Bank of England to surpass Federal Reserve and hike interest rates to 15-year high

The Bank of England will have to hike interest rates to their highest level in more than 15 years to tackle sticky inflation that will stay above its target for at least another three years, a top Wall Street investment bank has warned today.

Researchers at Goldman Sachs suspect businesses will carry on passing on strong wage and cost increases for the next couple of years, keeping inflation above the Bank’s two per cent target until 2026.

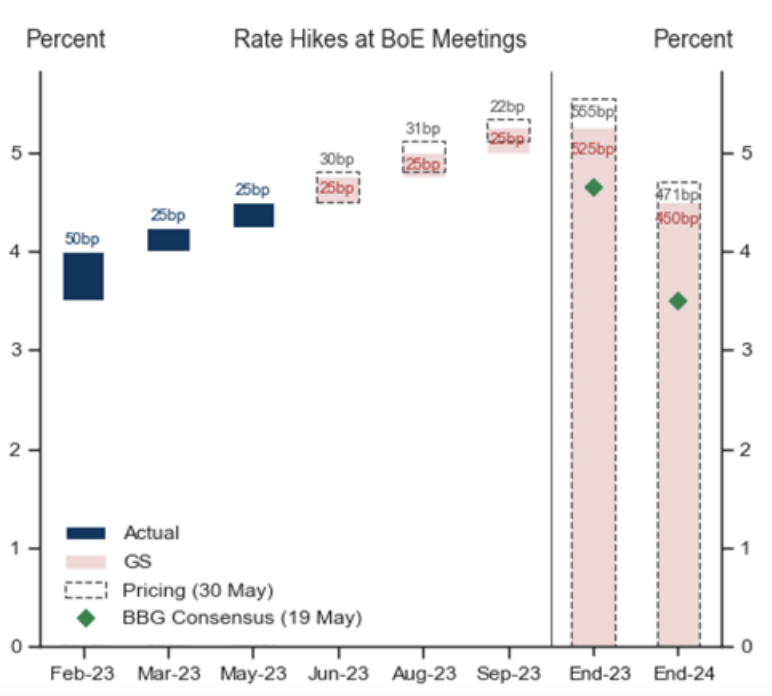

As a result, Bank Governor Andrew Bailey and co are set to bump borrowing costs up three more times this year to 5.25 per cent, which would be their highest level since February 2008. Just 75 basis points worth of cuts will come in 2024, Goldman reckon.

That would mean the Bank would have raised interest rates 15 times in a row since December 2021, among the most aggressive and longest tightening cycles in the central bank’s history and certainly the strictest since its independence in 1997.

Such an upward move would also mean the Bank would likely surpass the US Federal Reserve in its tightening cycle.

The Fed has taken borrowing costs to a range of five per cent and 5.25 per cent and is tipped to stop raising them at its next meeting next month.

“Our analysis agrees with recent BoE estimates that high headline inflation has been the primary driver of strong wage growth—as workers bargain to regain their level of real income prior to the war in Ukraine,” Goldman’s analysts said in a note to clients last night.

An exodus of workers from the jobs market alongside high nominal wage increases have prompted employers to step up starting pay to find new staff.

Sky high inflation has been eroding workers’ wages for nearly two years, prompting them to demand pay rises to protect their living standards.

Bank of England chief economist Huw Pill sparked fury recently after he told workers to accept they’re poorer as a result of higher international energy prices.

An exodus of workers from the labour market primarily caused by a rise in long-term sickness has made it tougher for businesses to fill roles, strengthening incentives for them to hike wages to outbid rivals.

Economic inactivity – when someone is out of the job and not looking for one – has risen sharply in the UK since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, up by around 500,000.

That upsurge was initially driven by a rise in the student population, though those undergraduates are now returning the workforce to raise cash to offset rising living costs and after graduating, Goldman said.

Strong wage pressure, compounded by rising energy bills as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has forced prices much higher in the UK.

Numbers out last week from the Office for National Statistics revealed headline inflation slipped to 8.7 per cent over the year to April, down from 10.1 per cent, a much slower fall than the Bank and City expected.

Core inflation – a more accurate measure of underlying price pressures – unexpectedly rose to 6.8 per cent from 6.2 per cent, its highest level in over 30 years. Services inflation, which the Bank tracks closely to feed into its rate decisions, also jumped to 6.9 per cent.

“While the BoE has been reluctant to hike further, we believe that persistent inflationary pressures will push the MPC towards more tightening,” Goldman said.