priced £30