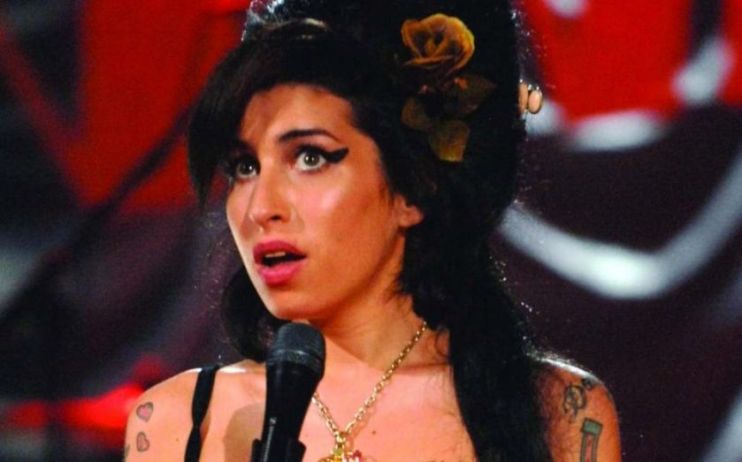

Amy Winehouse would have been 40 this year – a star remembered

The case of Amy Winehouse is so tragic that we could be forgiven for not wishing to revisit it: the druggy freneticism of her short unhappy life is something one is as much inclined to turn away from as to look at. But as a major anniversary rolls round – Winehouse would have been 40 this year, and in her prime – there is the widespread realisation that there is still a market for our morbid fascination with her unhappy fate.

In the case of the new coffee-table book Amy: In Her Words, the proceeds are going to Amy’s Place, a rehab centre which obviously does good work, according to two testimonials by addicts who have been treated there. But inevitably, given Winehouse’s short life, it is all a bit of a scraping of the barrel.

The title itself can’t help but be underwhelming. Of course, what we care about is Amy Winehouse’s life in music, and so there is an element of loss and even deflation about this project at the outset. We are reduced to her words now, when it is her voice we would love to hear.

Even so, it would be very churlish to deny that Winehouse could have a wonderful way with language. We have to remember that what we now consider the completed achievement constitutes what in another life would have been just a very promising start. Had Winehouse lived she would probably have been on her ninth album by now, and we’d know more about what she was capable of. Instead, due to her early death, we sometimes find ourselves allotting maturity to what she did, because it’s all we’ll ever have.

She was so young – and yet this book shows that a certain wisdom and self-awareness was lodged in her all along, as if in compensation for the likelihood of her early death. “Good words to describe me: loud, bold, melodramatic,” runs one entry.

But there was always something remarkable about Winehouse, which means we’ll always want to learn more. Winehouse was physically very slight, even before she became bulimic. But the voice itself could do anything: there was always something preternatural about its sheer extent and force coming out of such a vulnerable frame.

It might be that the great voices seem complete very young. Bob Dylan was a great singer by the age of 22 partly because he sounded like he had access to the wisdom of an octogenarian. The same might be said of Billie Holiday – like Winehouse, an alcoholic who died young – who sounds in a song like ‘Strange Fruit’ as though she has come into the world with an innate knowledge of how things are which would somehow not have changed had she lived to be 100.

The lyrics don’t matter all that much in Winehouse for the simple reason that the voice is so good that it obliterates all before it. However, she did have a verve with language which shows that she had been paying attention to the linguistic possibilities showcased in Britpop, especially in bands like Blur and Pulp. The content of the lyrics can be dark and depressing since they reflect a life which we wish had been otherwise, but songs like ‘Rehab’, ‘You Know I’m No Good’ and ‘Back to Black’ all have spirited lyrics which mean we can’t dismiss out of hand the notion of a collection of her words.

Nevertheless, there is a caveat. In those three songs I have mentioned, there are two depressing factors. The first is her self-loathing, leading to an apparently logical insistence on the continuation of drug abuse. It is impossible to listen to ‘Rehab’ without thinking the singer has got the matter precisely wrong and that rehab is really the best place for her. It’s a magnificent track, but in the line about her preferring to listen to Ray Charles than to go to rehab, one wants to be pedantic and remind her that she could just as easily listen to Ray Charles in rehab: if she’d done that she’d still be around today. “Beyoncé and pathos are strangers. Amy Winehouse and pathos are flatmates, and you should see the kitchen,” as the great Clive James put it.

The second unfortunate aspect of the words is the description of her relationship with Blake Fielder-Civil who is by any standards one of the least appealing plus ones in the history of popular music. Phenomenally vain, there remains the sense that Fielder-Civil took Winehouse for granted, using her as a sort of bank for drug money and not minding about the effect their shared addictions had on her. In the documentary Amy, he sometimes seems to be acting the pantomime villain, until one realises that he really is this way – assuming the complicity of the viewer out of a pure ignorance and arrogance which stood out even in that pointlessly hedonistic decade the so-called Noughties.

This is what injures these songs from the lyrical perspective and marks out their immaturity: the subject of the song seems so plainly overvalued that we wonder about the validity of Winehouse’s overall perception of life. The scene in Jamaica and Spain in ‘You Know I’m No Good’ for example can in no way have been a ‘sweet reunion’, since it unfortunately was a reunion with Blake. One can sense through the misguided protestations of the lyric that his interest in her carpet burn is transactional and that the singer has fatally misjudged everything about the situation.

Perhaps we simply know too much about her life. We know nothing of Shakespeare’s life, and it may be that the Dark Lady treated the playwright as badly as Fielder-Civil treated Winehouse. But sometimes it helps not to know, and there must be few Winehouse fans who delight in the notion of Fielder-Civil. We wish she were singing about someone else, but she’s always singing about him.

Even so, this book reminds us that she could be very funny. There is a brief journal entry berating herself for her eating habits: “No fucking carbs, bitch.” There is also an amusing story in this book of Winehouse in court. When accused wrongly of assaulting a dancer, she showed a leg to the judge and said: “Could someone with feet this small be intimidating?” But every page of sweet drawings, or little notes to self, all of which tapers off by the release of her first album Frank in 2003, is full of an understandable yearning on the part of her bereaved parents who have compiled the book that she were still here.

This is a book then about the girlhood of someone who dramatically lost all sense of innocence very quickly due to excessive drug and alcohol intake. Why does addiction lead to a loss of innocence, which is really a loss of self? It’s because we cease to dream and wonder which is what children do; instead we’re caught in a loop, unable to look ahead and no longer open to enchantment about what life may yet contain.

The fact that we wish it could all have been so different for Amy Winehouse can make us forget that sometimes, in precious instances, it was. That was when she was sober in the vocal booth – and then she showed herself to be one of the great singers of any era.

In certain instances, we talk of God-given talent and sometimes what we are noticing is a huge juxtaposition between a person’s daily life and what, all of a sudden, they can be capable of. The classic example of this is Mozart, though his life has been somewhat Hollywoodised by the Peter Schaffer film Amadeus (1984). It is impossible to shake the sense that something wonderful was bestowed on Winehouse – a complete musical soul which in a remarkably short space of time rushed to maturity, en route to its own destruction.

The great example of this is her rendition of ‘Valerie’, her version of the Mark Ronson song which had originally appeared on the 2006 Zutons album Tired of Hanging Around. Here, Winehouse shows us what she might have been capable of had she lived: there would have been extensive proof across a large catalogue that she had few obvious peers in the interpretation of song.

It’s worth remembering that ‘Valerie’ was initially written from the male perspective and so there’s something inherently fun and joyous about Winehouse singing it; the song acquires a certain Sapphic feel just by virtue of her doing it at all. This is important because too many cover versions lack a decent reason for their existence: one needs to know why one isn’t singing a new song, but redoing an old one. Winehouse knew that by taking on this track she would shine a new light on it.

I am especially fond of the song because, written in 2006, it can transport us back in time to an era just before the widespread adoption of the mobile phone and WhatsApp. The Internet had been invented, yes, but we were still communicating over written email. In this song, the singer – Ronson/Winehouse – goes to the US and meets a vivacious ginger-haired girl who he falls for. He returns to the UK – the song is actually based in Liverpool – and looking out over the sea which separates them, thinks back on his time with her and asks her questions about how she is, whether she’s changed the colour of her hair, and whether she’s got over her legal problems. Today, we’d be in contact, sending photographs of ourselves across the Atlantic.

The song is fixed in a moment in time when that wasn’t possible, and the heart would ache imagining what someone who we’d left for good was doing. The way Winehouse sings the word ‘hair’ – ‘did you change the colour of your hair?’ – in the first verse is sublime, doting on the physical detail she loved about the vanished girl, but playfully too as if the primary emotion of recollecting her is joy in spite of absence. The same trick is then repeated on the word ‘lawyer’ on verse two – its light-heartedness suggests the girl’s troubles are already surmounted, if only because she’s singing this song to her on the other side of the world.

The song makes you think of a certain togetherness which the imagination could create when it sought to overcome distance; by association it makes us think of the secret distances between us in the interconnected world we now have.

It is the good nature of the song and the generosity of Winehouse’s performance which marks ‘Valerie’ out and makes us mourn her all the more. Most songs written by men who have been separated from their women take a jealous turn: the song will usually say something to the effect of: “I bet you’re with some other man and I’m jealous enough to write this song about my predicament.”

Such songs reflect how many people feel, but they’re essentially selfish. ‘Valerie’ isn’t like that at all: it roots for the girl no matter what she’s doing. It wants her well-being and her friendship come what may. It’s an extremely good song, but it took Winehouse to turn into a great record.

In wishing she had lived longer, we can forget that she lived at all – and that we wouldn’t wish for more if she hadn’t hit such heights. ‘Valerie’, most of Back to Black, some of Frank, the incredible skirling vocal in the bridge to her cover of Carol King’s ‘Will You Love me Tomorrow?’ – most of us have outlived Winehouse by many years and never found such glory within ourselves.

In the end, the attempt to resurrect Winehouse in this book, and in the upcoming film Back to Black starring Marisa Abela, bump up against the fact that she resurrects herself every day the world over on iTunes and Spotify. That’s the good news about her: the music is where her life always was, and where it will always be.