Bank of England expected to raise interest rates by 50 points to post financial crisis high of four per cent

The Bank of England is set to hike interest rates 50 basis points to four per cent next week, jacking them up to the highest level since the financial crisis, markets expect.

City traders reckon its governor Andrew Bailey will lift borrowing costs for the tenth time in a row, something the UK central bank has not done since it was made independent in 1997 by the then Labour chancellor Gordon Brown.

However, investors think the Bank is nearing the end of its once in a generation rate hike cycle, betting that borrowing costs will peak at under 4.5 per cent.

That means next Thursday’s 50 basis point rise could be the final hike by the monetary policy committee (MPC) for some time. In fact, some think the Bank could start cutting rates at the end of the year to help the economy out of a recession.

But, there are sections of the market that think Bailey and co will nudge rates up a further 25 basis points in March.

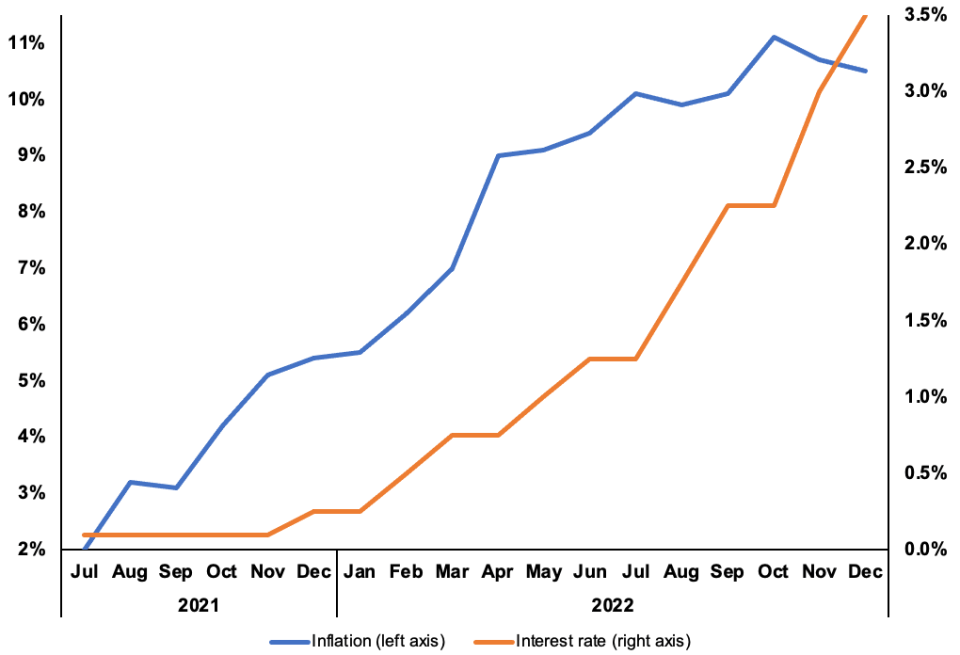

The Bank of England has been raising interest rates aggressively to tame a multi-decade high inflation surge that has ravaged household and business finances.

Experts think there is a risk inflation could stay higher over the long term unless the Bank stamps down on rapidly rising wages.

“Tightness of the labour market and the pass-through to domestic prices and wages… have been concerning,” analysts at BNP Paribas said.

Rates have risen to tame inflation

Companies are stepping up pay to lure and retain talent, while workers are demanding wage increases to protect their living standards. That has lit a rocket under private sector pay growth, which is running at seven per cent, a record, but still below inflation.

Elevated gas prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and storage issues have left energy costs more than double their low term trend.

“The UK’s somewhat unique combination of structural worker shortages, and therefore potential for persistently higher wage growth, as well as its exposure to Europe’s energy crisis, suggests the Bank of England will be less quick to cut rates than in the US,” James Smith, developed markets economist at Dutch bank ING, said.

That drop has prompted economists to predict inflation is on a downward trend this year. The Bank of England and Office for Budget Responsibility both think it will halve by the end of 2023.

Gas prices are back below their pre-Russia Ukraine war levels and shipping costs, which skyrocketed due to lockdowns snarling up trade flows, have also tumbled, both of which will push down underlying inflation and ease pressure on businesses to raise prices.

As a result, Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at consultancy Pantheon Macroeconomics, thinks the Bank will lift rates 50 basis points next Thursday and then stop.

Higher interest rates are, in theory, supposed to contain price rises by reducing incentives to spend. The Bank is trying to make it more attractive for consumers to spend and more expensive for firms to borrow.

In addition, tighter financial conditions weigh on demand in the housing market by raising mortgage rates, which can price people out of property purchases. This reduction in appetite forces sellers to cut prices, pushing average house prices lower, which makes people feel worse off, often chilling spending.

Market rate expectations have collapsed over the last couple months after they scaled to a peak of more than six per cent following Liz Truss’s calamitous mini-budget.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt reversed nearly all her £45bn of unfunded tax cuts in November and has said there is little to no room to loosen fiscal policy at the 15 March budget.

However, lower rate expectations and a faster than forecast inflation drop will hand the chancellor “something like £10bn a year” due to the amount of money the government pays investors coming in much lower than feared, Carl Emmerson, deputy director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, told City A.M.

New numbers from the Office for National Statistics this week showed borrowing hit a December record of more than £24bn, far above City forecasts, but, when measured on a nine month basis, lower than the OBR’s November projections.

The OBR has also reportedly told the treasury the UK economy will grow slower than expected over the long term, cutting Hunt’s room to maneuver.