After four holds in a row, when will the Bank of England cut interest rates?

The Bank of England closed the door on raising interest rates any further today, but the central bank did not quite go so far as to suggest interest rates will be cut in the immediate future.

Its decision to leave rates on hold for the fourth consecutive meeting raises the obvious question: when will interest rates start being cut?

Policymakers did not answer this question directly, but they did give some clues as to the factors at play.

On the one hand, Andrew Bailey noted the significant progress on inflation since the last Monetary Policy Report (MPR) in November. Inflation currently stands at four per cent, lower than the 4.6 per cent expected by the Bank.

On the other hand, a number of indicators of domestic pressures – such as wage growth and services inflation – remain too high to be confident that inflation is falling to two per cent sustainably.

“Things are moving in the right direction,” he said. “But we have to be more confident that inflation will fall all the way to the two per cent target and stay there”.

Staying at two per cent is the crucial problem for the Bank.

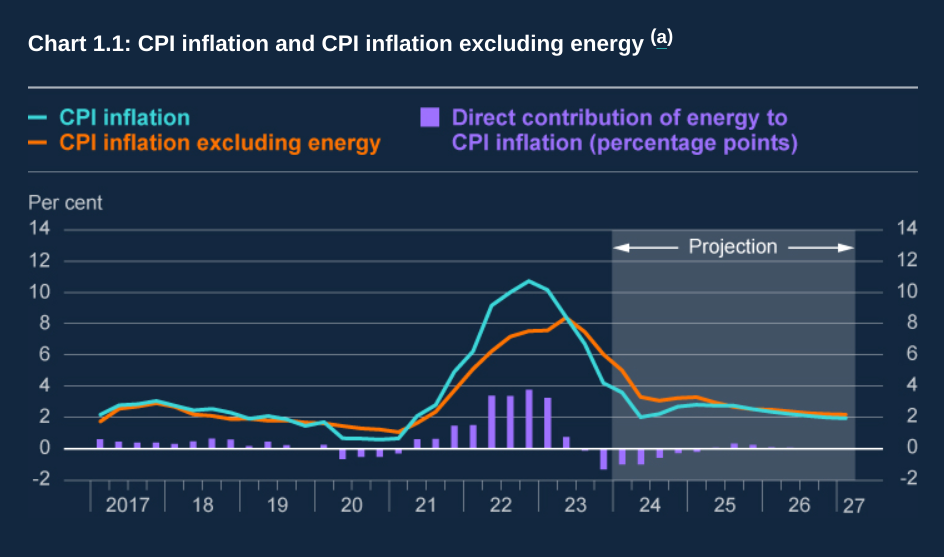

Its latest round of forecasts, released today, suggest that inflation will brush two per cent in the second quarter, before picking up again in the second half of the year.

The sharp fall in headline inflation over the past few months reflects the steep fall in energy prices. This is expected to continue in the coming months, bringing inflation down to two per cent.

But as the downward impact of falling energy prices lessens, underlying inflation will prove to be relatively stubborn.

Its important to note that the uptick expected later this year is not a major resurgence, but the Bank’s caution on cutting rates reflects concerns that inflation could become embedded above the two per cent target.

“It is not as simple as inflation falling to target in the spring and the job being done,” he said.

However, Bailey did say the framework for decision-making had changed. “The key question has moved from how restrictive does policy need to be, to how long do (interest rates) need to be at this level,” he said.

So what would it take for the Bank to start lowering rates?

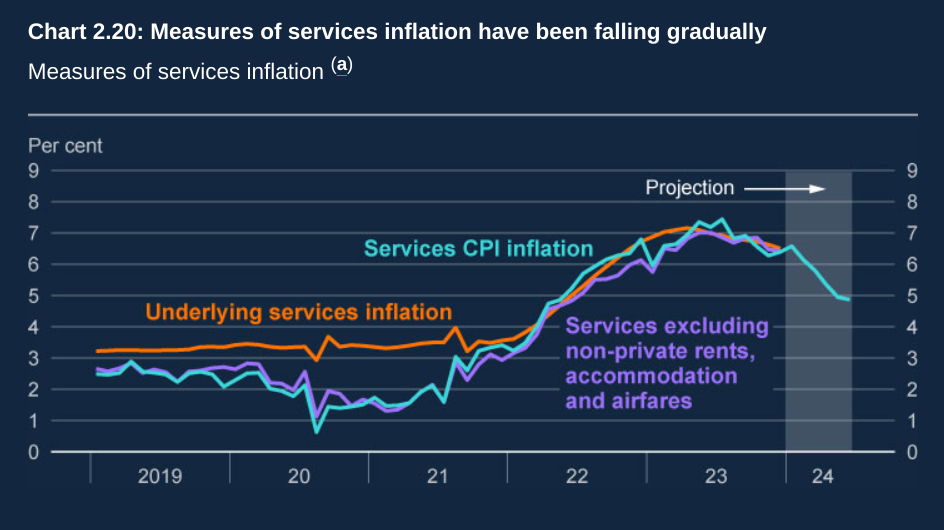

In short the Bank is looking to see greater progress on its key measures of domestic inflation – wage growth and services inflation. Inflation can be harder to quash when its driven domestically, hence the Bank’s concern.

Having started to fall gradually over the past few months, services inflation stands at 6.4 per cent. Bailey warned that services inflation “tends to be persistent”.

How do you get services inflation down? The MPR suggests that “moderation in pay pressures is likely to be required for services inflation to return to target consistent rates”.

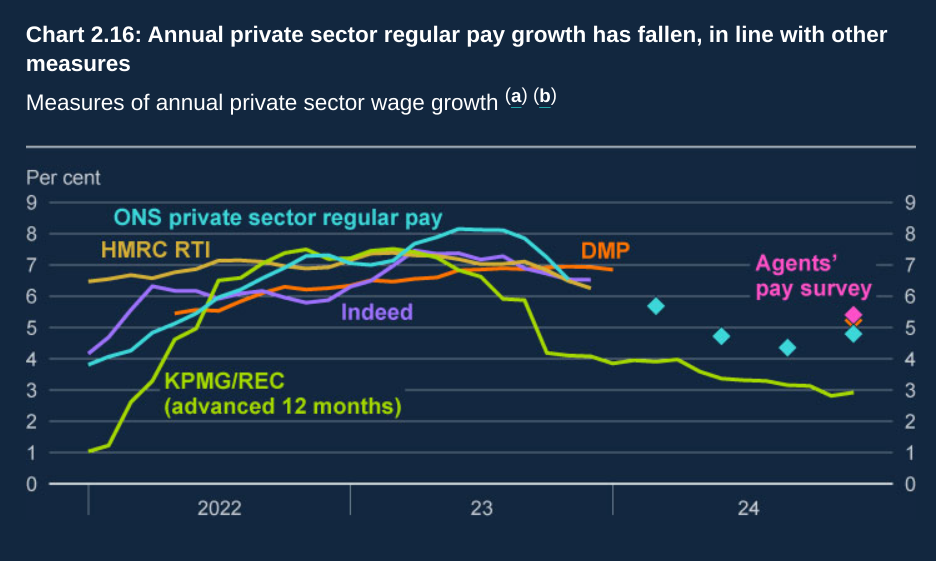

The good news is that, like services inflation, pay growth is also starting to slow. The most recent figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) put annual wage growth at 6.6 per cent, down from a peak of 8.5 per cent last summer.

The bad news is that this is still some way off being consistent with the Bank’s two per cent inflation target, while the forecasts also flagged potential factors which could lead to higher wage growth.

The Bank’s own surveys suggest that pay will only moderate “only slightly” in 2024. It also acknowledged the possible effect of the increase in the National Living Wage, which comes into force in April.

However, the impact of the Living Wage is likely to be fairly small. “The relatively low level of coverage, the low rate of pay compared to average wages, and the fact that employers are likely to have implemented pay increases independent of the NLW, all reduce the direct impact on aggregate pay,” it said.

Looking at the Bank’s key indicators, the message seems to be that the UK is moving in the right direction, but we are not quite there yet. Come summer though and it’ll likely be a different story.