Amazon’s ebbs and flows

The dotcom giant is at the forefront of growth in the online retail industry. Its sales have just kept on growing, hitting $1bn in America and Canada. But yet its share price has taken a tumble this week.

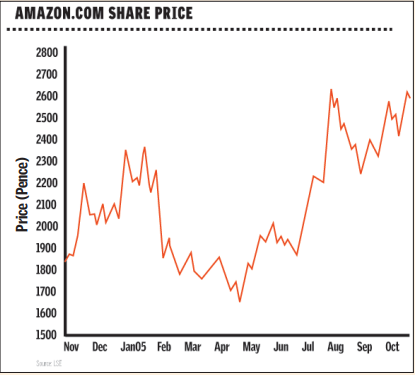

Wall Street is always falling in and out of love with Amazon. In the online retailer’s 10-year history its shares have veered from lows of $3 (£1.69) in 1997 to $120 in the heady dotcom days of 1999.

This week, it was the company’s turn to get dumped like an unwanted lover as brokers responded to third-quarter figures.

Its shares fell by 8 per cent amid concerns over trading in the all-important run up to Christmas, despite the best efforts of founder and CEO Jeff Bezos to talk up prospects for the next three months.

What happens next to Amazon is going to be one of the most closely watched events by those with a vested interest in judging the state of consumer confidence.

Amazon is a huge force in online retailing and is the bellwether of internet commerce with the accompanying dizzying history of ups and downs. It not only shifts a huge amount of books — it pre-sold 1.6m copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince this year — it is now making waves in the sales of electronics and general merchandise with $2bn (£1.1bn) of revenue in 2005.

Harry and the vanishing profits

So why did its shares fall this week? Unfortunately for Amazon, a much less well-known company from Chicago managed to dent profits by $20m. Soverain Software forced Seattle-based Amazon, which is valued at $19bn, to eat humble pie after an 18-month dispute over a patent. Soverain filed a lawsuit in Texas alleging that its copyright in a web-based payment system had been infringed, as well as in an interactive virtual shopping cart.

In August Amazon decided to cut its legal costs and settle the claim, agreeing to pay $40m, which after costs hit profits in the third quarter by $20m.

Without admitting wrongdoing, the dispute resulted in profits being torn almost in half, down to $30m from $50m.

However, Wall Street was more concerned with fundamental trading conditions, which sent the shares down to $46.17.

The retailer has been discounting deeply on items such as books and electronics amid intense competition from rival retailers for products that can be bought online as well as in stores. A classic example is Harry Potter. Like one of the magical feats in the book, the company managed to sell 1.6m copies — but it made hardly any profit. Most of the books were sold in advance in the company’s largest new product release, but not many were sold after the release, despite reduced prices.

Cloudy sales forecasts

Wall Street has also been made a little seasick by progress in Amazon’s free shipping promotions. It is offering customers a deal in which they can get unlimited two-day shipping on all orders for $79 a year. For an additional $3.99 an item the product can be shipped overnight.

The programme has come at a cost, however. It has managed to earn $112m in the last three months, which is 30 per cent more than in 2004. The problem is that losses on the service have gone in the opposite direction, having increased 15 per cent to $47m.

In Britain the company is now offering free shipping on orders of more than £15 whereas in the past shipping was free for orders of more than £19.

Of even more concern is what analysts are calling “conservative profit projections” for the rest of the year. The company was not delivering an assessment for 2006, but it said operating income was expected to be between $403m and $478m for 2005. That means either a 9 per cent decline or an 8 per cent rise depending on the actual outcome. A lower sales forecast than previously anticipated combined with the 44 per cent profit drop in the third quarter spooked the market.

Nevertheless, shares in the company were not battered. The company’s stock has been as low as $31 this year. They began the year at around $35 and are now worth $10 more.

Part of the strength is coming from a general sentiment that online retailing is growing at a healthy rate.

Just last week, IMRG, the global trade body for online retailers, said growth in September’s online retail was double that at the beginning of 2005 as millions of consumers “continued to shun the high street”.

That is down in part to price-cutting and free transportation on many occasions. Amazon has been at the forefront of growth and can take the credit for opening the door to millions of customers who chose to buy on line for the first time.

However, in some quarters it is accused of damaging the market.

James Roper, the chief executive of IMRG, said: “Amazon’s land grab of internet trade is at an awful cost. “The company has been building the brand for years with a single aggressive purpose of market share.

“It is buying the market with wafer thin margins and this is inflicting a terrible cost on the whole retail industry. “Old trading methods are being used on the internet and it is inappropriate. Now they are bearing some of the cost themselves of their margins.”

Roper pointed out that Amazon was not one of the trade body’s members. That is viewed by some as an example of the company’s desire to remain aloof.

Roper continued: “The real problem that the industry has is that the market has become unhealthily competitive. It needs to remove the unhelpful margins.”

This, he says, has bad implications for customer service and even for jobs.

Christmas cheer

Amazon is certainly managing to pile on the sales if not the profits around the world, according to its latest figures.

In America and Canada, it sold just over $1bn, up 28 per cent from the same time last year. It declines to disclose sales in other regions country by country but it says that Britain’s amazon.co.uk and sites in Germany, France, Japan and China made sales of $817m, up 26 per cent, despite a hiccup caused by international exchange rates.

In Britain, the company’s acting managing director, Ryan Regan, said that sales of general merchandise would lead to the best Christmas ever. “Some of the drivers of the top-line growth are the investments we are making in lower prices to our customers.”

He said the company was very happy with the investment it was making in free shipping.

“We think it is the right thing to do for customers and the experience to date has been that they recognise the value and buy more with us.

“We are excited about the Christmas period. We think we are going to have our biggest Christmas ever. On the electronic side, products we think are going hot are iPods and the digital SLR cameras.”

Will there be a Christmas celebration globally for Amazon staff? “I am afraid we do not disclose that kind of information,” said Regan.

Books that kept on delivering

Jeff Bezos the Amazon founder, began looking for ways to make money on the internet in 1994.

The Texas-born entrepreneur had worked on Wall Street developing computer systems before he moved to a hedge fund in the early 1990s. He quit in 1994 when he discovered the worldwide web — and with a $300,000 loan he set up Amazon.

Bezos had spotted an opportunity to sell products to a wider market at a lower cost than in traditional shops and decided on books because they were easy to deliver via the post. On 16 July 1995, Amazon.com was launched as the world’s biggest book store.

Bezos originally wanted to call the company Cadabra, as in Abracadabra, but was talked out of it by a friend. He plumped for the name Amazon because it is the world’s largest river, and his ambitions for the company were large. Sales grew rapidly from the start, but like almost all dotcom firms, so did the losses.

The turning point in the company’s fortunes came in May 1997. It became a public company and went on to launch the British Amazon site the following year — just in time to catch the dotcom boom.

In 2000, Amazon survived the crash and expanded into new markets. It now sells everything from gardening tools to iPods.