| Updated:

The art of theft: Why do thieves steal famous paintings when they’re so hard to sell?

On a freezing Stockholm evening just before Christmas 2000, a group of six to eight Middle Eastern men put into action a plan they’d been working on for months. The group parked cars in the middle of the three central roads leading to the Swedish National Museum and set them ablaze. As fire engines screeched into the city centre and passersby crowded around the spectacle, three of the men – one armed with a machine gun, the other two with pistols – approached and entered the museum on foot. After ordering everyone to lie on the floor and screaming at them to remain calm, they went upstairs to claim their prize: two small Renoirs dated around 1870 and a Rembrandt self-portrait no bigger than a postcard. The Rembrandt alone was valued at $36m. Their multimillion-dollar cargo stuffed hastily into large black duffel bags, the thieves jumped into a getaway boat and chugged away into the icy Scandinavian night.

“Criminals who steal high-value art-works tend to be better thieves than businessmen,” says Robert Wittman, former undercover agent and head of the FBI Art Crime Team. “They don’t understand that the true art in a heist isn’t the stealing, it’s the selling.” The theft at the Swedish National Museum made news all around the world, the kind of exposure that makes a sale on the legal market impossible. The black market is another story, but it can be just as difficult for criminals to make money from their loot below board. As a general rule, stolen artworks’ black-market value is around 10 per cent of the actual value, but with paintings worth tens of millions of dollars, even this mark-down is way out of most illicit buyers’ price range. “The kind of people who have the wherewithal to pay that kind of money,” says Wittman, “aren’t interested in owning something that they could never sell on and that they could possibly go to jail for possessing.”

When it comes to stealing and selling art, going cheap pays. Paintings worth in the tens of thousands are less likely to be registered on international databases and don’t make headlines when they go missing. At this price range, only about 10 per cent of stolen works are recovered. With masterpieces worth tens of millions the rate of recovery improves to around 90 per cent.

So why do criminals steal expensive art? Ever since Dr No bragged to 007 about his stolen Goya (a portrait of the Duke of Wellington), the aesthetically-inclined super-villain having priceless paintings stolen to order has loomed large in the collective imagination. In reality, no international criminal would intentionally court the attention a missing masterpiece invites.

Robert Wittman poses next to a Goya painting he helped recover

That said, it isn’t always about profit. Between 1995 and 2001, French waiter Stephane Breitwieser stole over 200 paintings and objets d’art, eventually amassing a collection worth over $1bn. After he was arrested he recalled the first painting he ever stole, a minor portrait of a woman by 18th century German painter Christian Wilhelm Dietrich: “I was fascinated by her beauty, by the qualities of the woman in the portrait and by her eyes.” Breitwieser never tried to sell the art he stole, and instead used it to decorate the home he shared with his mother, who destroyed most of it after hearing her son had fallen foul of the law.

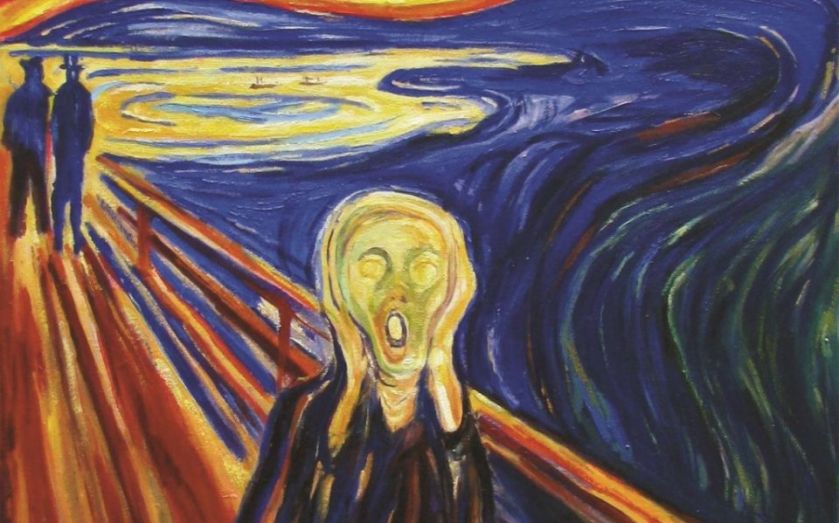

Another unusual motive lay behind the 2004 theft of Edvard Munch’s The Scream. The masterpiece, a version of which was sold at auction for $119m two years ago, was stolen from the Munch Museum by armed robbers. In the subsequent investigation detectives began to link the suspects to another armed robbery that left a senior ranking Norwegian police officer dead. In light of other peculiarities about the case (the robbers hadn’t done their homework and needed to be shown the location of the painting) officers began to suspect the work was stolen to distract police from investigating the death of the policeman; an “illustrious corpse” as the mobsters say. The criminals were right, international attention did pressurise Norwegian police into prioritising the stolen Munch. In the end, though, the painting was recovered and both thief and police killer were brought to justice.

When a painting as famous as The Scream goes missing, the authorities have no choice but to focus their attention on getting it back. But thousands of lower-value works are stolen every year, and law enforcement agencies don’t have the resources to go after them all. Scotland Yard has just three people working in its arts and antiques unit. Given that the vast majority of thefts are non-violent, and that most losses are covered by insurance, art-retrieval is largely left to the private sector. The Art Loss Register, a London-based company part owned by Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonham’s, maintains a database of over 400,000 missing works. Before each sale, dealers and auction houses have a duty to check the item against the Register. If it’s listed as lost or stolen, the ALR will then handle negotiations leading to its return in exchange for a fee.

“Often, when an item is found,” says Julian Radcliffe, founder of the ALR, “it’s owned by someone who is not the thief, but who bought it not knowing it was stolen. There has to be a private negotiation because going to the courts is too expensive.” When this happens, does the unwitting owner of the stolen work ever get to keep it? “It’s different in every country, but generally if someone has bought it in good faith, not from the thief but from someone who has bought from the thief, and they’ve held it for six years, they may have a chance of holding on to it… But if it’s a professional member of the trade [a dealer or an auction house] and they’ve not checked the Register, they won’t be able to claim good faith.”

In the world of high-value art theft, the Munch Museum heist and Stephane Breitwieser are exceptions. For organised criminals, top-dollar loot is most useful as collateral; while it may be difficult to sell masterpieces for a fat sum, information about their whereabouts can be used to leverage shorter sentences in the event the thieves find themselves facing criminal charges, whether artrelated or otherwise. Most European courts accept these kinds of plea bargains, though similar negotiations are not permitted in the US.

An art thief’s plunder, then, is most valuable to him after he’s been caught, a fact that explains the high recovery rate of high-value pieces, and why antsy thieves tend not to destroy their haul as police investigators close in.

Lucian Freud’s Woman with Eyes Closed was stolen from the Rotterdam Kunsthal

That’s not to say it never happens. On an October morning in 2012, a gang of Romanian criminals broke into the Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam and made off with seven paintings including two Monets, a Picasso and Lucian Freud’s Woman with Eyes Closed. Experts speculated that if sold legally under auction the cumulative value of the paintings would reach well into the hundreds of millions. The theft caused a media storm that spooked the gang into a hasty return to Romania, where they attempted to flog the paintings out of plastic bags for about €100,000 each. When the authorities caught wind of stray Monets being loped around the streets of Bucharest they acted swiftly – three members of the gang were arrested in January, three months after the original theft.

The authorities got their men, but they didn’t get their paintings. In the subsequent investigation, Olga Dogaru, mother of the ringleader, Radu Dogaru, confessed to burning them in a fit of panic following her son’s arrest. Like much of Breitwieser’s collection, the seven masterpieces from the Kunsthal museum met their end at the hands of an anxious mother.

This is a nightmare scenario for the likes of Wittman. Lying face down on a museum floor while thieves wave guns around is scary; for many working in the field of art crime, the prospect of a masterpiece being destroyed is scarier. How does Wittman feel when a painting is lost forever? “It’s a terrible shame because it’s a piece of genius that humanity has created. It’s a terrible loss, but even worse it’s hugely disappointing that we didn’t protect it for future generations.”

In 2005, five years after the Stockholm heist, Robert Wittman was sitting in a stuffy Danish hotel room pretending to be Mr Big. A six month investigation linking criminals in Los Angeles, Iraq, Bulgaria, Sweden and Russia had led him, finally, to Copenhagen. Opposite sat a nervous young Iraqi called Kadhum. As far as Kadhum was aware, Wittman was an American art-loving mobster, or at least someone working for the mob (when going undercover it’s best to keep things vague). An elaborate plan had been hatched by Wittman’s FBI team, trust had been won, and now it was just a question of executing the hand-over. Wittman laid out the wads of cash (the agreed sum a trifling $250,000) and in turn Kadhum handed over the Rembrandt. Wittman took it into the bathroom to take a closer look. There was no mistaking it, that golden half-smile beaming back as if to say, “thank you”. Loudly and triumphantly, Wittman uttered the code phrase: “We have a done deal.” The swat team moved in.

Kadhum was eventually sent down for two years for his part in the crime. In the five years between heist and recovery, the Rembrandt had been kept wrapped in red velvet cloth and hidden in a bedroom closet in a flat in Stockholm. No damage was sustained during its time as a hostage. The Renoirs had been recovered a couple of years earlier in a separate operation.

“Generally speaking, the groups that carry out these kind of crimes, they’re not art thieves,” says Wittman, “they’re just common criminals involved in many different criminal activities; car theft, drugs, weapons. And then one day they just happen to do an art heist.” Why? Because they see on the news when an artwork exchanges hands for $200m and their heads are turned. As long as legally sold art continues to smash records and make headlines, thieves will continue to make their own headlines with daring raids on the world’s most prestigious collections.