Bank of England not poised to slash interest rates until middle of next year despite inflation cooling

A year of interest rate pain is still in store for households, businesses and mortgagors even after Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey and his team of economists have already lifted borrowing costs 10 times in a row.

That is according to several top City economists, who do not expect interest rate cuts until early next year.

Impetus on the Bank to keep piling the pressure on has receded due to inflation seemingly passing its peak of 11.1 per cent back in October.

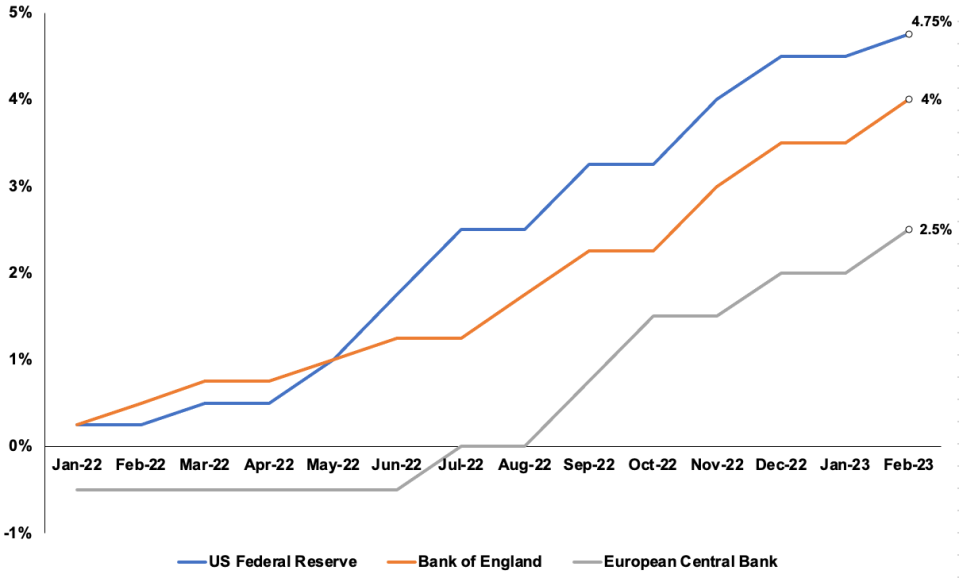

The bulk of the tightening cycle’s heavy lifting has already been done. Cumulatively rates have risen 390 basis points between December 2021 and February 2023, the fastest acceleration since the 1980s.

Doing more damage now risks making the coming recession worse than it needs to be. The Bank last week said it expects inflation to fall below its two per cent by the middle of next year if rates stay at four per cent, indicating cuts may be needed to stimulate spending.

However, the danger of inflation sticking around at a higher level due to firms passing on steep pay increases – private sector wage growth is running at record levels of just over seven per cent – means the MPC will not be coaxed into handing cash back to homeowners any time soon.

Central banks have raised rates quickly over last year

“While we expect the MPC to pause after the March meeting, the underlying message that they consider the risks to inflation to be heavily skewed to the upside reinforces our view that rate cuts are unlikely in 2023,” Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist at consultancy Oxford Economics, said.

Experts at NatWest agreed.

“We do not expect ‘early’ rate cuts (ie, in 2023) given the expected stickiness of core inflation but judge current policy settings to be restrictive (at least once full pass-through has occurred) and therefore expect policy rates to gravitate towards more neutral levels ~3.5 per cent over the course of 2024,” they said.

Concerns among the MPC about steep wage increases filtering through the economy are unlikely to abate over the next 12 months, analysts at investment bank Nomura said, adding they do not think rates will fall until mid 2024.

Bailey and co provided some good news last week. They ripped up their warning in November that the UK is on course for the longest recession in a century at six consecutive quarters.

The combined GDP hit was lifted to just under one per cent instead of the near three per cent forecast a few months ago.

Although shallower and shorter, the coming recession will result in consumers being less willing to continue to pay for goods and services after businesses have hiked prices, putting downward pressure on inflation.

Markets take a different view to the wonks. They think the Bank is poised to drop borrowing costs close to the end of this year to help lift inflation back toward two per cent and country out of recession.

A little bit of inflation is actually good for an economy. It incentivises people to spend, gives cash businesses cash to invest and lift wages and raises tax revenues for the government.

Over the past year, Britain has not had a little bit of inflation. It has had a whole lot of it.