Bacon: Man and Beast at the Royal Academy review

The galleries of the Royal Academy are shrouded in an appropriate gloom for this Francis Bacon retrospective, the atmosphere part cathedral, part occult gathering.

Rather than simply present the works chronologically, which would have been easy given the number of paintings brought together, the RA explores Bacon’s work through a single recurring theme – his fascination with man’s bestial nature. I’ve taken exception to this approach by the RA in the past – it can feel restrictive and a little too academic – but here it serves to focus the attention towards a locomotive force that underpinned Bacon’s work from his earliest days until the very end.

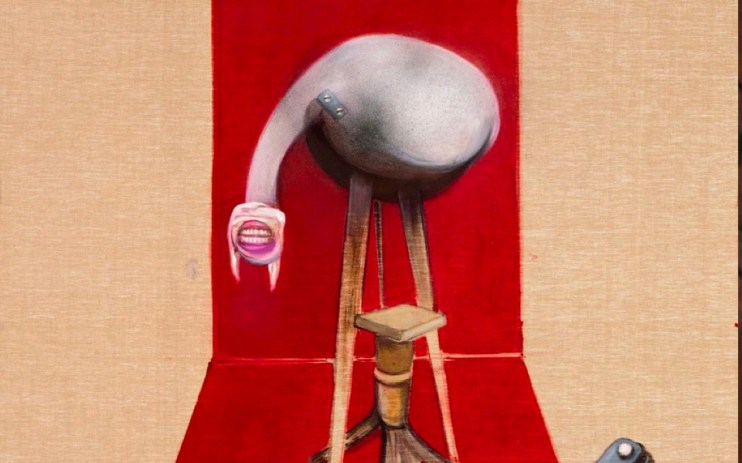

Bacon saw the essential animalness of humanity. He painted savage men bowed on all fours like sad exhibits in a zoo, men squatting on tables like apes, men howling in despair – always sealed in claustrophobic swaths of colour, unable to escape themselves.

“We are meat, we are all potential carcasses,” said Bacon, who was presumably fun at dinner parties.

Death haunts the gallery. Portraits of snazzily-clothed people show traces of bone and flesh beneath the veneer of skin. Depictions of a past lover who died of an overdose seem to dissolve, arms and legs dissipating into pink goo. A human form will be rendered in delicate, translucent brush strokes, only to be slashed with thick, bloody splodges of red oil paint. Captions on the wall have headers such as: “Flesh, skin and bone”.

To drill home the transience of it all, grotesque “furies” often appear above his subjects, mythological creatures peering down at the frail sacks of meat. No wonder Bacon is thought of as the 20th century’s preeminent nihilist.

As well as portraits of men looking like animals, there are also portraits of animals with echoes of men; mad dogs shaking feverishly in the midday sun, chimpanzees in dignified repose, owls – so many owls! – that seem to morph into apes or humans. Bacon had reference books full of ‘animals in motion’ dating back to the 19th century and would often borrow their images of ferocious jaws and ambling limbs.

It’s tempting to search for a message in all this – an animal rights leaning, perhaps. But it isn’t there – these are depictions of the grim reality of it all, a document of the “whole horror of life, of one thing living off another”.

It’s bleak, for sure, but there’s electricity here, too. This isn’t a hushed shuffle past an open casket, it’s a primal scream, the howl of an animal that’s realised its nature, the thrill of madness. Chimps scream, popes scream – he had a real thing for popes – the crowd at a bullfight screams. There’s something life affirming about the embrace of the animal, and these paintings have lost none of their potency in the 30 years since the artist’s death.