Bank of England not to blame for looming record recession, chief economist stresses

The Bank of England is not to blame for the UK fumbling into the longest recession since records began and rate setters are not “inflation nutters,” its chief economist said today.

Huw Pill, who replaced Andy Haldane last year as Threadneedle Street’s top wonk, said the UK’s slowdown is being “driven by other forces” beyond the central bank’s rapid rate hike cycle.

“We’re trying to manage the adjustment of those other forces,” Pill added.

He added the looming recession is a “necessary part of the dis-inflation you need to see”.

Inflation soaring to a 40-year high of 10.1 per cent, coupled with weaker pay growth and higher mortgage costs, are likely to spark a spending slowdown, plunging the UK into a slow burning two year economic slump.

A large chunk of Britain’s inflation crunch has been fuelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine jolting international energy markets.

However, Liz Truss’s disastrous mini-budget on 23 September forced UK debt costs higher, which have trickled down to the real economy via higher mortgage rates.

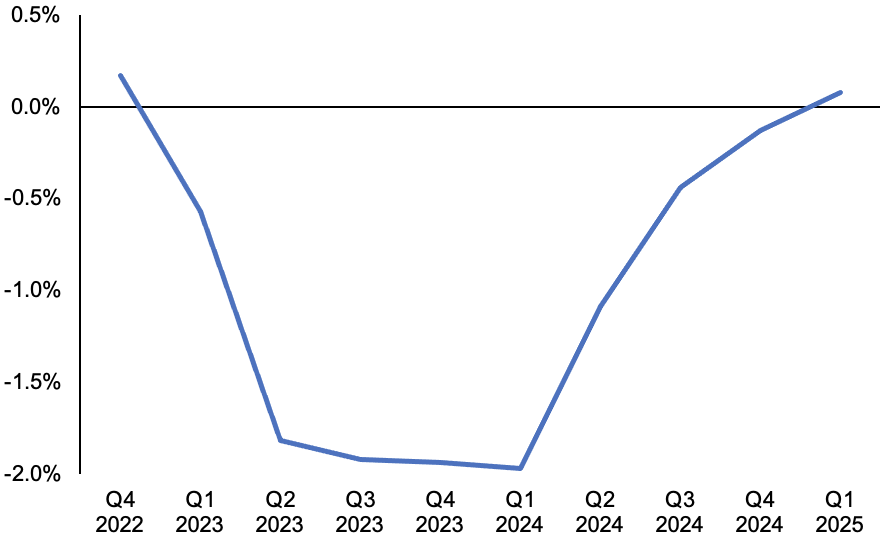

Bank of England’s bleak GDP forecasts

Economies in the eurozone are also on the verge of tipping into recession, and there are doubts over whether the US Federal Reserve can keep raising rates steeply and avoid pushing America into a slowdown.

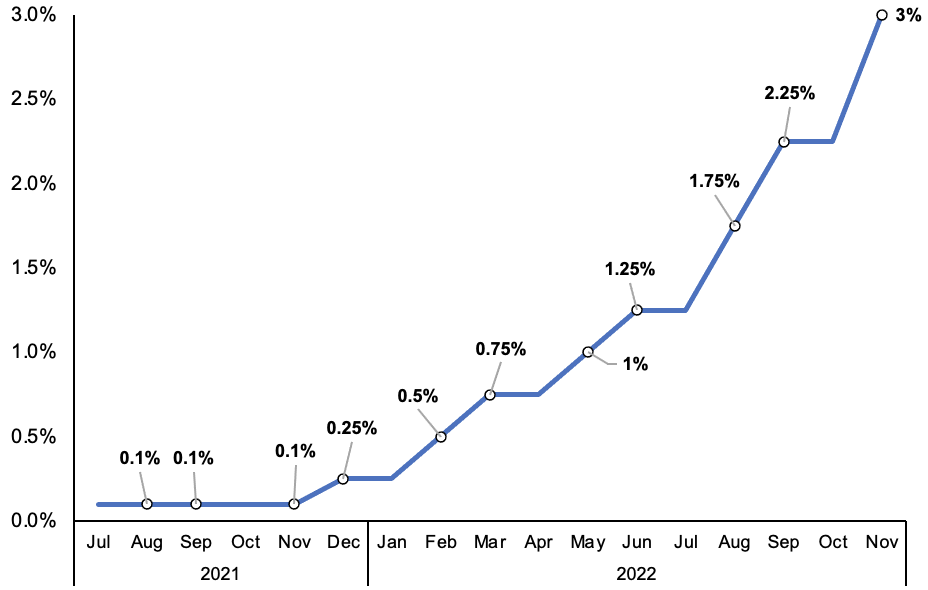

Last week, the Bank hiked interest rates 75 basis points, the biggest move in over 30 years and the eighth rise in a row, despite projecting the country will suffer eight consecutive quarters of contraction, the longest recession in around a century.

But, Threadneedle Street said the drawn out recession would only happen if borrowing costs hit 5.25 per cent, which was priced into financial markets around mid-October. Governor Andrew Bailey last week explicitly said the Bank will not lift rates that high.

Pill doubled down on those remarks today, saying the monetary authority was trying to fix a “de-anchoring” in market expectations of where rates were headed.

He also said he is “sceptical” of front-loading rate rises to get to the borrowing costs peak quicker to tame inflation, suggesting the Bank’s monetary policy committee is unlikely to keep raising borrowing costs 75 basis points.

But, Pill said the Bank will not “be moving at a pre-defined pace at every meeting,” adding the central bank “cannot declare victory against second round effects” yet.

UK interest rates have risen quickly this year

Rising prices can force household and businesses’ inflation expectations higher, prompting them to respectively demand higher wages and raise prices.

Central banks are terrified of this scenario. They typically tighten financial conditions to stop inflation embedding into an economy through so-called “second round effects”.

Pill, who voted with the 7-2 majority at last Thursday’s MPC that backed a 75 basis point rise, said higher rates are needed to prevent this “self sustaining process”.