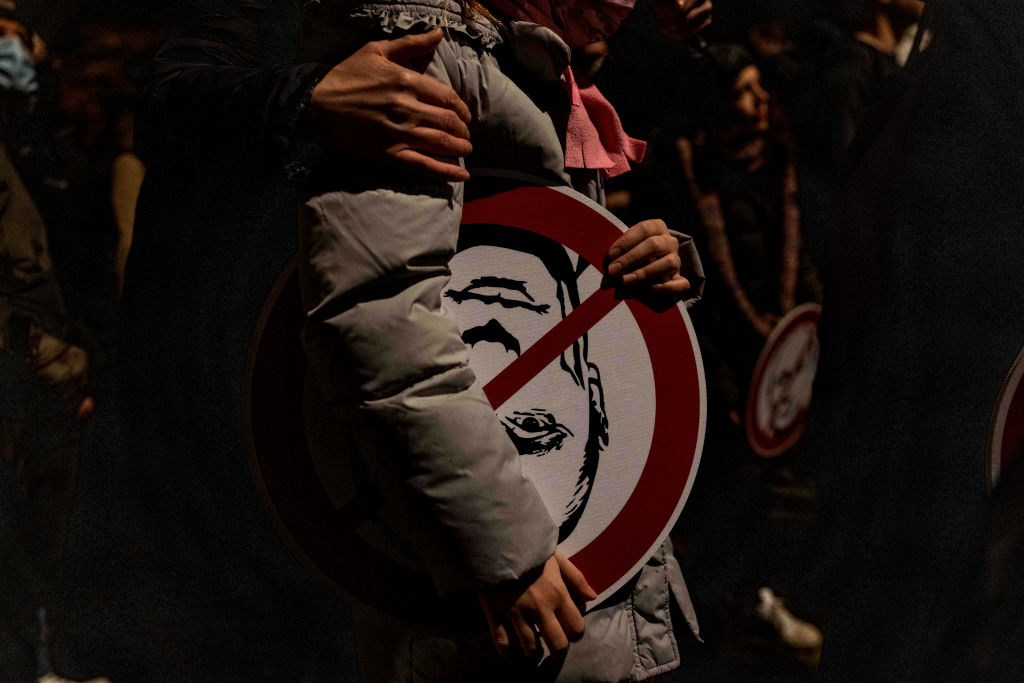

As Vladimir Putin raises the stakes, he reveals a losing hand in Russia’s war on Ukraine

Yesterday, Vladimir Putin announced his plan to formally annex four Ukrainian regions. Last week, he introduced a partial mobilisation within Russia to support the war in Ukraine.

It marks a decisive moment in his presidency and the conflict. His decision to enlist a further 300,000 troops has two profound implications.

First, he is reinforcing a losing hand in Ukraine. Second, he is definitively bringing the conflict within Russia’s borders for the first time. The combination of these two factors put his leadership on a new course – one that may lead to the very opposite of the strong, global Russia he claims to be creating. Speculation over the course of this year about his position has been premature, but in the context of the mobilisation and its impact all outcomes should now be considered possible. Ukraine and the West must call Putin’s bluff through a united position of strength.

Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine earlier this year was, as I wrote previously in this newspaper, the worst outcome for Moscow. Having failed to reach concessions through ramped up pressure on Kyiv, the ground invasion was doomed from the start. Russia did not have, and does not have, the financial capability to govern a puppet state. Now, as we have discovered, they also do not have the military capability to defeat Ukraine outright on the battlefield. From the start Putin has been playing a high stakes game of poker with a losing hand.

Earlier this summer Putin promised no mobilisation would be needed to win in Ukraine. A poor showing on the battlefield, where 50,000 Russian troops have been killed or wounded, has forced Putin to reverse his position. Russia’s first mobilisation since the Second World War has deep implications for the conflict and for Putin’s position. What the mobilisation crystallises is the fact Moscow is engaged in a conflict it cannot win, but also one that it cannot afford to lose.

Mobilisation can prolong the conflict but not decisively end it. Threats of tactical nuclear weapons, and the rushed announcements about referenda in the occupied oblasts, likewise show Putin’s desperation to change the nature of the conflict through bluster.

Public support for the war from within Russia is rapidly declining. As Russians realise that they will start to face direct consequences for the war, hundreds of thousands of men at risk of being conscripted to fight in Ukraine have headed for borders to neighbouring countries. Prices of flights to Turkey rose by 300 per cent, and a 10-mile queue formed at the Georgian border. To date, it had been Russia’s professional army fighting an initially popular war that felt far removed from most Russians. With conscription within its borders the Russian state is bringing the conflict in Eastern Ukraine to its streets at home.

While the mobilisation has so far been focussed on ethnic minorities and rural areas, metropolitan areas and elements of Putin’s core support will not be immune.

As the war drags on, particularly over the coming winter period during which professional forces are rested, the impact of the war will be felt more clearly within Russia as those conscripted hit the frontline. Putin also does not benefit from overwhelming support from pro-war nationalists, who have been disappointed by the Kremlin’s refusal to fully mobilise, and who have grown frustrated with the poor results endured on the ground. Putin in effect finds himself trapped between two opposing strands of the Russian public.

By mobilising, Putin has raised the stakes in the conflict, both at home and in Ukraine. But he is in a bind. He cannot feasibly win the war, nor can he afford to lose it.

The Russian leader faces growing opposition from the anti-war movement within Russia, but also now growing criticism from those who support the war. He is vulnerable then to those who want to end the war and those who think it could be better prosecuted, putting him in the most vulnerable position he has occupied since becoming President. Through a clear, agreed and united strategy to end the war the West finally has the chance to help Ukraine to call Putin’s bluff.

Jacob Delorme, a political researcher at the Tony Blair Institute contributed to this article