Backing the central bank pivot is a risky bet

It is easy to criticise central banks for heaping pain on households and businesses.

But, this is exactly what they are supposed to do under current economic conditions.

Inflation in the UK, US and eurozone has hit 10.1 per cent, 8.2 per cent and 9.9 per cent respectively, all historic highs.

The Bank of England (BoE and Bank), US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank (ECB) all need to keep inflation around two per cent (among other targets).

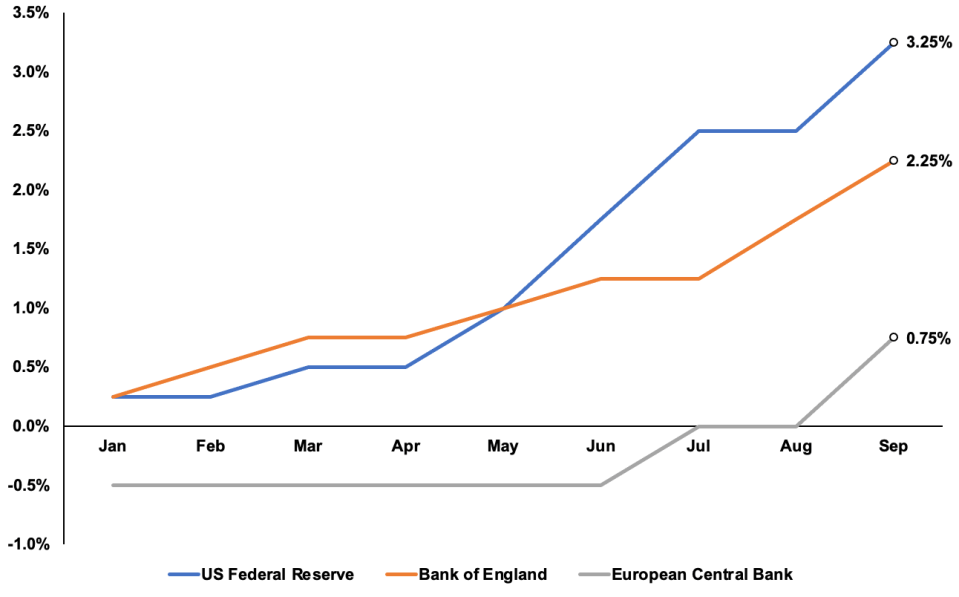

From their first hike in this current cycle, the trio have raised rates 215 basis points, 300 basis points and 125 basis points respectively.

The ECB’s cumulative hike total could hit 200 basis points tomorrow after president Christine Lagarde announces what is expected to be a second 75 basis rise in a row.

The Fed and Bank are forecast to follow that move next week.

UK, US and eurozone interest rates have risen sharply this year

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine jolting the international energy market, ongoing trade disruption as a result of the pandemic and high demand for workers rubbing against weaker supply are all to blame for this nasty price surge.

The first of that mix is by far the biggest driver. Huge gas price rises have generated what economists call a terms of trade shock for European – including the UK – countries.

This means the amount of money these countries spend on imports have soared far above the money they earn from selling their products overseas. Typically, this causes a big living standards shock and tips an economy into a sharp slowdown.

That situation is now playing out in Britain, Germany and other big European countries.

This week’s flash purchasing managers’ indexes uncovered just how poorly economies are faring. The UK’s dropped to 47.2. Germany’s is down to 44.1, both firmly in contraction territory.

The US’s PMI also dropped to 47.3. A reading below 50 indicates activity is shrinking.

So, western central banks are in a tough spot. They cannot be seen to let inflation slide. But, growth is plainly slowing and even contracting, eroding their room to keep heaping pressure on households and businesses by raising rates steeply.

Bets on Wall Street and in the City on central banks slowing the pace of rate rises have gathered pace, especially after Australia’s monetary authority delivered a shock 25 basis point rise earlier this week.

Analysts call this the monetary policy “pivot”.

The Fed’s rate hike cycle has been the fastest since the Paul Volcker days of the early 1980s.

Chair Jerome Powell and co “are likely moving too fast to fully evaluate the response of the lagged monetary policy tightening on the real economy,” Jonathan Pingle, chief US economist at UBS, told City A.M.

On the flip side, “high inflation is not good for a nation’s long term economic success”, he added.

Constantly rising prices make it tough for businesses to operate. They also erode household spending power, leading to an entrenched reduction in demand and weaker output.

Elevated prices can also raise inflation expectations, leading to workers demanding higher wages, forcing firms to keep raising prices to protect profits. This has not happened yet, with pay growth trailing far behind inflation, especially in the UK.

“The alternative of allowing inflation to stay high for a lot longer would arguably be worse and involve reduced living standards; elevated inflation also tends to hit lower income households harder than the well-off,” Anna Titareva, European economist at UBS, told City A.M.

Beyond the real economy, financial markets are reshaping as over a decade of ultra-low interest rates ends.

When such sudden shifts in economic policy cause “global financial conditions [to] tighten quickly… the possibility of “unknown unknowns”” sparking chaos rises, according to Goldman Sachs.

That has played out in the UK gilt market over the last month.

Pension funds could not withstand the shock rise in gilt yields – turbocharged by former prime minister Liz Truss’s catastrophic 23 September mini-budget – forcing the Bank to step in with a £65bn emergency bond buying package to avert a “material risk” to financial stability.

In Britain, the housing market has been identified as a potential poison for financial markets and banks, similar to the US property crash sparking the global financial crisis in 2007. The fallout would be nowhere near as large, but would certainly weigh on the UK economy.

As soon as last week, markets expected the BoE to lift borrowing costs to around six per cent.

If that happens, banks – which have already raised mortgage rates above six per cent due to the swap curve shifting upward – will have to push more misery on homeowners.

“House prices could decline by 30-40 per cent. This is not a desirable outcome for the BoE and we think acts as a ceiling on just how high UK interest rates can go,” David Storm, chief investment officer, RBC Wealth Management, told City A.M.

Bonds have suffered this year. The yield on the 10-year gilt, bund and treasury has climbed more than 230 basis points this year.

While that has made bonds relatively more attractive, it has left investors with debt holdings nursing losses. Yields and prices move inversely.

“Investors have woken to the risks of seemingly “low-risk” investments,” Thomas Gehlen, senior market strategist at Kleinwort Hambros, told City A.M.

Traders have returned to bonds after years of weak returns, weighing on stocks.

Higher yields have increased the discount rate, a tool used by investors to determine the present value of future money generated from equities. The higher the discount rate, the less attractive stocks are.

Because central banks influence the discount rate by setting base borrowing costs, they also influence stock markets.

Wall Street’s S&P 500 is down around 20 per cent this year, while the pan-European Stoxx 600 has shed around 17 per cent.

London’s FTSE 100 has lost just over five per cent, mainly due to the index being heavily geared toward old-economy stocks which have been lifted by rising energy prices.

Equities represent a big share of household wealth in the western world. Falling stock prices could deal a blow to consumer confidence.

The “rotation into high quality fixed income paying five per cent yield is interesting, in the first instance we think the bigger risk is that households use equities as a cash machine to maintain current levels of spending,” Storm added.

Ultimately, what the Fed, BoE and ECB are trying to do is weaken their economies to rebalance supply and demand.

That will mean lower stock prices, higher unemployment and, probably, recessions on each side of the Atlantic.

The eurozone, American and UK economies are already operating below potential capacity, Goldman think.

It is often hard to understand why Bank governor Andrew Bailey, Powell and Lagarde answer questions at press conferences that reveal they are damaging their respective economies.

But, when inflation is as high as it presently is, that objective is the meat of their job.

“Short term pain to reduce inflation from those heights is worth it and central bankers everywhere are telling us that they are willing to inflict pain now to ensure we do not suffer continued rounds of inflation in future,” Storm said.

Maybe don’t bet on that pivot just yet.