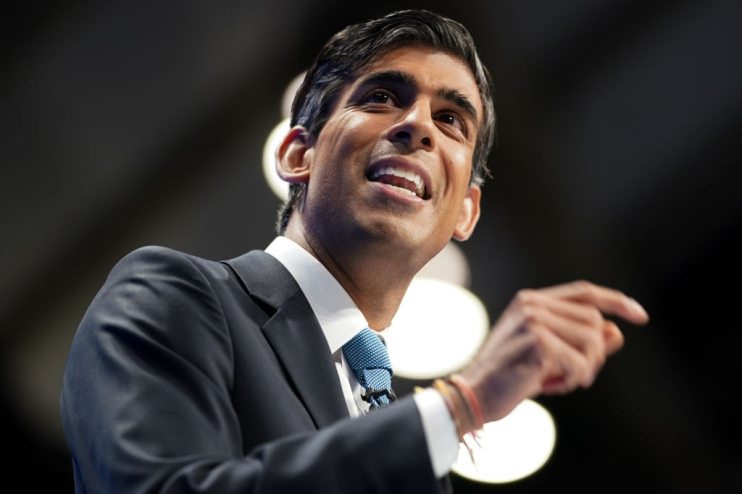

Analysis: Sunak’s wiggle room for spending in the Budget is closing in on him

Next week’s budget and spending review’s tax and spend decisions will determine the government’s economic policies for the rest of this parliament, and the amount that departments have to spend. The spending pressures on the chancellor are intense.

However, Rishi Sunak’s room for manoeuvre may well be narrowing.

Sunak has already faced down the biggest spending pressures: he has made more money available for social care by introducing a new health and social care levy and resisted pressure to retain the £20 a week universal credit uplift and to implement the exact letter of the state pension triple lock. But the chancellor still has to allocate money to public services dealing with the impacts of the pandemic. And, crucially, changes to the outlook for the economy mean that the amount of money he has available could be smaller than predicted.

In August the Institute for Government anticipated that Sunak could have £25 billion to spend; now that figure could be closer to £20 billion, and much lower if the Office for Budget Responsibility is less optimistic about economic growth than the Bank of England was two months ago.

Sunak’s fiscal windfall may not be as large as it first appeared

Back in August, a better-than-expected economic recovery had led most forecasters to upgrade their outlook since March – in particular, predicting that the pandemic would do less permanent damage to the UK economy than previously expected. We calculated that if the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) followed the Bank of England in assuming that the pandemic would only cause a permanent 1 per cent hit to the economy, rather than the 3 per cent the OBR had assumed in March, then this would mean much higher tax revenues.

In this scenario, we projected that forecast borrowing would be around £25 billion lower in 2025/26 than at the March budget.

Since then, as fears about rising inflation have taken hold, market expectations of interest rates have increased substantially. Higher interest rates are bad news for the public finances, since they increases the cost of servicing government debt. Inflation will also weaken the public finances: it means higher spending on pensions and benefits, and lower tax revenues as the thresholds at which people start paying taxes increase more quickly. Between the end of August and the close of the OBR’s forecast on 24 September, the interest rates expected in 2025/26 increased by 0.3 percentage points. This will increase projected spending in that year by £4 billion. Inflation is also now expected to be higher, increasing borrowing in 2025 by a further £1 billion.

If these were the only changes, it would mean borrowing forecast to be £20 billion lower in 2025/26 than had been expected in March if the OBR were as optimistic as the Bank. But it is very possible that the OBR will not upgrade its forecast that far. The economic outlook remains uncertain, the economic news since August has been less positive and not all forecasters expect Covid-19 to do as little damage as the Bank of England predicted. Inflation could yet be higher, interest rates could increase further, and the fiscal gain could be considerably smaller.

If the OBR were to reduce its estimate of the permanent hit from Covid-19 only marginally, from 3 per cent to 2.3 per cent, there would be no net fiscal improvement at all. The extra revenue from the slightly stronger economic outlook would be counterbalanced by the costs of higher interest rates and inflation. This would leave Sunak with no extra money to spend at all.

Sunak may have to choose between meeting his new fiscal rules and meeting spending pressures

In the March budget, Sunak made clear that his definition of fiscal responsibility meant that tax revenues should cover day-to-day spending, while borrowing for investment would be allowed. The forecast then showed that he was more or less on track for 2024/25 and 2025/26, meaning that any additional money to meet spending pressures will either need to come from an improvement to the forecast or tax rises.

A small fiscal windfall will not give the chancellor enough to meet the many demands still sitting in his in-tray. The money allocated for departments in the spending review will be very tight outside of a few protected areas like health, and addressing growing demands from demographics and the legacy of the pandemic on public services would require considerably more spending.

This will be a difficult budget for the chancellor. He has managed to avoid borrowing more in his decisions so far this autumn, but keeping to his new rules on 27 October will mean a tough spending review and little room for generous budget rabbits.