Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey ‘very uncertain’ about inflation decline

The Bank of England’s governor, Andrew Bailey, has today admitted he is “very uncertain” about whether inflation will decline, forcing him to back another steep interest rate increase last week.

Responding to a grilling by MPs on the commons treasury select committee, Bailey, 63, said he wants to see “more evidence” of the rate of price increases falling this year before taking his foot off the brake.

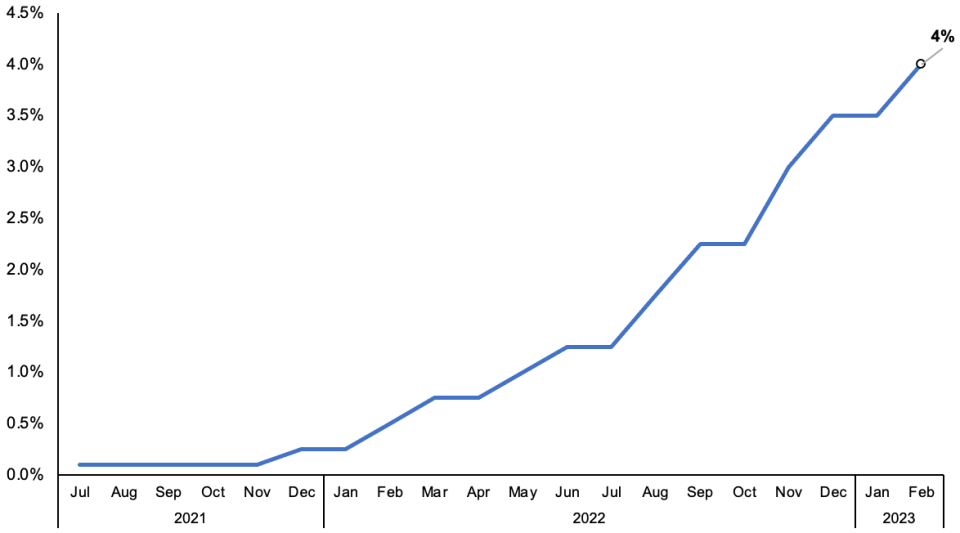

Last Thursday, Bailey voted with a 7-2 majority to raise borrowing costs 50 basis points, to a 15 year high of four per cent, the tenth rise in a row.

Several outsized hikes have punctuated that tightening cycle, which has been the sharpest since the 1980s.

Inflation raced to a 40-year high over the last year, peaking in October at 11.1 per cent. It has since dropped two months in a row for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic and the Bank of England reckons it will more than halve by the end of the year.

However, it is still projected to be more than double the Bank’s two per cent target.

Rates have risen sharply

Over the course of the pandemic and last year, the Bank consistently undershot its inflation projections, prompting Tory MP and chair of the treasury Harriett Baldwin to probe whether Bailey and co should have started lifting rates sooner than December 2021.

Bailey batted away the criticism, highlighting that Threadneedle Street was the “first major central bank to tighten” policy. The US Federal Reserve has since cumulatively raised rates more than the Bank, but did not begin listing until March 2022.

Huw Pill, the Bank’s chief economist, agreed, arguing the series of shocks that have hit the UK economy – namely the pandemic, the resulting supply chain crunch and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – mean rate setters “will fall short” of hitting their inflation target.

Pill added he is cautious of “over steering” the economy into a downturn via higher interest rates.

The country is expected to tip into a shallow recession lasting most of this year, which will put downward pressure on inflation.

The full effects of the Bank’s nearly 400 basis points of tightening has yet to spread through the economy, meaning continuing to raise interest rates could make any recession worse than it needs to be.